Influence of Initial Provider on Health Care

Utilization in Patients Seeking Care for Neck PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017 (Oct 19); 1 (3): 226–233 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Maggie E. Horn, DPT, PhD, MPH, Steven Z. George, PT, PhD, and Julie M. Fritz, PT, PhD

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery,

Physical Therapy Division,

Duke University, Durham, NC.

OBJECTIVE: To examine patients seeking care for neck pain to determine associations between the type of provider initially consulted and 1–year health care utilization.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: A retrospective cohort of 1702 patients (69.25% women, average age, 45.32±14.75 years) with a new episode of neck pain who consulted a primary care provider, physical therapist (PT), chiropractor (DC), or specialist from January 1, 2012, to June 30, 2013, was analyzed. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each group, and subsequent 1–year health care utilization of imaging, opioids, surgery, and injections was compared between groups.

RESULTS: Compared with initial primary care provider consultation, patients consulting with a DC or PT had decreased odds of being prescribed opioids within 1 year from the index visit (DC: adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.54; 95% CI, 0.39–0.76; PT: aOR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.44–0.78). Patients consulting with a DC additionally demonstrated decreased odds of advanced imaging (aOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.15–0.76) and injections (aOR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19–0.56). Initiating care with a specialist or PT increased the odds of advanced imaging (specialist: aOR, 2.96; 95% CI, 2.01–4.38; PT: aOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.01–2.46), but only initiating care with a specialist increased the odds of injections (aOR, 3.21; 95% CI, 2.31–4.47).

There are more articles like this @ our:

Chronic Neck Pain and Chiropractic PageCONCLUSION: Initially consulting with a nonpharmacological provider may decrease opioid exposure (PT and DC) over the next year and also decrease advanced imaging and injections (DC only). These data provide an initial indication of how following recent practice guidelines may influence health care utilization in patients with a new episode of neck pain.

KEYWORDS: ACP, American College of Physicians; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DC, chiropractor; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; IQR, interquartile range; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCP, primary care provider; PT, physical therapist; UUHP, University of Utah Health Plans; aOR, adjusted odds ratio

From the Full-Text Article:

Background

The social and economic burdens of neck pain are immense, and neck pain is regarded as a major public health problem. [1] Approximately half of all individuals will experience a clinically important neck pain episode over the course of their lifetime. [1] Although 80% of people with neck pain eventually seek care, [2] there is no consensus regarding the optimal provider to begin an episode of care. Research supports that the health care system entry point (ie, the type of provider a patient sees first) for an episode of low back pain affects downstream health care utilization. [3, 4] However, in patients with neck pain, there is little information on the influence of entry point into the health care system on downstream health care utilization.

Many of the recommendations for the management of patients with neck pain have been extrapolated from the low back pain literature, [5] yet little is known about how these recommendations influence outcomes for patients with neck pain. Current recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [6] and the American College of Physicians (ACP) [7, 8] in patients with low back pain favor nonpharmacological management as front-line treatment. Although most patients initially consult with a primary care provider (PCP) for a new episode of neck pain, patients also consult with chiropractors (DCs), [9] physical therapists (PTs), [10] and medical specialists such as physiatrists [11] and neurologists. [2] Accordingly, it is imperative to evaluate the difference in health care process and outcomes in patients initially consulting with nonpharmacological providers (ie, DCs and PTs) and pharmacological providers (ie, specialists) in comparison to PCPs, who are the providers traditionally consulted for a new episode of neck pain. Evaluating the health care processes and outcomes in front-line providers for neck pain will provide support for management pathways and care consistent with recent guidelines.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine a cohort of patients seeking care for a new episode of neck pain to determine the associations between the type of initial health care provider consulted and 1–year neck pain–related health care utilization.

Patients and Methods

Patients consulting a health care provider for a primary complaint of neck pain from January 1, 2012, to June 30, 2013, who were insured under one plan, University of Utah Health Plans (UUHP), were included in the analysis. Patients insured under the UUHP were participating in either a Medicaid capitated plan or a private, employer-based plan. Patients sought care from hospital-based or ambulatory outpatient clinics in Salt Lake City and surrounding coverage areas. This study was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

We identified patients with a new consultation with a health care provider for a primary or secondary diagnosis of neck pain using claims data on the basis of the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes: 721.0, 721.1, 722.0, 722.4, 722.71, 722.81, 722.91, 723.0–723.9, 739.0, 739.1, and 847.0. We defined the date of the first consultation with a health care provider with a neck pain ICD-9 code as the index visit. We included patients with a diagnosis of neck pain for which a patient had not sought care in the past 90 days. Therefore, we excluded any patients who had a neck pain ICD-9 code associated with any claim in the preceding 90 days. The 90–day washout period was chosen to provide adequate time to reflect a pain-free state while acknowledging the biases associated with a washout period less than 1 year. [12]

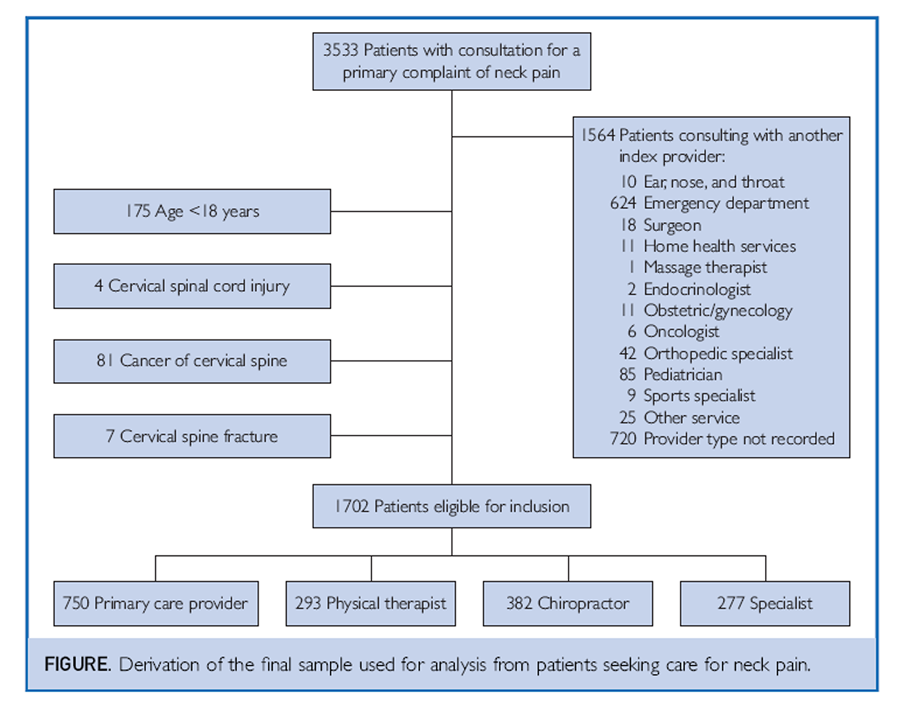

Figure From the sample of patients consulting a health care provider for a new episode of neck pain, we categorized the initial provider consulted on the index visit as

(1) PCP (including family medicine, internal medicine, or advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants working in primary care settings),

(2) PT,

(3) DC, or

(4) medical specialist (including neurologists and physiatrists).These specific provider types were included in the analysis because they are the most common providers consulted for neck pain. [3] Visits to these providers were covered under the terms of UUHP policies (Medicaid capitated plan and the private, employer-based plan) without prior referral from a PCP or insurance preauthorization. Index visits with other providers were excluded, as were visits for which there were missing data on the provider type. We further excluded patients younger than 18 years and patients with diagnoses that may require utilization of specific procedures after the initial visit including a cervical vertebral fracture, cervical spinal cord injury, or malignant neoplasm (Figure). We were unable to measure prior opioid exposure, severity of symptoms, patient-reported outcomes, or patient factors related to accessing providers within the data set.

Comorbidities

Table 1 We identified comorbidities that may influence neck pain prognosis or health care–seeking behaviors from recorded ICD-9 codes in the claims data in a 1–year period following the index date. We recorded the following comorbidities: low back pain, [13] fibromyalgia, [14] chronic or generalized pain, [15] substance abuse, depression, anxiety, tobacco use, and obesity. See Table 1 for specific ICD-9 codes used to identify each comorbidity.

Outcome Variables

We identified health care utilization outcomes from billed procedure codes for a 1–year period after the index visit for neck pain. We identified surgical procedures performed in the cervical spine (spinal arthrodesis, discectomy, laminectomy, or fusion); injections in the cervical spine or nerve blocks; advanced imaging of the cervical spine via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography, and radiography; and prescription of an opioid within 14 days, 30 days, or 1 year after the index visit.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC). Baseline characteristics and health care utilization variables were compared between index providers using 1–way analyses of variance for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. When comparing the duration of the episode of care, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used because of violations of assumptions of normality. [16]

Logistic regression compared odds of subsequent health care utilization of injections, imaging (MRI or radiography), and prescription of opioids (within 14 days, 30 days, or 1 year from the index visit) between index visit providers. Based on previous literature, the covariates of age, [17] sex, [17] comorbid low back pain, [4] comorbid depression and anxiety, [18] comorbid chronic pain, [2] and comorbid fibromyalgia were included in each model as well as health insurance plan type.

Results

A total of 3533 insured patients sought care for neck pain under the UUHP from January 1, 2012, to June 30, 2013. Of these patients, 1969 patients sought care from a PCP, PT, DC, or specialist. After exclusion criteria were applied, 1,702 patients (86.40%) were included in the analyses. Most patients in the sample were women (1,179; 69.25%), and the average age was 45.32±14.75 years. Altogether, 665 (39.07%) of the sample was insured by private insurance and 1,037 (60.93%) were insured under Medicaid. The most common initial provider type was a PCP (n=750 [44.07%]), followed by DC (n=382 [22.44%]), PT (n=293 [17.22%]), and specialist (n=277 [16.27%]). Patients seeking care from a DC or PT had the lowest prevalence of chronic or generalized pain (9 [2.36%] and 58 [19.80%], respectively), substance abuse (16 [4.19%] and 36 [12.29%], respectively), depression (63 [16.49%] and 85 [29.01%], respectively), anxiety (61 [15.97%] and 61 [25.94%], respectively), and tobacco use (23 [6.02%] and 36 [12.29], respectively). In contrast, specialists had the highest prevalence of patients with any comorbidity, with the exception of low back pain, for which DCs had the highest prevalence, (292 [76.44%]). Groups did not differ in the prevalence of obesity.

The median duration of an episode of care in the sample was 42 days (interquartile range [IQR], 1–239). Initial provider groups significantly differed in the duration of an episode of care, with patients seeking care from a PCP having the shortest median episode of care (1 day; IQR, 1–150) followed by PT (51 days; IQR, 20–209), specialist (91 days; IQR, 1–275), and DC (120 days; IQR, 12–295) (P<.001).

Health Care Utilization

Table 2

page 5

Table 3 Surgical Procedures The occurrence of cervical spine surgery was rare in this sample, with only 1.12% (19 of 1702) of the patients undergoing surgery (Table 2). Subsequent adjusted comparisons of utilization of surgical procedures could not be performed because of low frequency. In unadjusted comparisons, patients who initially consulted a specialist most frequently underwent surgery (4.69%, 13 of 277 patients), followed by PCP (0.53%, 4 of 750 patients), PT (0.68%, 2 of 293 patients), and no patient seeking care from a DC underwent cervical spine surgery

Prescription of Opioids We examined the odds of being prescribed an opioid within 14 days, within 30 days, or within the 1–year period from the index date (Table 3). The odds of being prescribed opioids within 14 days was not reduced when a patient initially consulted with a DC or PT (DC: adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.79; 95% CI, 0.53–1.18; PT: aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.55–1.02) but was increased if a patient initially consulted with a specialist (aOR, 3.24; 95% CI, 2.33–4.50). The odds of being prescribed opioids within 30 days was reduced if a patient initially consulted with a DC (aOR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39–0.81) or PT (aOR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51–0.91) and within the 1–year period from the index visit (DC: aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.39–0.76; PT: aOR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.44–0.78) compared with initial consultation with a PCP. For patients who initially consulted with a specialist, the odds of being prescribed opioids did not differ from patients consulting with a PCP within 30 days (aOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.69–1.23) or within a 1–year period from the index visit (aOR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.87–1.63).

Injections Compared with initial consultation with a PCP, the adjusted odds of receiving an injection in the following year was increased if the initial consultation was with a specialist (aOR, 3.21; 95% CI, 2.31–4.47). If a patient sought care from a DC, the odds of receiving an injection were reduced (aOR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19–0.56). There was no difference in the odds of receiving an injection if a patient sought care from a PT (aOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.99–2.07).

Advanced Imaging and Radiography Compared with initial consultation with a PCP, the adjusted odds of undergoing advanced imaging (MRI or computed tomography) within the 1 year from the index visit was reduced when the initial provider was a DC (aOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21–0.87) and increased when the initial provider was a specialist (aOR, 2.96; 95% CI, 2.01–4.38) or a PT (aOR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.01–2.46). The adjusted odds of undergoing radiography within the 1–year period from the index visit was increased when patients sought care from a specialist (aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.16–2.21), but were not different if patients sought care from a PT (aOR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.86–1.64) or DC (aOR, 0.94; 95 CI%, 0.64–1.38).

Discussion

The results of this study were a first look at examining a cohort of patients seeking care for a new episode of neck pain to determine the association of the initial health care provider consulted and subsequent health care utilization. We were specifically interested in comparing the 1–year health care utilization in patients consulting with a nonpharmacological provider, such as a PT or DC, and a pharmacological provider, such as a specialist, to determine how their health care utilization differed from patients consulting with a PCP. We found that initial consultation with a nonpharmacological provider, such as a DC or PT, is associated with a decrease in the downstream utilization of health care services, and importantly a decrease in opioid use 30 days and 1 year after the initial consultation. These findings are consistent with the recent ACP [7, 8] low back and CDC6 opioid prescription guidelines, which favor nonpharmacological interventions often provided by DCs and PTs. [7] There are important practice and policy implications of our findings given current recommendations in favor of front-line nonpharmacological management in patients with neck pain, [19] yet many systems are not structured to provide care in this manner. Stronger alignment of PTs and DCs as front-line providers by health care systems may be needed in light of the widespread addiction, which has been identified as a public health epidemic. [20]

When examining the 1–year health care utilization among the PT and DC providers, there are some important findings to consider. Initial consultation from either a DC or PT decreases the patient's odds of being prescribed an opioid at 30 days or within any time in the 1–year follow-up period. Physical therapists and DCs primarily treat neck pain with exercise therapy and manual therapy, which has been found to have good effectiveness in treating nonspecific neck pain. [21] In contrast, PCPs' first line of treatment often includes medication, imaging, specialist referral, or a combination of those factors, [22] and there is a paucity of evidence-based guidelines for PCPs to inform diagnostic and treatment algorithms. [5] These differences in treatment approaches among PT, DC, and PCP providers may have mitigated the need to prescribe opioids in this sample. At 14 days, there was no difference in opioid use between PCP, PT, or DC, indicating that opioids may not be the first line of pharmacological management for PCPs and it would be consistent with the understanding that PTs and DCs cannot prescribe opioid medication. But there was a decrease in odds of opioid prescription within 30 days of initial consultation, which persists through 1 year, suggesting a lasting protective influence of nonpharmacological providers. Although we were unable to control for prior exposure to opioid use, the persistent decrease in odds of opioid prescription suggests the possibility that prior opioid exposure may not be a substantial factor in increasing the odds of downstream opioid use in patients who initially consult with a PT or DC. But we cannot make the same assumption for consulting with a specialist because prior opioid exposure may be more likely in these patients and may account for the increased odds of opioid use in this sample.

When patients in the sample initially consulted with a DC, the odds of MRI use decreased compared with consulting with a PCP, but not when consulting with a PT. Radiographic studies have been a longstanding mainstay of DC practice. Radiography is routinely ordered as part of a treatment plan and is often performed at the initial visit. It is plausible that the use of radiography may have paradoxically shielded patients from undergoing more advanced imaging such as MRI. When a provider orders imaging, this can alleviate patients' concern about serious pathology, [23] despite a lack of evidence for clinical utility in routine care of patients with neck pain. [24] The increase in the odds of MRI use in patients initiating care with PTs could be explained by a stronger alignment of PTs with traditional medical models of care and reimbursement, in contrast to DCs, who have historically operated outside mainstream health care. [9] In addition, the increase in odds of MRI may indicate that patients initially consulting with a PT may be seeking care from additional providers after the initial consultation.

Initiating care with a specialist was associated with an increase in the odds of receiving spinal injections and undergoing MRI and radiography and had the highest percentage of patients undergoing surgery. Accordingly, comorbid data suggest that these patients had multiple conditions that could potentially affect their choice of provider for a new episode of neck pain. Initially consulting with a specialist for a new episode of neck pain appears to escalate the level of care patients with neck pain receive. These findings may be interpreted in the context of the scope of practice for specialists and the complexity of patients who initially seek care from specialists.

Study Limitations

There are important limitations in this study. We used a primarily claims-based data set to determine the associations with provider type initially consulted for neck pain and downstream health care utilization. Because of the limitations of the nature of variables found in claims data, we were unable to measure or control for all factors that may affect downstream utilization such as prior opioid exposure, severity of symptoms, patient-reported outcomes, or patient factors related to accessing provider. We also examined a cohort of patients insured by one payer in one geographic area, when it is known that there is geographic variability in patients seeking care for neck pain. [25] In addition, we were unable to characterize the severity of patients' neck pain, and therefore we were not able to control for this in statistical analyses. Although we recorded ICD-9 codes for neck pain and comorbidities, we recognize that there are pragmatic limitations and inconsistencies across providers when coding specific neck pain diagnoses, and comorbidities may present similar limitations. Similarly, there were limitations when considering opioid use. We recorded opioid prescriptions for patients in the 1–year period from the index visit, but patients may have been prescribed an opioid for a condition not related to neck pain. In addition, we were unable to control for prior opioid medication exposure before the index visit. Last, there was a large proportion of the sample that was not included in the analysis because of incomplete data (eg, provider at index visit not specified) or low frequency of use for initial consultation in the cohort.

It is worth considering that the differences in health care utilization between patients who initially consult with different providers may be due to selection bias, in which the patients who consult with DCs or PTs appear to be overall “healthier” and patients who consult with a specialist may have more severe or complex symptoms. Although we controlled for comorbidities in the analyses and health care plan type (private, employer-based, and Medicaid), patients initially consulting with a DC or PT had the lowest prevalence of comorbidities with the exceptions of low back pain (DC) and fibromyalgia (PT), which are common comorbid conditions that nonpharmacological providers often treat. Conversely, patients seeking care from specialists had the highest prevalence of all comorbidities except low back pain, indicating that these patients had multiple conditions that could potentially affect their choice of provider for a new episode of neck pain.

Conclusion

These findings support that initiating care with a nonpharmacological provider for a new episode of neck pain may present an opportunity to decrease opioid exposure (DC and PT) and advanced imaging and injections (DC only). Although these findings need confirmation in a better controlled study, our results suggest that adopting such a strategy aligns well with recent CDC and ACP recommendations and has the potential to decrease the management burden of neck pain by PCPs. Future research is needed to examine the association of patient-centered outcomes and health care utilization and to explore whether seeking care from a nonpharmacological provider is also associated with cost savings in addition to decreased health care utilization.

Grant Support:

The work was supported in part by a grant from the Foundation for Physical Therapy's New Investigator Fellowship in Training Initiative. The funding agreement ensured the authors' independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Potential Competing Interests:

The authors report no competing interests.

References:

Fejer R., Kyvik K.O., Hartvigsen J.

The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature.

Eur Spine J. 2006;15(6):834–848Goode A.P., Freburger J., Carey T.

Prevalence, practice patterns, and evidence for chronic neck pain.

Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(11):1594–1601Hurwitz, EL, Li, D, Schneider, MJ et al.

Variations in Patterns of Utilization and Charges for the Care of Neck Pain in North Carolina,

2000 to 2009: A Statewide Claims' Data Analysis

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (May); 39 (4): 240–251

This is one of 3 of the Cost-Effectiveness Triumvirate articles.Fritz JM, Kim J, Dorius J.

Importance of the Type of Provider Seen to Begin Health Care

for a New Episode Low Back Pain: Associations

with Future Utilization and Costs

J Eval Clin Pract. 2016 (Apr); 22 (2): 247–252Teichtahl A.J., McColl G.

An approach to neck pain for the family physician.

Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(11):774–777Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain: United States, 2016

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Recommendations and Reports Vol. 65 No. 1 March 18, 2016Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 493–505Meeker, W., & Haldeman, S. (2002).

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216–227American Physical Therapy Association.

Direct access at the federal level.

http://www.apta.org/FederalIssues/DirectAccess/

Published 2014. Accessed December 6, 2016.Fox J., Haig A.J., Todey B., Challa S.

The effect of required physiatrist consultation on surgery rates for back pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(3):E178–E184Roberts A.W., Dusetzina S.B., Farley J.F.

Revisiting the washout period in the incident user study design: why 6–12 months may not be sufficient.

J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(1):27–35Fritz J.M., Brennan G.P., Hunter S.J.

Physical therapy or advanced imaging as first management strategy following a new consultation

for low back pain in primary care: associations with future health care utilization and charges.

Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1927–1940Haviland M.G., Banta J.E., Przekop P.

Fibromyalgia: prevalence, course, and co-morbidities in hospitalized patients in the United States, 1999-2007.

Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(6, suppl 69):S79–S87Tian T.Y., Zlateva I., Anderson D.R.

Using electronic health records data to identify patients with chronic pain in a primary care setting.

J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e2):e275–e280Rivas-Ruiz R., Moreno-Palacios J., Talavera J.O.

Clinical research XVI. Differences between medians with the Mann-Whitney U test.

Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2013;51(4):414–419.

[in Spanish; abstract available in Spanish from the publisher]Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S, et al.

Course and Prognostic Factors for Neck Pain in Whiplash-associated Disorders (WAD):

Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on< Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S83–92Blozik E., Laptinskaya D., Herrmann-Lingen C.

Depression and anxiety as major determinants of neck pain: a cross-sectional study in general practice.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:13Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD.

Findings From the Bone and Joint Decade 2000 to 2010 Task Force

on Neck Pain and its Associated Disorders

Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2010 (Apr); 52 (4): 424–427Manchikanti L., Helm S., II, Fellows B.

Opioid epidemic in the United States.

Pain Physician. 2012;15(3, suppl):ES9–E38Miller J, Gross A, D'Sylva J, et al.

Manual Therapy and Exercise for Neck Pain: A Systematic Review

Man Ther. 2010 (Aug); 15 (4): 334–354Vos C., Verhagen A., Passchier J., Koes B.

Management of acute neck pain in general practice: a prospective study.

Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(534):23–28Wilson I.B., Dukes K., Greenfield S., Kaplan S., Hillman B.

Patients' role in the use of radiology testing for common office practice complaints.

Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(2):256–263Bussieres A.E., Sales A.E., Ramsay T., Hilles S.M., Grimshaw J.M.

Impact of imaging guidelines on X-ray use among American provider network chiropractors:

interrupted time series analysis.

Spine J. 2014;14(8):1501–1509Freburger J.K., Carey T.S., Holmes G.M.

Management of back and neck pain: who seeks care from physical therapists?

Phys Ther. 2005;85(9):872–886

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 10-07-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |