Low Back Pain of Mechanical Origin:

Randomised Comparison of Chiropractic

and Hospital Outpatient TreatmentThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: British Medical Journal 1990 (Jun 2); 300 (6737): 1431–1437 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank AO

MRC Epidemiology and Medical Care Unit,

Northwick Park Hospital,

Harrow, Middlesex

741 patients, who had neither been treated in the past month nor had contraindications to spinal manipulation, were treated either by doctors of chiropractic or with conventional hospital outpatient treatment for management of low back pain. Using the Oswestry scale, which quantifies pain, patients reported back on their improvement at six weeks, six months, one year and two years. At two years, chiropractic care resulted in a 7 percent benefit over hospital care.

Meade did a follow-up study, published in BMJ 1995 (Aug 5).OBJECTIVE: To compare chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment for managing low back pain of mechanical origin.

DESIGN: Randomised controlled trial. Allocation to chiropractic or hospital management by minimisation to establish groups for analysis of results according to initial referral clinic, length of current episode, history, and severity of back pain. Patients were followed up for up two years.

SETTING: Chiropractic and hospital outpatient clinics in 11 centres.

PATIENTS: 741 Patients aged 18-65 who had no contraindications to manipulation and who had not been treated within the past month.

INTERVENTIONS: Treatment at the discretion of the chiropractors, who used chiropractic manipulation in most patients, or of the hospital staff, who most commonly used Maitland mobilisation or manipulation, or both.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Changes in the score on the Oswestry pain disability questionnaire and in the results of tests of straight leg raising and lumbar flexion.

RESULTS: Chiropractic treatment was more effective than hospital outpatient management, mainly for patients with chronic or severe back pain. A benefit of about 7% points on the Oswestry scale was seen at two years. The benefit of chiropractic treatment became more evident throughout the follow up period. Secondary outcome measures also showed that chiropractic was more beneficial.

CONCLUSIONS: For patients with low back pain in whom manipulation is not contraindicated chiropractic almost certainly confers worthwhile, long term benefit in comparison with hospital outpatient management. The benefit is seen mainly in those with chronic or severe pain. Introducing chiropractic into NHS practice should be considered.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

The high incidence of back pain, its chronic and recurrent nature in many patients, and its contribution as a main cause of absence from work are well known. No general consensus exists about the most effective treatment. Largely anecdotally, patients and therapists often claim great improvements after manipulative treatment by alternative practitioners, including chiropractors. A recent report from the board of science and education of the BMA considered that manipulative treatment ofback pain by lay practitioners may provide "a safe and helpful service," [1] thus strengthening the Cochrane committee's recommendation that randomised trials of treatment for back pain should include an evaluation of heterodox methods. [2]

A comparison of chiropractic with conventional hospital outpatient management of low back pain could take one of two main forms. Firstly, it could be a "pragmatic" trial, which would test what happens in day to day practice and in which details of the type, frequency, and duration of treatment would be at the discretion of the chiropractor or hospital team. [3] The disadvantage of a pragmatic trial is that if a clear difference is found between the treatments it may not be possible to identify the components of the more successful treatment that were responsible. Secondly, it could be a "fastidious" trial, which would compare chiropractic manipulation with a particular form of non-manipulative physiotherapy. [3] Though this type of trial may be more likely to identify specific components of treatment that are effective, there would be a high chance of not including the effective components because of the many techniques used to treat back pain. [4] In addition, its results might have only limited applicability.

We adopted a pragmatic approach for two main reasons: firstly, because of the probable difficulty of securing agreement about standard forms of treatment, particularly in hospital, and consequently the small number of patients who could be recruited into a fastidious trial and, secondly, because the effectiveness oftreatment in day to day practice, whether chiropractic or in hospital, is of most immediate interest to patients as well as doctors and therapists.

Patients and methods

CENTRES AND CLINICS

The study was based on the methods of a feasibility study. [5] Each centre consisted of a chiropractic clinic and a hospital clinic. After the feasibility studv had been completed 11 centres with hospital and chiropractic clinics within a reasonable distance of one another agreed to take part in this trial.

PATIENTS

The main criterion for eligibility was that patients should have no contraindication to manipulation as almost all the patients treated by chiropractic would receive manipulation and it was important to avoid damage by manipulation. Thus patients were excluded if there was evidence that a nerve root was affected, though restricted straight leg raising on its own was not a reason for exclusion; major structural abnormalities were visible on radiography; or osteopenia or an infectious cause was suspected and for various other reasons, including social conditions and pending litigation. Only patients aged 18 to 65 who had not been treated within the past month and who had not attended the same referral clinic within the past two years were recruited.

Table 1

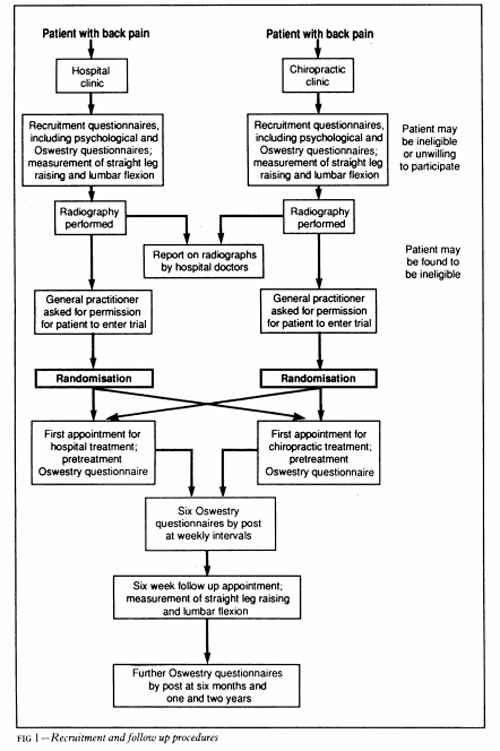

Figure 1 Two of the 11 centres kept a record of all patients presenting with back pain. Table I summarises the reasons for ineligibility or exclusion in these two centres, confirming the general finding of the feasibility study in one of the other centres that contraindications were commoner among patients presenting initially to hospital while considerations of convenience-for example, to avoid waiting and delay in starting treatment- were commoner among patients initially presenting to the chiropractors. Among 135 eligible patients referred to hospital 108 (80%) entered the trial, compared with 67 of 239 (28%) referred to chiropractors. In all, 175 (47%) of those eligible in these two centres entered. Figure 1 summarises the recruitment, investigation, treatment, and follow up procedures in eligible patients.

All patients underwent radiography of the lumbar spine, the x ray films (whether taken by the chiropractor or in hospital) being reported on by a hospital radiologist. Permission was then sought from general practitioners for each patient's participation in order to comply with the General Medical Council's advisory guidelines about collaboration with heterodox practitioners. Two general practitioners in one centre said that they did not want any of their patients included. Permission was also withheld for five patients under other general practitioners. The General Medical Council also advised that the medically qualified members of the hospital teams should satisfy themselves about the competence of the chiropractors. This was done through discussions during the early stages of the trial.

The purpose of the trial was explained to eligible patients by the nurse coordinator in each centre, who pointed out that participation would mean an equal chance of being treated by chiropractic or conventional hospital methods, the decision being made at random. Patients were also given a written explanation and told that if they were allocated for treatment at the clinic they had not originally attended they would be free at any stage to return to the original clinic. All patients signed a consent form, and the study was approved by the ethical committees of the 11 centres.

The fees of patients receiving chiropractic treatment were paid by grants from funding agencies regardless of whether these patients had originally attended chiropractic or hospital clinics. The number of patients recruited in each centre ranged from 14 to 198.

General practitioners in three centres had direct access to physiotherapy departments for all or part of the trial, accounting for the higher proportion of patients with short episodes of pain compared with that in the feasibility study. [5]

OUTCOME

The patients' progress was measured with the Oswestry back pain questionnaire, [6] which gives scores for 10 sections-for example, intensity of pain, difficulty with lifting, walking, and travelling. The result is expressed on a scale ranging from 0% (no pain or difficulties) to 100% (highest score for pain or difficulty on all items). Each patient completed the questionnaire at recruitment and shortly before starting treatment. Further questionnaires were then sent by post with prepaid reply envelopes at weekly intervals for six weeks, at six months, and at one and two years after entry. Subsidiary measures of outcome included assessing straight leg raising with a goniometer [7] and lumbar flexion [8]; both were measured at entry and at six weeks by the coordinating nurse, the readings made at entry being unavailable to her at the six week follow up appointment. The results reported here include the responses to follow up questionnaires and other measures completed by the end of September 1989, when all patients had been followed up for six months, fewer patients having completed one and two year follow up questionnaires.

At entry patients also completed psychological questionnaires dealing with depressive symptoms, somatic awareness, and inappropriate symptoms. [9]

TREATMENT

Each patient's treatment was at the discretion of the chiropractor or hospital team. Based on the pattern of chiropractic treatments in the feasibility study and in discussion with a representative of the British Chiropractic Association the chiropractors were allowed to give a maximum of 10 treatments, which were intended to be concentrated within the first three months but could be spread over a year if considered necessary.

STATISTICS

Table 2 We recruited as many patients as the available funding allowed. We estimated from the feasibility study that about 2000 patients would be needed to detect a difference between the two approaches of 2% points on the Oswestry scale (at the 5% level, with 90% power) - for example, a decrease in Oswestry score from 30% to 25% in one group compared with a decrease from 30% to 23% in the other - and that differences of 2-5%, 3 0%, 4 0% and 5 0% points would require about 1200, 850, 500, and 300 patients respectively. Table II gives examples ofthe implications of a range of differences in mean Oswestry scores.

Patients were randomly allocated to treatment, and the method of minimisation [10] was used within each centre to establish groups for analysis of results according to initial referral clinic, length of current episode (more or less than a month), presence or absence of a history of back pain, and an Oswestry score at entry of >40% or ≤40%. The feasibility study had shown that the length of the current episode, in particular, clearly distinguished two groups of patients, those with a short current episode improving much more rapidly (regardless of treatment) than those with longer episodes. [5]

Table 3

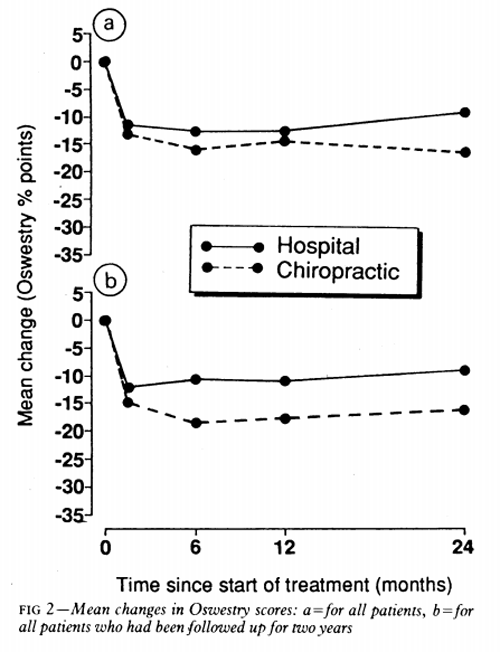

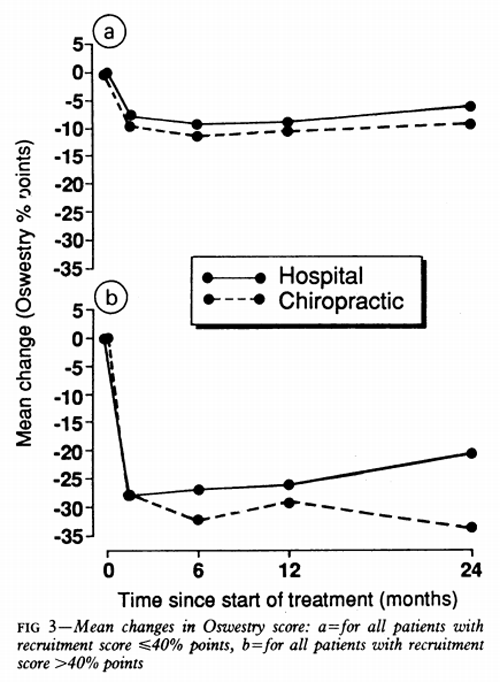

Figure 2

Figure 3 The interval between recruitment and the start of treatment varied slightly among the four referral and treatment clinic groups. To allow for any changes before the start of treatment the results were based on changes in Oswestry scores, and this also allowed for the small differences in pretreatment scores between the hospital and chiropractic groups (see table III).

The negative sign for changes in Oswestry scores in Figures 2 and 3 means a fall - that is an improvement in these scores (between pretreatment and follow up) - reflecting the well known tendency for back pain to improve spontaneously as well as any treatment effects. (Similar figures for results according to referral clinic, length of current episode, and past history are available on request.)

The results were analysed by intention to ti (subject to availability of data on follow up and at en for individual patients). Differences between the ml changes in the two groups were tested by unpaire tests. χ2 Tests were used to detect any signific differences between the two treatment groups - for example, in the proportion of patients off work. Missing data account for slightly differing number the text and tables.

Results

Patients were recruited during March 1986 to Ma 1989. In all, 781 patients were recruited from the participating centres. Of these, 24 (13 from hospitals and 11 from chiropractic clinics) were later found to be ineligible and 16 (eight, eight) withdrew from the study almost immediately so that 741 started treatment (384 receiving chiropractic and 357 hospital treatment.) Table III summarises the characteristics of the patients in the two treatment groups.

Follow up Oswestry questionnaires were returned by 90% patients at six weeks, by 84% at six monnths (86% treated by chiropractors, 81% in hospital), by 79% at a year (83% chiropractors, 74% hospital) and by 72% at two years (76% chiropractors, 69% hospital). Because non-response was more common among patients treated in hospital than by chiropractors and randomisation had by chance resulted in a few more patients being allocated to chiropractors (see above) there were usually more patients treated by chiropractors than in hospitals in the analyses. There were no obvious systematic differences in the characteristics of non-responders treated by chiropractors or in hospital.

Table 4 Table IV summarises the treatments received in the chiropractic and hospital clinics. Not all hospitals had access to hydrotherapy, but otherwise there were no appreciable differences in treatment patterns among hospitals. Virtually all the patients treated by chiropractors received chiropractic manipulation such as high velocity, low amplitude manipulation at some stage. Patients treated by chiropractors received about 44% more treatments than those treated in hospitals. At six weeks 79% of hospital patients had completed treatment compared with 29% of patients treated by chiropractic. Almost all patients had completed treatment by 12 weeks in the hospital group and by 30 weeks in the chiropractic group (97%). The chiropractors generally treated all patients over a similar period whereas the hospital therapists treated patients with long episodes of back pain who were never free of symptoms for longer periods than those with short episodes.

Of the 741 patients who started treatment, 29 changed their treatment centre (22 within the first six weeks). Sixty patients did not complete their course of treatment and 77 did not attend for six week follow up with the nurse coordinator. Altogether 608 completed the trial to six weeks without missing any treatments or the six week questionnaire, changing treatment centre, or missing follow up appointments.

Table 5 Table V gives the differences in the changes in Oswestry scores between the two treatment groups. Figure 2a, which is based on all data for all patients, shows that the change for those treated by chiropractic was consistently greater than that for those treated in hospital. At two years the patients treated by chiropractic had improved by 7% more than those treated in 24 hospital (p = 0.01). When the analysis was confined to patients all of whom had been followed up for two years and who had complete data at six weeks, six months, one year, and two years the general pattern was similar (Figure 2b) but the differences at six months and a year were greater. Among patients who originally attended hospital there was no difference between chiropractic and hospital treatment until two years after entry, when the patients treated by the chiropractors had imnproved more than those treated in hospital (Table V).

For patients who originally attended a chiropractor the chiropractic treatment was more effective throughout the follow up period. When the results were confined to patients with complete follow up data for two years, however, the patients in both referral groups who were treated by chiropractic tended to show greater improvement throughout the follow up.

The results were also analysed according to length of the current episode of pain. In both groups those treated by chiropractors improved more than those treated in hospital, the benefit possibly being seen somewhat earlier in those with a long current episode (Table V). There was no difference between the two treatments in those with no history of back pain, but chiropractic treatment was more effective than hospital treatment in those with a history. Figure 3 shows that those with Oswestry scores >40% at entry responded better to chiropractic treatment (by 13% at two years) than those with scores ≤40%.

Between follow up at one and two years 17% (18/107) of those initially treated by chiropractors had further chiropractic treatment and 24% (22/92) of those initially treated in hospital had further hospital treatment.

Thus the tendency for the changes in the Oswestry score to remain in favour of chiropractic during the second year was probably not due to a disproportionate reinforcement from further chiropractic treatment during this period.

In only one centre was hospital treatment possibly more effective than chiropractic, by 3% and 1% on the Oswestry scale at six months and two years respectively. This centre recruited many patients, mostly through open access arrangements, and omitting its results increased the apparent effectiveness of chiropractic treatment in the 10 other centres. Two centres showed little if any difference between chiropractic and hospital treatment, and in eight chiropractic was more effective. No clear relation was found between the number of treatments and extent of improvement for either chiropractic or hospital treatment.

Table 6 Table VI shows that the change in straight leg raising and lumbar flexion was greater in those treated by chiropractic than those treated in hospital and that for nearly all other subsidiary measures patients treated by chiropractors did better than those treated in hospital. The smaller proportions of patients treated in hospital than by chiropractic who were satisfied with their treatment or relieved by it may well account for the somewhat greater loss to follow up in the hospital group. Because treatment for those allocated to chiropractic lasted longer than that for those allocated to hospital effects on time off work during the first year were difficult to assess. Between one and two years the frequency and duration of absence from work were less in those treated by chiropractic. Of those with jobs, 21% (18/84) of patients given chiropractic had time off work because of back pain compared with 35% (26/74) of hospital patients (p = 0.055).

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS

The potential economic, resource, and policy implications of our results are extensive. The average cost of chiropractic investigation and treatment at 1988-9 prices was £165 per patient compared with £111 for hospital treatment. Some 300,000 patients are referred to hospital for back pain each year, [11] of whom about 72,000 would be expected to have no contraindications to manipulation. [12] If all these patients were referred for chiropractic instead of hospital treatment the annual cost would be about £4m. Our results suggest that there might be a reduction of some 290,000 days in sickness absence during two years, saving about £13m in output and £2.9m in social security payments. As it was not clear, however, that the improvement in those treated by chiropractic was related to the number of treatments the cost of essential chiropractic treatment might be substantially less than £4m. The possibility that patients treated in hospital would need more treatment during the second year than those treated by chiropractic (see above and Table VI) also has to be borne in mind. There is, therefore, economic support for use of chiropractic in low back pain, though the obvious clinical improvement in pain and disability attributable to chiropractic treatment is in itself an adequate reason for considering the use of chiropractic.

Discussion

Though many randomised controlled trials of treatments for back pain have been carried out, there have so far been no clear indications in favour of any particular method. The place of manipulation in back pain has been reviewed by Jayson, [13] who concluded that any minor benefits seemed to be confined to those with acute pain of recent onset, that there was no evidence that manipulation helped those with severe or chronic back problems, and that it did not reduce long term complications or prevent recurrences. For chiropractic our findings suggest otherwise. The difficulties of clinical trials in low back pain have been discussed. [14] Our trial had the combined advantages of considerably larger numbers and a longer follow up period than other trials comparing orthodox treatments or, less often, orthodox and alternative treatments.

We studied only patients who had no contraindications to manipulation. Although this group represents a substantial proportion of all patients with back pain, the findings cannot be automatically applied to all patients with back pain. With this proviso the results leave little doubt that chiropractic is more effective than conventional hospital outpatient treatment. The confidence intervals for the differences in Oswestry scores were wide, but the degree of improvement recorded for many of the secondary outcome measures (Table VI) suggests that chiropractic has appreciable benefit. The effects of chiropractic seem to be long term, as there was no consistent evidence of a return to pretreatment Oswestry scores during the two years of follow up, whereas those treated in hospital may have begun to deteriorate after six months or a year.

Chiropractic was particularly effective in those with fairly intractable pain - that is, those with a history and severe pain. Although we have discussed the results in terms of differences at the various follow up intervals, the full effects of treatment are better thought of as an integrated benefit throughout the two year follow up period, represented by the area between the curves for the two treatments. The greater proportions of patients treated by chiropractic who were satisfied and relieved at six weeks, when 90% of patients had provided follow up data, strengthens the likelihood that the differences in Oswestry scores and other variables later on, when fewer patients have provided data, were true differences.

The results from the secondary outcome measures (Table VI) suggest that the advantage of chiropractic starts soon after treatment begins. The reason for the much larger advantage later on is not obvious. Part of the explanation could be that hospital treatment is effective in the short term but not the longer term, perhaps because it is not given for as long as chiropractic. The undoubted difficulties under which some of the participating physiotherapy departments were working during the trial almost certainly meant that they were unable to give all the specific treatment they would have wished to all patients.

A central question is the extent to which the results could be due to biases and placebo effects. Patients were deliberately sent follow up Oswestry questionnaires at home to minimise any chance that their answers might be affected by actual or perceived influence by their therapist. Ideally, straight leg raising and lumbar flexion should have been measured by an assessor who was blind to the treatment allocation. The nurse coordinators, however, did not have the initial results available at the time of the follow up measurements at six weeks. In addition nearly all the other subsidiary measures suggested greater improvement among those treated by chiropractic.

The consequences of biased outcome measures or of a placebo effect associated with chiropractic would almost certainly have been more evident when treatment was still in progress or just afterwards. In fact, the main difference between hospital and chiropractic treatment was seen from six months or a year onwards, well after treatment and contact with therapists had ended.

The fact that chiropractic treatment tended to be more effective in those initially presenting to the chiropractors than in those presenting to hospital raises the possibility that the self assessment by the patients who presented to chiropractors may have been influenced by their expectation that chiropractic would be effective. The results in all patients who had been followed up for two years, however, indicate a similar effect of chiropractic in both referral groups (Table V). There were several differences between the two referral groups that may have influenced response to treatment (these will be reported in detail elsewhere). For example, a significantly higher proportion of patients initially attending the chiropractors had had previous episodes of back pain. Those initially attending chiropractors had also waited much less time for appointments for the current episode and scored significantly less on questionnaires for depressive and inappropriate symptoms and for somatic awareness than the patients initially attending hospital.

In addition, the analyses among the (non-clinic) subgroups prespecified in the minimisation procedure were balanced for referral clinic, there being similar proportions initially presenting to chiropractors and to hospital in each of the randomised treatment groups. Yet the tendency for chiropractic to be more effective was not universal - for example, the absence of clear benefit in those with no previous history of back pain. Finally, the self exclusion of many patients who initially presented to the chiropractors probably resulted in only a few of these patients who might automatically have assessed themselves as better after chiropractic or worse after hospital treatment being included. In summary, it is unlikely that the benefits of chiropractic are the result of biased outcome assessments or of a placebo effect.

Centres where chiropractic was more effective at six weeks and six months and those where there was less difference between the two treatments at that stage contributed to the results to about the same extent at a year and two years. The sustained effect of chiropractic was therefore probably not due to a disproportionate contribution from individual centres where there was an obvious early benefit from chiropractic.

In the absence of any clear relation between the number of treatment sessions and outcome, specific components ofchiropractic responsible for its effectiveness have to be considered. An obvious possibility is the use of high velocity, low amplitude manipulation in virtually all the patients treated by chiropractic. Another is that chiropractic was given for a longer period than hospital treatment. Whatever the explanation for the difference between the two approaches, however, this pragmatic comparison of two types of treatment used in day to day practice shows that patients treated by chiropractors were not only no worse off than those treated in hospital but almost certainly fared considerably better and that they maintained their improvement for at least two years.

If our results are more widely applicable the practical implications are far reaching. Consideration should be given to recognising appropriately trained and experienced chiropractors and to providing chiropractic within the NHS, either in hospitals or by purchasing chiropractic treatment in existing clinics. Further trials to identify the specific component(s) responsible for the effectiveness of chiropractic should be undertaken. Whether the results of this trial can also be applied to other heterodox regimens of manipulation is an open question.

We thank the nurse coordinators, medical staff, physiotherapists, and chiropractors in the 11 centres for their work, and Mr Alan Breen of the British Chiropractic Association for his help. The centres were in Harrow, Taunton, Plymouth, Bournemouth and Poole, Oswestry, Chertsey, Liverpool, Chelmsford, Birmingham, Exeter, and Leeds. Without the assistance of many staff members in each the trial could not have been completed. The study was supported by the Medical Research Council, the National Back Pain Association, the European Chiropractors Union, and the King Edward's Hospital Fund for London.

ADDENDUM- In view of the long term benefit apparently due to chiropractic we initiated a three year follow up, sending multiple reminders to those initially not responding. By mid April 1990 - beyond the closing date for the earlier results - data were available for 113 patients, representing a 79% response. At three years the mean fall in Oswestry score for those treated by chiropractic was 9.6% points more than for those treated in hospital (p = 0.01). The fall was greater (13.8% p = 0.003) among those presenting with current episodes of more than a month's duration than for those presenting with episodes of less than a month (5.3%, NS). Among those with a previous history of back pain, the improvement in Oswestry score at three years was 9.7% points greater in patients treated by chiropractic than those treated in hospital (p=002). A similar difference between the two forms of treatment (9.4%) was found among those with no previous history of back pain, but numbers in this group were smaller and the difference was not significant.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Return to COST EFFECTIVENESS JOINT STATEMENT

Since 8-11-1998

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |