Integrated Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Care

at a Comprehensive Combat and

Complex Casualty Care ProgramThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 781–791 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Capt Kathy F. Goldberg, PT, MA, Bart Green, DC, MSEd, Jacqueline Moore, MPT,

Marilynn Wyatt, MA, PT, Lynn Boulanger, MS, OTR/L, Brian Belnap, DO,

Peter Harsch, MA, David S. Donaldson, MS

Naval Medical Center,

San Diego, CA, USA.OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study is to describe the musculoskeletal rehabilitation model used to care for combat and severely wounded or ill US military service members at an integrated Comprehensive Combat and Complex Casualty Care center located at Naval Medical Center San Diego.

METHODS: Through a collaborative and iterative process, providers from the various services included at the Comprehensive Combat and Complex Casualty Care program developed a description of the integration of services provided at this location.

RESULTS: After construction of the facility in 2007, the program has provided services for approximately 2 years. Eighteen different health care providers from 10 different specialties provide integrated musculoskeletal services, which include primary care, physical therapy, occupational therapy, vestibular therapy, gait analysis, prosthetics, recreational therapy, and chiropractic care. At the time of this writing (early 2009), the program had provided musculoskeletal rehabilitation care to approximately 500 patients, 58 with amputations, from the operational theater, Veterans Affairs, other military treatment facilities, and local trauma centers.

CONCLUSION: The complex nature of combat wounded and polytrauma patients requires an integrated and interdisciplinary team that is innovative, adaptable, and focused on the needs of the patient. This article presents a description of the model and the experiences of our musculoskeletal rehabilitation team; it is our hope that this article will assist other centers and add to the small but emerging literature on this topic.

Key Indexing Terms: Military Medicine, Hospitals, Veterans, Military Personnel, Delivery of Health Care, Integrated, Physical Medicine, Chiropractic, Physical Therapy (Specialty), Occupational Therapy

The Full-Text Article:

Introduction

Advances in body armor and early acute trauma intervention have led to decreases in combat mortality. [1] However, although more catastrophic war time injuries can be treated, it has led to an increase in survivor morbidity and challenges to medical resources. [2, 3] Improvised explosive devices and rocket-propelled grenades cause severe blast injuries that are made worse because these devices contain contaminating substances, such as dirt, glass, and other debris. These injuries result in polytrauma, which affect multiple body systems [4, 5] and require lengthy and comprehensive rehabilitation. [4] Polytrauma has been defined as “… injury to the brain in addition to other body parts or systems resulting in physical, cognitive, psychological, or psychosocial impairments and functional disability.” [6]

United States military service members (SMs) with severe injuries or illnesses are medically evacuated from the combat theater or other locations and admitted to inpatient care at a major medical center. If a SM sustains severe injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) or Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan, he or she is typically evacuated to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany for initial trauma stabilization and subsequently returned to the United States. [2] The high number of casualties at the beginning of OIF received long-term rehabilitation at one of two centers — the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC, or the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Tex. [1] Patient data from returning SMs revealed that approximately 25% of all injured military members were stationed at West Coast military installations (commands) or were West Coast residents. Many of the injured were Marines from Camp Pendleton and Twenty-Nine Palms in California or soldiers from Ft Irwin (California) and other locations in the West. Thus, when an SM from the Western United States needed extensive rehabilitation, he or she would have to reside at either Walter Reed or Brooke Army Medical Center, far removed from family and support structure. It was clear that a third center was needed to treat the long-term injuries of returning West Coast SMs. As an already established tertiary care center with specialty services in place, Naval Medical Center San Diego (NMCSD) was the logical choice for the site of this West Coast center.

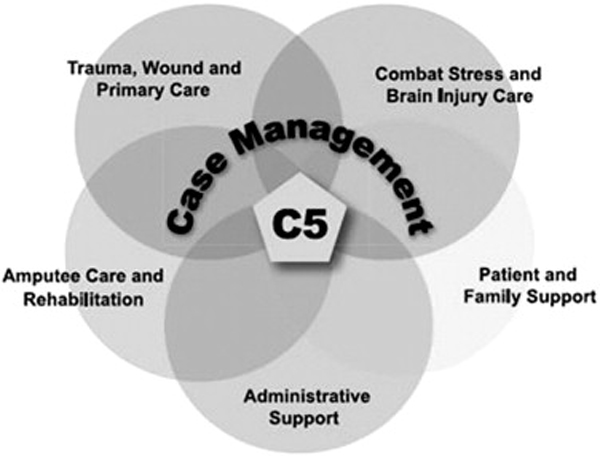

A $4.4 million renovation project was planned in 2006 to support NMCSD's Comprehensive Combat and Complex Casualty Care (C5) rehabilitation program. This area, which opened in October 2007, provides a high level of interdisciplinary treatment to patients with polytraumatic injuries, including amputations, traumatic brain injuries, posttraumatic stress disorder, and multiple orthopedic injuries. C5 offers state-of-the-art rehabilitation to combat and complex patients while keeping them close to home and their military unit. Caring for polytrauma patients requires a well-trained interdisciplinary team of health care professionals, peer support, community reintegration, and family support [7] to address wounds to the body, mind, and soul, as represented in Figure 1. The purpose of this article is to describe the development, breadth, and scope of the integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation services provided at C5 in an effort to contribute to the emerging literature pertaining to the care of complex injuries in the modern military environment.

Description

C5 Facility

C5 rehabilitation services are located in the NMCSD complex. NMCSD is a comprehensive military health care system in the Western United States, with a full array of inpatient and outpatient services. The C5 facilities are situated on the ground floor, which grants easy access for patients who experience difficulty with ambulation, and are located within the physical therapy and occupational therapy department. The total area of the C5 facilities exceeds 30,000 ft2 and includes a modern physical therapy gym, fully functional training apartment, gait analysis laboratory with real-time computerized 3-dimensional motion analysis, high-tech prosthetic laboratory, therapeutic pool, primary care suite, and numerous treatment areas. The building complex is designed in a large rectangular loop, with an outdoor 3.500 ft2 courtyard in the center that contains a 30-ft climbing wall, ramps, stairs, and beams that permit patients to work on advanced ambulation and balance activities. Sand, gravel, rock, and brick terrains simulate surfaces encountered in everyday communities (Fig 2).

The C5 facility was developed to be aesthetically pleasing, with warm colors, interesting artwork (created by local disabled artists, including C5 patients), nonskid floors (in consideration of those with assistive devices and prostheses), and a spacious entrance lobby and reception area. The loop design uses “way finding” elements to offer cues to patients proceeding to the various clinics; different-colored lighting outside clinic entrances, along with changes in floor colors and patterns, helps improve directions and makes it easier for patients to navigate the Center. The use of natural lighting and soothing colors adds to the recovery process.

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation/Primary Care

as Hub for Coordination of Services

Physical medicine and rehabilitation/primary care (PM&R/PC) is the hub of the C5 musculoskeletal rehabilitation model. The clinic space is approximately 1,000 ft2 and consists of a reception area, 3 offices, 3 examination rooms, and 1 treatment room. The clinic remains open Monday through Friday from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM. The providers include 1 physician assistant, 2 nurse practitioners, and 1 PM&R physician (all full-time). Primary care capabilities include comprehensive physical examinations, wound care, therapeutic injections, gynecologic examinations, and administration of intravenous medications. All C5 patients, once they are discharged from an inpatient setting or arrive from theater via commercial air, are evaluated within 1 business day by a primary care provider. Comprehensive evaluations are conducted, including careful screening for traumatic brain injury and mental health issues that are not always readily apparent in those individuals with combat exposure. A pharmacist attends this clinic 1 day per week to review individual medications with C5 patients who require the use of more than 1 medication. A medical assistant is available to provide and reinforce any needed patient education on a variety of issues, such as medications, pain management, and wound care.

The physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) services are available for inpatient and outpatient consultation regarding musculoskeletal injuries, amputation, spinal cord injuries, traumatic brain injuries, and polytraumatic injuries. One of the primary responsibilities of PM&R is to provide clinical oversight and conduct weekly multidisciplinary amputee clinics, team meetings, and care conferences. PM&R also actively participates with the inpatient C5 trauma service and traumatic brain injury multidisciplinary team.

Although amputation of irreparable limbs after combat injury is less common today than in previous conflicts, amputation is still necessary in approximately 2% to 3% of OIF or OEF wounded US SMs. [1] Primary care works to aid patients with the various types of pain they may experience, including postsurgical pain, residual limb pain, phantom limb pain, and prosthetic pain. [8] Residual limb pain is pain experienced in the remaining stump after amputation and is often the result of the formation of a neuroma or heterotopic ossification. [9] Phantom limb pain occurs when patients perceive pain from the removed limb, which may also be accompanied by sensations such as pressure, temperature, and tingling. [9] Secondary sources and locations of pain are also a common problem for amputees, with back pain being reported to be prevalent in 52% to 71% of people in the United States after amputation. [10] Clark et al [2] reported that head and low back pain accounts for 75% of secondary pain in a sample of 50 OIF/OEF veterans, followed by facial, hand, leg, neck, and abdomen pain. Primary care initiates pain management and refers patients to other members of the C5 team to help alleviate pain. Typically, PC will order consults to various specialty clinics, based upon the needs of each patient. Thus, each C5 patient may have a team of specialty providers that he or she may visit multiple times per week.

The C5 team recognizes the tremendous challenge of maintaining good communication with patients and the many medical and nonmedical team members involved with the care of each C5 patient. To address this issue, the C5 team uses an integrated and interdisciplinary team approach with case management as the central key component. Case managers are immediately assigned to each patient upon his/her arrival and are responsible for conducting a medical and nonmedical needs assessment to identify and address individual requirements of the patient and family members. Case managers work closely with the medical team, military liaisons, patient family members, and other available resources to ensure that all needs are met. Thus, case managers help greatly to coordinate specialty consults and the numerous appointments of C5 patients.

Specialty Staffing and Communications

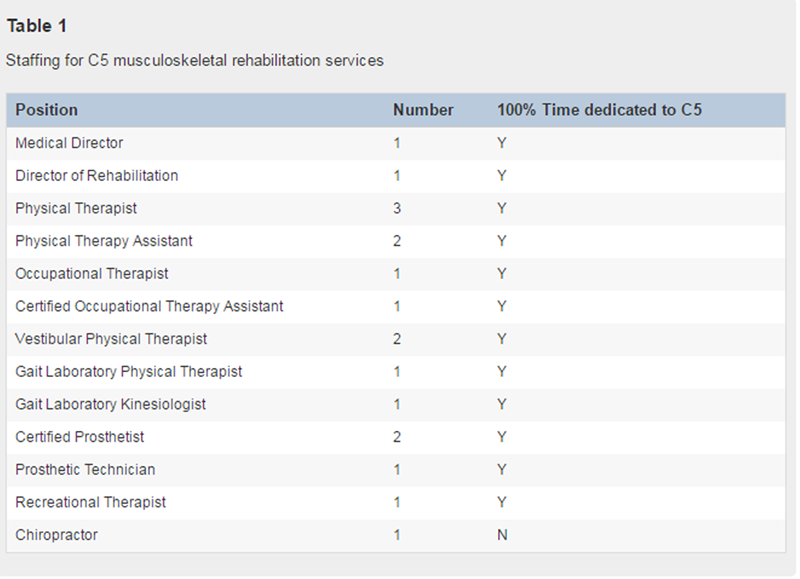

By the very nature of their injuries, C5 patients are complex and often require the expertise of multiple providers and services; hence, many highly trained providers are on board to deliver care. Specifically, the rehabilitation team is composed of 18 members representing 10 different areas of specialization (Table 1). Two of the team members serve as military officers and the rest are civilian employees or contractors. Although most specialty consults originate from PC, specialty providers may also make a consult to a fellow specialty provider if necessary.

Communication between the PC provider and specialty providers and among the specialty providers is important. Several mechanisms exist to facilitate dialog. Formally, there is a weekly meeting where most of the members of the musculoskeletal rehabilitation team meet with other providers caring for C5 patients to discuss cases and coordinate care. Informally, in the musculoskeletal rehabilitation physical space, it is easy for specialty providers to meet either in an office or in clinic, as the physical layout is very open and conducive to interactions. For example, the gait analysis laboratory is located around the corner from physical therapy; and a provider from either division can easily walk around the corner to discuss a case with a colleague, a situation that all divisions have in common because of the loop design of the facility. Further communication through telephone and e-mail is frequently used among specialty providers and to/from primary care.

Physical Therapy

The C5 physical therapy (PT) division provides neuromusculoskeletal rehabilitation services to patients referred with polytrauma, to include amputations, multiple fractures, nerve injuries, soft tissue injuries, and/or traumatic brain injury (Figure 3). Most patients are injured in combat from improvised explosive devices or gunshots; but the C5 PT division also treats patients injured in motor vehicle accidents, motorcycle accidents, and training accidents. C5 PT has 5 full-time staff members, 3 physical therapists, and 2 physical therapy assistants. Of these, 3 are certified athletic trainers, 2 are certified strength and conditioning specialists, and 1 is a PT orthopedic clinical specialist. One of the physical therapy assistants is currently working on her physical therapy degree.

Patients referred to C5 PT are initially evaluated by a physical therapist. Based upon the assessment of their impairments, treatment appointments are scheduled for 2, 3, or 5 days per week. Patients are treated by either a physical therapist or physical therapy assistant during each session. An earnest attempt is made to address all areas during each patient's treatment session, including strengthening, conditioning, flexibility, balance, gait training, and functional activities. Emphasis is placed on core strengthening, when possible, as an important adjunct to balance and gait training. Patients are also able to participate in various group activities, including aquatic therapy and functional training classes. Class participation is determined by the patient's primary physical therapist.

In addition to traditional physical therapy equipment, such as mat treatment tables, upper body ergometers, treadmills, stationary bicycles, and various therapeutic modalities, the C5 PT clinic uses special equipment for certain aspects of rehabilitation. Some unique items are the G-Trainer Antigravity Treadmill (AlterG Inc, Menlo Park, Calif), the Proprio 5000 (Perry Dynamics, Inc, Decatur, Ill), Solo-Step (Solo-Step Inc, Sioux Falls, SD), and the Functional Squat System (Monitored Rehab Systems, Ft Worth, Tex). The G-Trainer is an unweighting system that uses positive air pressure to set a patient's body weight as low as 20% while running or walking on a treadmill. The therapist or patient can adjust body weight, speed, incline, and/or belt direction to provide the best possible parameters for the patient's treatment goals and to reduce ground reaction forces during rehabilitation. [11] The Proprio 5000 is a dynamic balance system that provides reactive testing and training [12] and is particularly useful for patients with vestibular disorders and/or amputations. The Solo-Step is a ceiling-mounted aluminum track and trolley that attach to a harness that the patient wears while training; the device allows for hands-free gait training that enables the therapist to observe the patient from all sides. The Functional Squat System is a closed-chain system for testing and rehabilitation. The patient can perform traditional squats of certain repetitions and sets or can play games on the equipment as part of his or her strengthening session. The C5 PT division also uses real-time ultrasound to assist patients with achieving transverse abdominis muscle contraction, [13] which can assist with balance and endurance during their rehabilitation sessions.

Gait Analysis Laboratory

The gait analysis laboratory, another component of the C5 rehabilitation program, is a 720-ft2 motion capture space (Figure 4), with an adjacent examination room, office, and workspace located within the rehabilitation department. The laboratory allows patients easy access to the facility. The technology includes a 10-camera Motion Analysis Corporation (Santa Rosa, Calif) motion capture system, 4 AMTI (Watertown, Mass) force platforms embedded in the floor, 16-channel Konigsburg (Pasadena, Calif) electromyography system, and 2 Canon XHA1 (Lake Success, NY) video cameras placed orthogonally to the walkway. These systems provide the capability to collect 3-dimensional kinematic and kinetic data, both surface and fine-wire kinesiological electromyographic data, and video images, all synchronized in real time. Data processing and analysis are performed via proprietary Motion Analysis Corporation software or high-powered and multifunctional Visual3D (C-Motion, Inc, Germantown, Md) software.

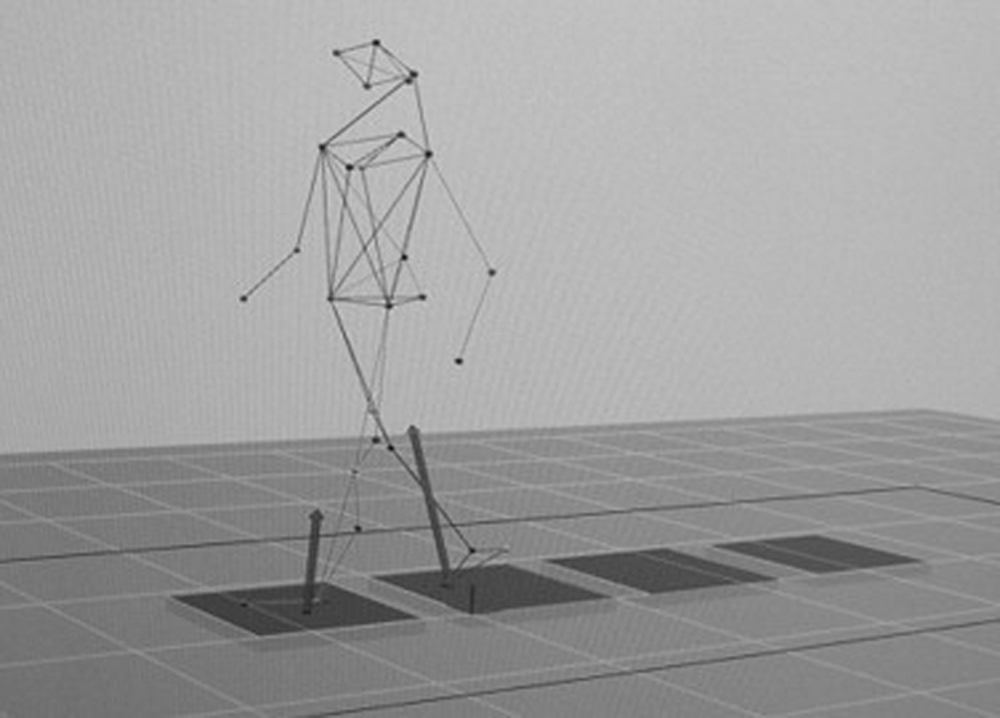

Currently, all ambulatory patients with lower extremity amputations are being followed with sequential studies in the gait analysis laboratory. Patients are studied in the gait laboratory once they are capable of walking the length of the laboratory (about 30 ft) without the use of assistive devices. The gait study begins by placing 30 reflective markers on anatomical landmarks of the upper and lower extremities, torso, and head of the patient (Figure 5). Once markers are placed, the patient is asked to walk across the walkway while multiple gait cycles of data are collected. After the patient leaves, data collected from these walks are processed and plotted into a graphical report to allow for analysis (Figure 6). The data are interpreted, taking into consideration the patient's history and physical examination findings; and the primary gait deviations are identified. Findings are then reviewed by the interdisciplinary team, and treatment objectives are discussed to further the care of the patient. A final report is put into the electronic medical record for reference by the whole team. Gait studies performed at set times during the rehabilitation process have provided documentation of the patient's progress, as well as recommendations for treatment or prosthetic modifications, and have contributed to the excellent care these patients receive by this interdisciplinary program. The laboratory is staffed by personnel with expertise in gait, biomechanics, and interpretation of the data for clinical benefit.

Figure 6. A graphical gait analysis report showing a

3-dimensional image of a subject on the force plates.

Occupational Therapy

The occupational therapy (OT) division of C5 treats SMs with complex or combat-related injuries from OIF and OEF, in addition to non–combat-related injuries that are complex and considered part of the C5 program. Occupational therapy has a full training apartment attached to the hand clinic that gives patients the opportunity to practice tasks in an environment similar to what they will encounter upon discharge. The apartment includes a fully operational kitchen, complete with microwave oven, range top stove/oven combination, refrigerator, and dishwasher. Also in the training apartment are a bedroom and handicapped bathroom with a shower-tub to teach patients and their caregivers about transferring in and out of bathing facilities. A living room is also offered; and a computer workstation, with 1-handed keyboards, print enlargers, and voice-activated technology, is available for ergonomic assessment and adaptive technology training. Presently, the facility has 1 full-time C5-designated occupational therapist, who has additional training and certification as a hand therapist. C5 OT is complemented by a full-time certified occupational therapy assistant.

C5 OT provides inpatient and outpatient care. Inpatient goals are tailored toward maximizing independence with activities of daily living (ADLs) (Figure 7) and endurance until the patient is suited for transition to continued care in the outpatient setting. Comprehensive services are provided to all patients with amputations. Patients with amputations are taught techniques to help manage phantom limb pain through mirror therapy and other nonpharmacologic modalities. The division actively assists in scar mobilization, myofascial release, desensitization, and promoting postural stability/balance, conditioning, and functional tasks that lead to independence in ADLs. Patients with upper extremity amputations are additionally trained using the MyoBoy (Otto Bock HealthCare, Duderstadt, Germany), a computerized program that evaluates, trains, and assists in prosthetic component selection and helps anticipate potential problems. Patients complete functional activity checklists provided by prosthetic companies that cover aspects of ADLs both with and without use of their prosthesis.

In addition to caring for patients with amputations, C5 OT treats a variety of upper extremity injuries, to include burns, gunshot wounds, shrapnel/blast injuries, crush injuries, fractures, peripheral nerve injuries, brachial plexus wounds, spinal cord damage, and traumatic brain injuries. Traditional therapeutic modalities, such as ultrasound, fluidotherapy, hot/cold packs, paraffin, electrical stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, splinting, and joint mobilization, are used to help alleviate pain and restore function. C5 OT specializes in the fabrication of custom splints that facilitate tissue healing, prevent deformity, and maximize the functional use of an injured limb (Figures 8 & 9). Appropriate adaptive technology devices are provided to increase patients' function related to both physical and cognitive impairments. Working with other C5 divisions, for example, recreational therapy, we conduct periodic community reentry group activities in public settings to evaluate cognitive, social, and physical capabilities to identify adaptive needs. Recently, we also explored such alternative modalities as the Nintendo Wii (Redmond, Wash) system to challenge our patients' balance, endurance, and cognitive function, as this modality has of late received attention as a useful therapy. [14]

Figure 9. This soldier suffered a wound leaving him with

an inability to grasp objects with his thumb and fingers.

Here, a guitar pick is mounted into a splint; and he is

able to play the guitar again with use of this splint.

Prosthetics

The prosthetics division of the C5 program is staffed by 2 full-time American Board-Certified prosthetists and 1 full time prosthetic technician. Prosthetics supports a growing demand for a unique population of combat and complex injured that have lost a major limb, partial limb, or digit. We specialize in custom prosthetic limbs designed and fabricated for each individual patient. The program aids SMs who have lost limbs in OIF/OEF, SMs with complex accident-related amputations, retired SMs that have completed their care at 1 of the 3 Department of Defense centers (Walter Reed, Brooke Army Medical Center, NMCSD), and/or eligible family members or retirees with accident- or disease-related amputations.

Prosthetics works closely with each division and team member to ensure that the maximum rehabilitation potential is achieved for each patient. In some cases, prosthetics will provide an immediate postoperative prosthesis in the operation room. Our prosthetists also work closely with our PT, OT, and recreational therapy teams to assist with early wound care, prosthetic training, and advanced sports and recreational activities that require unique prosthetic interface materials and components. Each team prosthetist is certified and credentialed in all advanced microprocessor knee, foot, and bionic technologies [7] for lower extremity amputees. Advanced understanding in both socket interface designs and alignments for running and cycling is commonly used to achieve the goals of each patient. Prosthetics also services upper limb amputees with several types of advanced elbow and hand units. Myoelectric, conventional, and cosmetic prosthetic limbs [7] are available for our patients who have experienced an upper limb loss.

The prosthetic facility contains several rooms to design, fabricate, and fit prosthetic limbs. The patient evaluation and casting room has an advanced CAD/CAM computer system called the Biosculptor (Hialeah, Fla). Digital scans of a patient's residual limb are taken, then downloaded and modified on the computer using advanced digital software. A second and more common approach of taking a negative impression of the patient's residual limb is that of using plaster bandage wrap. Capturing the shape of the soft tissue and anatomy gives the prosthetist a true hands-on approach. The next room and stage in the design process are the plaster and modification area. This room is made up of 2 bench stands, a stainless steel sink, and large containers that hold 100 lb of plaster. A lamination and thermoplastics room was designed for fabrication of all upper and lower extremity prosthetics. Here, carbon fiber, plastics, and high-grade aluminum are used in the construction of each limb. A heavy machine room and laboratory make up the final section of the prosthetic facility. All prosthetic adjustments and final alignments are finished in these areas. A variety of tools, such as a drill press and sanders, help deliver a highly advanced prosthesis. The patient's first steps are in our prosthetic facility gait area; through use of an 18-ft parallel bar set for static and dynamic alignments, this is the final process before patients can begin their rehabilitation using their new limb.

Recreational Therapy

The C5 recreational therapy was created as part of the interdisciplinary treatment team supporting the rehabilitation of OIF and OEF veterans that sustained injuries resulting in permanent or long-term disability. Working closely with all of the other rehabilitation team members is essential for the success of this program. The recreational therapist uses a wide variety of experiential learning opportunities that provide an environment and opportunity for patients to discover what new possibilities lie ahead and to potentially redefine their sense of self.

The patient is evaluated as soon as is practical after arriving at C5. During that assessment, medical history and disability information are gathered.

A leisure interest survey is performed assessing past, current, and future leisure interests from 7 categories of activity:social and group

solitary

physical

creative

outdoor

spectator events, and

passive games.Potential barriers to leisure participation are identified. Short-term physical, cognitive, and psychosocial rehabilitation goals and long-term leisure education and recreation participation goals are established. Based on this evaluation, the patient's current condition, and collaboration with the other rehabilitation team members, a rehabilitation plan is developed focusing on those established goals.

Short-term cognitive rehabilitation goals include improving concentration and attention span, memory, problem solving, critical thinking, communication skills, safety awareness, and judgment. Physical rehabilitation goals include improving strength and endurance, fine and gross motor function, balance and proprioception, independent community mobility, and performance of ADLs, with the least restrictive assistive device. Psychosocial rehabilitation goals include improving social skills and interaction, improving confidence and self-esteem, adjustment to disability and/or body image, and reduction of withdrawal.

There are 2 common long-term goals that apply to each C5 patient: the first is to develop and acquire leisure-related skills, attitudes, and knowledge for the establishment of an appropriate leisure lifestyle; the second is to demonstrate leisure independence and personal enjoyment through participation in appropriate leisure opportunities. These objectives are accomplished by ensuring that each patient is aware of available adaptive equipment, available community resources, and the ability to exercise a sense of autonomy by choosing which activities and what levels of participation are appropriate. This provides an occasion for the patient to remain motivated and active through successful participation and the development of a positive and healthy leisure lifestyle.

Our patients have the chance to participate in a wide variety of activities to accomplish these goals, including, but not limited to, snow skiing, snowboarding, dog-sledding, snowmobiling, water skiing, surfing, stand-up paddle boarding, kayaking, whitewater rafting, sailing, fly fishing, deep sea fishing, boating, horseback riding, golf, rock climbing, mountaineering, camping, cycling, swimming, scuba, wheelchair sports, and paralympic sports. Community reentry activities are also scheduled, including outings to restaurants, movies, shopping, the zoo, libraries, parks, and other community venues.

Recreational therapy is unique in the sense that it becomes the clinic and the modality. Patients often have the experience of discovering a new activity that they might never have experienced or reconnecting to a preinjury activity, learning a new way in which to participate. Participation in these activities may elicit the first genuine smile or laugh from some patients since their date of injury; and in some cases, it may lead to a new and exciting vocation. Recreation therapy creates a space and an opening to learn new skills, develop new attitudes, enjoy greater independence, and reduce or eliminate the effects of injury, illness, or disability. Ultimately, it can clarify for the patient the fact that there is much life and fun beyond rehab and that opportunities are boundless.

Chiropractic

Chiropractic services are included in the C5 program. Some C5 patients have received chiropractic care at previous commands, and a few of the challenged warrior-athletes training at the local Olympic Training Center requested chiropractic services within the command. Already included as a benefit through NMCSD, chiropractic care was added as service to the C5 program in February 2008. The chiropractic services of C5 are offered once a week by 1 of NMCSD's 3 chiropractors, who holds an MSEd degree in medical education and is board certified in sports injury care. Approximately 10% of this provider's time is dedicated to C5 activities; the other 90% of his time is dedicated to providing clinical care at an ambulatory clinic at another local military base.

Because of the complexity of C5 patients' injuries, a variety of procedures are used, including joint manipulation techniques, soft tissue mobilization, therapeutic exercise, and education. Education regarding walking, sleep hygiene, wheelchair use, sports activities, and other ADLs is an important part of the care that each patient receives from a biomechanical point of view. To avoid confusing patients or offering conflicting information, patient education is coordinated between the various divisions by the providers reviewing electronic medical records of fellow providers and by speaking with one another.

The doctor of chiropractic uses a typical treatment room that contains an adjusting bench/physical therapy table and computer and has access to the C5 physical therapy gym and outpatient physical therapy treatment area. The predominance of patients referred for chiropractic care have neck and back pain. These areas present common secondary pain problems for patients with amputations and polytrauma. [2, 10] Problems, such as back and neck pain, can interfere with sleep, ambulation, wheelchair use, sports activities, and other personal needs. Often, the location and character of back and neck pain change as patients transition from being sedentary to sitting in a wheelchair, then to being more active and becoming accustomed to using their prostheses.

Many C5 patients referred for chiropractic care have no previous experience with chiropractic services. Considering the severity of their injuries and the mental health issues often associated with severe trauma, attention is given to progress slowly through various therapies as patients gain confidence in the provider and become more comfortable with care. Oftentimes, treatment will commence with gentle forms of mobilization and exercise; and later, high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation may be used when indicated. In some patients seen at C5, such as individuals on anticoagulant therapy, recovering from multiple orthopedic injuries, or apprehensive about being touched, it is possible that high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation may never be used. The objective is to do what is physically, mentally, and emotionally right for the patient in the context of a team approach at the appropriate time.

The integration of chiropractic care as part of an interdisciplinary approach for the management of complex combat casualties until now has never been reported in the literature. With its lack of addiction risk, chiropractic care may be a useful pain management strategy for this population; and it seems to be well liked by patients. Pasquina et al [7] stated that cutting-edge complex injury centers will include therapies that have demonstrated effectiveness in managing the wounded and that these centers should also consider potentially helpful treatment alternatives for our returning combat injured. We look forward to investigating the potential effectiveness of chiropractic care in this environment and reporting results in the future.

Electronic Medical Record

Each patient encounter is recorded via an electronic medical record system. Every credentialed provider has access to each patient's previous encounters, radiology results, medications, laboratory results, and other medical data so that the entire clinical picture can be carefully monitored and considered. All providers are required to document patient encounters in the electronic medical record. The use of this system provides immediate transparency of patient care and assists in enhancing communication between providers. For example, if the chiropractor provides home exercises to a patient and one of the physical therapy assistants needs to know what kind of exercises were assigned, this information can be retrieved quickly with the electronic medical record. This documentation system helps providers avoid overtreating patients or giving conflicting advice. Each entry is viewable not only by NMCSD providers, but all credentialed providers who have access to the system, whether they are in the continental United States or abroad in theater clinics and hospitals.

Discussion

Table 2 To date, C5 has provided musculoskeletal rehabilitation care to approximately 500 patients from the operational theater, Veterans Affairs, other military treatment facilities, and local trauma centers. Of these 500 patients, 58 have had amputations (Table 2). The goal of C5 rehabilitation care is to assist SMs in returning to active duty or transitioning out of military life back into the civilian world. This is a lengthy process, but can be rewarding for all concerned. C5 has returned several SMs to active duty, including 2 who have deployed again to OIF using their prostheses.

Caring for America's modern warriors is both an honor and a privilege, but it can be emotionally and physically taxing for caregivers. It takes a certain amount of fortitude and courage to talk, listen, and feel on a daily basis what our SMs have given and endured. Many rehabilitation providers have limited experience in performing a history and examination on someone who has suffered extensive physical and psychologic injuries of war. Whereas a case of axial low back pain may take 15 to 30 minutes to work up in a typical outpatient clinic, the same problem in the polytrauma or amputee patient may take more than an hour, as some patients may spontaneously recount the events leading to their wounds and some, because of traumatic brain injury, may have lost the social filters necessary to screen out graphic language and stay focused. Adding to the complexity of this environment, our staff often find themselves with family members or friends deployed to current areas of conflict, placing the potential realities of war close to home. One of the challenges we see is caring for our caregivers; Friedemann-Sanchez et al [15] have studied providers of polytrauma care and identified that these caregivers had greater media and political exposure, more emotionally taxing work, and increased workload compared with their previous work settings. Our experience is similar to the reports by Friedemann-Sanchez et al, and we agree that support groups and training are 2 options to mitigate some of the unique stressors associated with working in this environment and with this patient population.

To further contribute to the literature on the unique cases seen at C5, several members of the C5 musculoskeletal rehabilitation team are actively involved in research projects. A case report exemplifying the integrated care of a patient with double amputations after injuries sustained in OIF was presented at the 114th Annual Meeting of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States and is being prepared for publication. Members of the gait analysis laboratory are evaluating rehabilitation techniques and outcomes, working with the orthopedic department to evaluate the functional outcomes of 2 different surgical techniques for transtibial amputation, and are developing a technique to measure the work of walking from gait data, studying a haptic feedback system for amputee gait, and measurements to evaluate the ability to return to active duty. Further collaborative research between the gait analysis laboratory and a local research command, Naval Health Research Center, is being explored to investigate the feasibility of conducting clinical research pertaining to return to duty, balance, and vestibular rehabilitation.

Limitations

The breadth of the entire C5 program is much greater than what can be related in one article. Many valuable services are offered for C5 patients, such as neuropsychologic testing, speech therapy, mental health care, social work, community reintegration, and others. However, it was beyond our scope and feasibility to address all services of C5. As a result, we elected to provide a description of how musculoskeletal rehabilitation is provided at our center in an effort to provide a focused and meaningful discussion that may be useful for other programs managing similar populations. It is difficult, if not impossible, to measure the effectiveness of any one particular therapy for C5 patients because each patient is provided multimodal care. To measure the effectiveness of this program, it will be necessary to look at functional outcomes for the patients involved and consider how each service provided contributes to the overall well-being of the patients, rather than attempt to isolate the effectiveness of one particular therapeutic approach. At the time of this writing, these outcomes were in the process of being developed, but were not yet in use. We hope to share these results in future research studies.

Conclusion

Polytrauma care is complex and requires an interdisciplinary and integrated approach that welcomes innovations to address the multitude of patient needs. In 3 years, NMCSD's C5 program evolved from concept to reality; and the musculoskeletal rehabilitation team has grown in size, as have the services offered. Although much has been done clinically to provide for this population, the effectiveness of some methods and the combined effectiveness of all services provided deserve further investigation. It is our hope that sharing the experience of our musculoskeletal rehabilitation team will assist other centers and add to the small but emerging literature on this topic.

Practical Applications

Musculoskeletal injuries are a common problem for military SMs.

Providing rehabilitation for patients with polytrauma and multiple

orthopedic injuries requires a patient-oriented and

multidisciplinary team approach.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jennifer Town, the C5 Program Director, for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Potter, BK and Scoville, CR.

Amputation is not isolated: an overview of the US Army Amputee Patient

Care Program and associated amputee injuries.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006; 14: S188–S190Clark, ME, Bair, MJ, Buckenmaier, CC, Gironda, RJ, and Walker, RL.

Pain and combat injuries in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom

and Iraqi Freedom: implications for research and practice.

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007; 44: 179–194MacLennan D, Clausen S, Pagel N, Avery JD, Sigford B, Mahowald R.

Developing a polytrauma rehabilitation center: a pioneer experience in building,

staffing, and training.

Rehabil Nurs 2008;33(5):198-204, 213Sayer, NA, Chiros, CE, Sigford, B, Scott, S,

Clothier, B, Pickett, T et al.

Characteristics and rehabilitation outcomes among patients with blast and other

injuries sustained during the global war on terror.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89: 163–170Smurr, LM, Gulick, K, Yancosek, K, and Ganz, O.

Managing the upper extremity amputee: a protocol for success.

J Hand Ther. 2008; 21: 160–175 ([quiz 176])Department of Veterans Affairs.

VHA Directive 1172.01, Polytrauma Rehabilitation Procedures

Veterans Health Administration, Washington (DC); 2013Pasquina, PF, Bryant, PR, Huang, ME, Roberts, TL,

Nelson, VS, and Flood, KM.

Advances in amputee care.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006; 87: S34–S43 ([quiz S44-5])Esquenazi, A.

Amputation rehabilitation and prosthetic restoration.

From surgery to community reintegration.

Disabil Rehabil. 2004; 26: 831–836Ketz AK.

Pain management in the traumatic amputee.

Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2008;20(1):51-7, vi.Ephraim, PL, Wegener, ST, MacKenzie, EJ, Dillingham, TR, and Pezzin, LE.

Phantom pain, residual limb pain, and back pain in amputees:

results of a national survey.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 86: 1910–1919Grabowski, AM and Kram, R.

Effects of velocity and weight support on ground reaction forces and

metabolic power during running.

J Appl Biomech. 2008; 24: 288–297Broglio, SP, Sosnoff, JJ, Rosengren, KS, and McShane, K.

A comparison of balance performance: computerized dynamic posturography and

a random motion platform.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009; 90: 145–150Teyhen, DS, Miltenberger, CE, Deiters, HM, Del Toro, YM,

Pulliam, JN, Childs, JD et al.

The use of ultrasound imaging of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver in

subjects with low back pain.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005; 35: 346–355Hill, CS.

Developing psychomotor skills the Wii way.

Science. 2009; 323: 1169Friedemann-Sanchez, G, Sayer, NA, and Pickett, T.

Provider perspectives on rehabilitation of patients with polytrauma

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 (Jan); 89 (1): 171–178

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 7-09-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |