Maximizing the Effectiveness and

Efficiency of Clinical DocumentationThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

Adapted from: Topics in Clinical Chiropractic 1994; 1 (1): 60–65

Robert D. Mootz, D.C.Special thanks to Aspen Publishers and Robert Mootz, D.C. for permission to reproduce this article, exclusively at Chiro.Org!

In contemporary health care, the adage "you are what you write" has more relevance to chiropractors than ever before. Managed care, integrated and multidisciplinary practice, increased demands for clinical accountability, and medicolegal requirements necessitate extensive and thorough clinical documentation. At the same time, the realities of business and reimbursement constraints demand that any such documentation be as efficient as possible.

The patient chart should accurately reflect clinical thought processes and should document the patient's status — specifically, how the patient has progressed since care was initiated. This aspect of documentation is often neglected, yet in terms of medicolegal, insurance, and quality assurance issues, appropriate charting will serve both doctor and patient in many ways. As the chiropractic profession's acceptance has increased in recent years, so has scrutiny of clinical methods and doctors' records. Benefit determination is often heavily influenced by record review. Most importantly, especially for busy, larger-volume practices and group settings, the chiropractic chart is one of the most useful tools at the doctor's disposal to document and modify care strategies for patients.

A number of standards for recordkeeping exist. [1-5] National standards for quality assurance in certified health plans now mandate reviews to assure quality records in patient charts. [6] These days, many providers are dependent on participation in managed care contracts, which often stipulate documentation and reporting expectations. When second opinions are required or when other doctors review records, several key clinical markers are sought in the patient chart. [7]

"Problem-oriented" patient management and record-keeping have become standard across all health care disciplines. [1,] [4,] [5] That approach is covered here, with special emphasis on and adaptations for chiropractic practice, along with commentary on optimizing its efficiency. Consistency and thoroughness of format, from identification of patient complaints to investigation of the clinical database (history, examination, special diagnostic studies), as well as determination of clinical impression and written care plans, are important components that chiropractors are expected to chart. [1]

To facilitate understanding of the problem-oriented approach, components are discussed and described in a manner erring on the side of thoroughness. In implementation, abbreviations, preprinted forms, and other shortcuts may be tailored to the clinician's preferences and practice. However, it remains key that charting be decipherable by external readers through abbreviation keys and the like.

Patients' conditions change over time. Thus, ongoing treatment programs, as well as patient progress, are subject to modification. Problem-oriented record-keeping provides a concise methodology for implementation of initial charting and maintenance of chiropractic clinical files over the duration of care, be it brief and episodic or of longer term. Numerous advantages to this methodology include being able to map and monitor changes in the patient's condition, thereby documenting effectiveness of treatment. Communication with third parties (insurance carriers, attorneys, and other physicians) is facilitated, as well.

In addition to standard charting practices, the burgeoning interest in outcomes assessment has led to development of numerous pencil-and-paper instruments that can reliably track a patient's health, function, and symptomatic status. [8] By maintaining adequate case records, the doctor of chiropractic is able to stay on top of patient progress and to render the best possible service, while reducing record review and and medicolegal headaches.

CHARTING AS A REFLECTION OF CLINICAL DECISION MAKING

Any efficient means of documenting patient evaluation, care, and progress should be templated on the procedural approach that a practitioner would ordinarily use in case management. Essentially, case management decisions center on mapping out an appropriate diagnostic course and following through with a consistent plan of intervention and monitoring. The chiropractic record should mimic in as many ways as possible the processes and chronology that the DC goes through in real-time clinical decision making.

Not only is this a rational and efficient approach to charting, it also provides for accurate reconstruction of clinical reasoning retrospectively. Increasingly busy doctors are hard-pressed to remember exactly why they approached a situation in the way that they did without the benefit of key notations made at the time of the encounter. A well-organized chart can capture details of the clinical presentation of a given clinical situation and can record the investigative and therapeutic courses of action that have been undertaken. Lloyd et al [4] have commented on the relatively low standard of medical records in general, and numerous chiropractic authors have addressed the issue, as well. [1], [2], [3] With a minimal amount of time, some consistent practice, and well-designed paper work, the DC can maintain high-quality clinical documentation within the time constraints inherent in contemporary practice.

To facilitate an understanding of documentation, a brief review of clinical decision making is useful. Case management has four distinct components common to all health care approaches. Weed [5] originally identified them in a "problem-oriented" fashion, and their educational and clinical usefulness have been thoroughly described. [9] These components are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Components of Case Management

1. Database

History = Subjective (S) part of SOAP Examination Special studies

- Outcomes instruments = Objective (O) part of SOAP

- Laboratory

- Imaging

- Specialist consults

2. Clinical impression

Problem list = Assessment (A) part of SOAP

3. Written plan

- Diagnostic plan (DxP)

- Treatment plan (RxP) = Plan (P) part of SOAP

- Patient education plan (EdP)

4. Case progress

- Routine treatment encounters (mini-SOAP)

- Periodic reevaluation (midi-SOAP)

Database

Initially, the clinician attempts to gather information about the patient and his or her problems. Usually, this starts with taking a history of the present complaint, followed by a review of systems and past history. [10], [11] After the doctor has an adequate picture of the patient's subjective perception of the condition, objective information is obtained by direct examination of the area of complaint and related systems. Initially, and, depending on presenting factors, an appropriate level of physical and/or regional examination may be in order. Examples of comprehensive and efficient chiropractic consultation, history, and examination forms are provided at the end of this chapter.

History and examination findings should narrow the list of possible causes of the patient's complaints. Frequently, one or more different factors or conditions may be contributing to the problem. Special studies, such as laboratory tests and imaging studies (radiograph, computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging scan, scintography, etc.), may be useful to rule in or out various possibilities.

In the past, traditional medical beliefs sometimes placed greater value on the doctor's "objective" perspective but, in fact, patient reports and outcomes tracking can be reliable and valid. [7]Although all patient reports and examination findings may be subject to deliberate falsification, this is not the norm. Rather than assuming the patient's perspective to be biased or unreliable, competent evaluation should include psychosocial assessment and tests such as Waddell' s signs to determine the extent of somatization.

In summary, the database includes the patient's chief complaint, history (present illness, along with past family, clinical, social, and occupational histories), examination, and special studies. The history effectively represents the patient's "subjective" perception of the condition, whereas the examination and special studies represent the clinician's "objective" perspective of the current state of the patient. Clustering and interpreting the findings leads to the next "phase" of management — the clinical impression or diagnosis.

Written Impression

After a reasonable portion of the database is gathered, the doctor formulates a clinical impression or diagnosis. This may be a clear-cut diagnosis or may involve several differential diagnoses. It is important for the initial working impression and any subsequent modifications to be recorded in some accessible fashion in the chart. This second portion of case management serves as the assessment of the patient's condition. Based on this summary of patient status, the doctor develops a clear perspective on what interventions are needed to resolve the patient's problem(s). The impressions and diagnoses will be likely to change over time and, therefore, must be modified. Still, the doctor's thought process needs to be documented chronologically. A problem list can serve to organize a patient's diagnoses and conditions in summary fashion over time. If kept as a cover sheet in or on the patient chart, it is always readily accessible and can be quickly updated when appropriate. A sample problem list (Fig 5) can be found at the end of this chapter.

Written Case Management and Treatment Plan

Once the causes (or possible causes) of a patient's problem have been enumerated, the next phase of case management involves deciding what to do about them. In many situations, doctors are required to preauthorize some procedures through documentation of specific treatment plans, goals, and outcomes. It is obviously most efficient when this information is readily gleaned from existing records, rather than through administrative reporting, requests for additional information, etc. Legible and coherent charting may help to reduce this when clear diagnoses, causation, assessments, and treatment plans are consistent and readily identified in the chart.

In addition, multiple treatment options may need to be recorded. This may include further diagnostic work to monitor progress; clarifying and refining the initial impression; or a therapeutic trial of a particular procedure or set of procedures to see whether the condition responds.

Care plans consist of three basic parts:

Additional diagnostic procedures that may be necessary in caring for the patient.

"Passive" interventions that the doctor may provide for the patient.

"Active" or self-care interventions that patients may be directed to do or to participate in on their own.

The first portion of the written plan is usually the diagnostic plan. A therapeutic trial is frequently the least expensive and least invasive of further diagnostic possibilities. In nonlife-threatening situations, such a trial is often the most prudent diagnostic plan. It is also appropriate when there is minimal difference between available treatment options for various conditions. This is known as the Diagnostic Plan and is abbreviated here as DxP. Obviously, the therapeutic trial may overlap conceptually with other portions of the written plan, but by indicating that a trial of care will be used as a diagnostic tool, the doctor may help minimize the possibility of useless ongoing care.

A second portion of the written plan is the doctor's specific treatment plan. This includes procedures that the clinician or staff will actually be performing on the patient (for instance, spinal adjusting and modalities) and can be referred to as the Treatment Plan, or RxP. Although an oversimplification, things that the doctor does to the patient may be referred to as passive procedures, in that the patient is a "passive" recipient of care during the process.

Lastly, there are things that the patient can do, such as postural and exercise protocols, and lifestyle and dietary modification. This is known as the Education Plan, or EdP. This kind of care involves the active participation of the patient and is often referred to as active care. Many facilities provide classes in spinal and back care, spinal stabilization and exercise training, and work or fitness hardening programs that allow the patient to get into condition and to learn how to maintain pain-free and optimal function over the long term. The sample problem list at the end of the chapter includes space for documenting the various components of the treatment plan for the conditions being addressed.

In summary, on an initial workup of a new patient, the doctor collects a variety of information, consisting of several components. The patient's own perception of his or her situation is gathered in the history (and/or by self-administered instruments) and is traditionally considered "subjective" information. Examination and quantification of patient signs and symptoms provides a doctor's "independent" evaluation and is often termed objective information. These two kinds of information form the patient's database. The doctor then integrates this information to form a diagnosis or impression of the patient's current status. This is often termed the assessment. Finally, based on what is determined to be the patient's problem, a course of action is planned, consisting of further diagnostic procedures, passive care, and active care.

The right side of Table 1 illustrates how these various components of case management integrate to form the acronym SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, and plan). This terminology has become quite standard in chiropractic practice to indicate various types of information found in patient charts. Because the magnitude of data gathering on a patient is usually the greatest during the initial workup, it has been characterized here as a mega-SOAP. [2] The next phase of the clinical process involves implementation of the plan and ongoing evaluation of the patient.

Case Progress

Upon identification of the patient's problems and potential solutions, the next step in case management is the initiation of the plan. This phase of care is known as case progress. In actuality, case progress is a microcosm of the first three phases of management (database, impression, and treatment plans). Normally, the chiropractor will schedule a series of treatments, then will reassess the clinical effectiveness of the procedures used. This creates two kinds of patient encounters, after the initial workup — routine visits and reassessment visits.

The routine patient visit involves briefly rechecking the patient's subjective status at that time, checking various objective chiropractic indicators and any relevant previously positive examination findings, then coming to an assessment of the patient's status on that day. Next, the doctor will proceed to render the appropriate care and to make any modifications in the patient's self-care recommendations. This visit displays the same characteristics of the initial workup but on a smaller scale: database gathering (subjective history, objective evaluation); assessment of patient status; and plan for treatment. This is commonly referred to as SOAPing the patient. [5] Because of the much shorter and more focused nature of a routine encounter, compared with an initial evaluation, the routine care visit can be characterized as a "mini-SOAP."

Routine subjective assessment typically includes updating what the patient has been experiencing since the previous encounter. Anchored pain scales or duration of symptoms represent some quick quantitative approaches that may be worth noting in this section of a SOAP note. Any changes or differences (or lack thereof) should also be indicated.

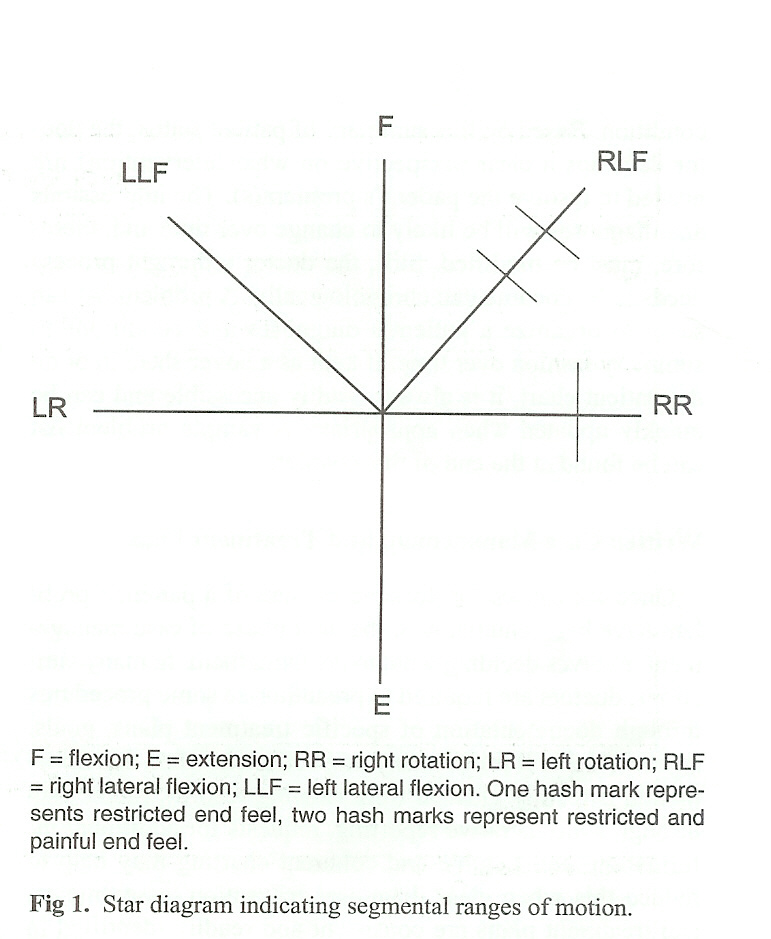

Typically, the objective documentation on routine chiropractic visits might include palpation findings, levels of articular dysfunction or subluxation, location of asymmetry, muscle tightness, etc. A "star" diagram is a commonly used and efficient way to document directions of restricted and painful motion (see Figure 1).

The second kind of post-initial workup patient encounter is a reassessment visit. This is done after a trial of the treatment, or when a new condition arises. The difference between a reassessment visit and a routine visit is that the status of all problems under active care should be thoroughly assessed. Typically, a regional reevaluation of the problem areas is done with the aim of comparing the patient's status at the time of reexamination with that at the time of the original workup for each problem or diagnosis. This also involves SOAPing the patient, except that on reexamination, the original diagnosis and treatment plan may need to be modified. Whereas routine chart entries of regular office calls document patient progress on a visit-to-visit basis, the purpose of a reexamination is to evaluate overall progress on all problems that are not, yet resolved, benchmarking them against their status at the initiation of care.

Although not as detailed as a comprehensive initial workup, a reevaluation is more comprehensive than a routine visit workup and can be thought of as a "midi-SOAP." It is on reexamination visits that the clinician will make a brief notation on the problem/plan list, indicating the date of the reassessment and what has changed. Something as simple as "resolving," "no change — order CBC & UA," or "worse — radiation now to right foot" can be an adequate modification to the problem list. When more detail is needed, the date of the entry directs the reader to the appropriate place in the chart where reassessment was done.

EFFICIENT CHART ORGANIZATION

Patient charts are best correlated with the actual components of case management, as outlined previously. The most useful files are those that separate the various components, allowing simplicity of entry and easy scanning for review. The record should be complete enough to provide the doctor with any information required for subsequent patient care or reporting to outside parties (such as other doctors, insurance companies, and attorneys).

Database

Database forms usually consist of checklists for history and examination, although, in educational settings, a more thorough narrative format is required for initial skill and competency development. Most records tend to be relatively complete in this area. Additional database reports are required for any special studies, as well. This includes laboratory and written radiograph reports that should be part of the chart documentation, as well as any outcomes questionnaires, pain diagrams, etc. are blank sample forms of an initial chiropractic evaluation, a history, and a physical examination form.Figure 2 (Chiropractic Evaluation),

Figure 3 (Comprehensive History) , and

Figure 4 (Physical Exam)

Impression

An easily located record of the diagnoses and changes in patient condition over time is an essential part of the chart. This is most easily accomplished with a "problem list," located as a top sheet on one side of the chart. Some doctors may use the cover of the chart folder for this purpose, but it is important to note that patient confidentiality issues may arise if charts could be in view of non-clinic personnel.

Each identified patient complaint should be described by the nature of the problem. It's chronology, intensity, and exact location should be included as modifiers. Any related contributory or secondary considerations should also be stated.Figure 5 (Example of a Completed Problem List) provides an example of a problem list and treatment plan, with two distinct diagnoses.

Figure 6 (Sample Blank Problem List) provides a sample problem list and plan sheet.

In an actual chart, abbreviations can be used extensively, as long as the abbreviations can be provided for interpretation by others. [3,] [12] The problem list, therefore, serves as a table of contents for the entire chart. It should provide space for three columns: see Figure 5:

The entry index, showing the date that the problem was entered. This will direct the doctor to other similarly dated database/progress entries that have all of the detailed information leading to that diagnosis. This is extremely efficient in looking for exam findings to support a diagnosis when writing a narrative or workers' compensation report.

The problem itself, as described previously. It is often helpful to include any ICD code numbers here, as well, for insurance purposes.

The modification index, showing dates and content of subsequent changes in the condition. This provides directions to the progress entries of brief reexaminations and to more detailed information about what changes are occurring with the problem.

Figure 5 (Example of a Completed Problem List)

Entry Date

and

Problem #

Problem and Plan

Modifications

5/1/88

1

Acute mild cervical sprain/strain w/myosilis & C7 dermatome numbness 5/21/88 Improving

6/30/88 ResolvedDxP: none

RxP: cryotherapy; soft tissue 3x/1 wk then SMT 3x/wk for 2 wks

EdP: home alternate ice & heat daily

cervical passive ROM stretching5/21/88 SMT 2x2

6/7/88 SMT 1x3

6/30/88 Discharged5/1/88

2

Mild hypertension

DxP: monitor BP 1 x/wk for 4 weeks

RxP: if no change refer to family MD for evaluation and Rx

EdP: decrease fat/salt intake increase cardiovascular exercise6/1/88 Resolved

Fig 5. Example of a problem list entry with written plan

Whenever a reexamination is performed or when there is a significant change in patient status, a brief entry of one or two words and the date of the change should be entered in the modifications column. When reviewing the chart at a later date, one need only refer to the progress note entry on that date to find all the details regarding the change. This is much easier then attempting to recall details from memory and faster than reviewing the entire record to get the information needed for an insurance report or a patient inquiry.

Written Plan

Before the doctor begins treatment, he or she should develop and document a plan intended to address all of the problems currently in the problem list. This can be recorded below each problem on the same list, as illustrated in Figure 6 (Sample Blank Problem List). The written plan's three components include a diagnostic plan, treatment plan, and education plan. Each contains a brief summary of what is to be done, how often, and for how long. In this way, it is simple to assess the progress of the plan originally agreed upon with the patient and how well the patient has complied with it. It is extremely useful to have a clearly recorded map of where the patient was initially, what the initial course of action was, and how it worked. The problem-oriented method of recordkeeping addresses these needs well. [13] A combination problem list and plan sheet efficiently summarizes the workup and progress in an easy-to-use manner. [5] Space for the written treatment plan is included in the sample problem list form in Figure 6.

Progress Notes

Recording the patient's progress from visit to visit can be done thoroughly, yet quickly, by including all four parts of SOAP. Ideally, each problem should be recorded separately, making it easier to scan the records at a later date Figure 7 (Sample of Completed SOAP Note). This is easiest if records are jotted down after the actual patient work-up is performed. If charting concurrently with actual patient work-up and care, this organizational approach becomes somewhat difficult. In the latter situation, recording all problems numerically under each SOAP heading tends to be easier but is harder to scan at a later time.

Figure 7

DATE & PROBLEM # ADDRESSED

(from entry index of problem list)

SOAP Entry 5/16/88

1

S: Pain decreases since last visit but more morning stiffness

O: Decreased R cervical rotation; Positive foramina compression: neutral; R para-cervical muscle spasm

A: Decreasing inflammation, increasing muscle tension

P: Initiate cervico-thoracic adjusting

C-2 PRI-L

T-1 PLS2

S: None

O: BP L: 152/88 R: 146/86

A: No change

P: Continue to monitor

Fig 7. Sample of a routine "SOAP" progress note entry

The date of the visit should be first, followed by the problem number from the entry index of the problem list. Included next are the subjective, objective, assessment, and plan entries. These need be only brief, abbreviated comments but should be thorough enough to provide any information that may be required at a subsequent visit or chart review. Many kinds of mechanical assessment recording procedures are available and can be used to speed up the process of record entry. The use of star diagrams to indicate directions of restricted motion is an example of one such notation. [14]

As mentioned previously, the two kinds of follow-up visits are routine patient visits and reexaminations. The first is simply recorded in patient progress notes, whereas the reexaminations should somehow stand out from regular progress entries. This is often done on a new examination form or on a differently colored progress note page. In either situation, reexams can then be easily located by date. Reexamination is a good time to return to the problem list and make a note of how the diagnosis and treatment have changed over time ( see entries in the modifications column in Figure 5 ).

Pros and Cons of a Problem-Oriented Approach

There are two significant disadvantages involved with problem-oriented recordkeeping. First, it takes practice to learn to use it effectively. This alone can inhibit many from adopting such a system, especially when it entails modifying existing charts. The second drawback is that it requires a little extra time during the day for chart entries. There is minimal difference in managing the database information; however, keeping up a problem list may require a few extra minutes following reexaminations. The routine patient entries also involve a bit more time and organization, although in trained hands, this rarely need be more than a minute per patient.

The increased investment in time is usually more than made up when writing insurance or narrative reports, or when testifying in court. Organized charts decrease the amount of time and effort required for such preparation. By far the most important reason for such organization and follow-up in recordkeeping is that the doctor stays on top of patient care. Few of us are capable of remembering all the details of patients' clinical findings and our interpretation of them at the time (particularly months or years later, when a record or report is requested).

Complete charts can be of great use when interacting with other professionals on the patient's behalf. Interactions with other physicians are facilitated. [15,], [16] As chiropractic begins to interact more with the health care delivery system, proper patient documentation works to the chiropractor's advantage. [3,], [11,], [17] Having a complete and understandable chart in hand for review prior to walking in to continue care with a patient allows the clinician to become refamiliarized with the patient's condition (e.g., which procedure is most effective, which is not, which leg is involved, etc.). This conveys an image of a knowledgeable, interested, and caring doctor. The image is an accurate one, because the doctor who takes the extra effort and makes the time to monitor and review each and every patient as an individual truly is a caring doctor.

Striving for Efficiency

Today's reimbursement limitations often preclude extensive luxury in spending time on detailed chart notations. It is essential that records be easy to maintain and not require extensive writing. Dictation remains frequently utilized in medical practice; however, chiropractors predominantly make chart notations by hand. Dictation has the advantage of allowing the doctor to record thoughts more completely, but the narrative format of such chart entries can be inefficient for reviewing at a later date. When dictating, the same organization associated with problem-oriented recordkeeping should be used. Following the SOAP model is important; however, one need not dictate "S," "O," "A," "P" before each entry.

An advantage of written records is that these components can be preprinted on the pages to serve as an ongoing reminder to include an entry for each dimension of the clinical management process. Abbreviations are essential, but they need to be standardized and used consistently by all clinic staff. It is essential to have a key of abbreviations used in the practice that can be referred to or supplied for third-party review. Some jurisdictions even have laws or policies requiring this. The blank forms included in Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4 have the common notations preprinted on them. This is a good idea,both for future reference and third-party review; it is also useful for the doctor to always have the usual abbreviations retrievable when entries are being made. Charts on the wall and at the clinician's desk also work well.

Some common progress note entries can be very concisely noted. For example, using N/C to designate "no change," an up-arrow to represent "increased," and a down-arrow for "decreased" can speed notation. Use abbreviations that make intuitive sense and avoid nonstandard terms whenever possible. For history taking, there are many preprinted forms that patients can fill out to save doctors time. If these are used, it is important to be sure that the patient's answers are reviewed and discussed with the patient. Any clinically meaningful information should be noted in the margins by the doctor or recorded in a SOAP-style note on a consultation or progress entry sheet.

There is a number of strategies that may help keep patient flow running smoothly. Basic notations at the time of the patient visit can be expanded in dictation or at a dedicated time during breaks, lunch hour, and/or before leaving for the day. It is important to make such entries as close to the time of the patient encounter as possible, and always on the same day. Updating problem lists and treatment plans is the kind of thing that lends itself to sitting down at a break unhindered and reviewing the chart, checking for new or forgotten complaints and the like.

Although problem-oriented charting has been taught in all accredited colleges for a many years, in practice, charts are maintained according to the doctor's customary practice. Accurate reflection of the clinical management and decision-making process may seem irrelevant or burdensome until a medicolegal action occurs, or an insurance company review denying payment is upheld. The courts and review communities often default to a position that if it isn't documented, it didn't occur. Although defensive reasons such as these may be persuasive enough to motivate better recordkeeping, the real importance is in quality of care.

Memories fade over time. Early in my career, as my practice grew and I found myself unable to remember all of the details about a given patient from a week or two earlier, I discovered the importance of careful charting. A patient with lower extremity problems had returned, and I spent an entire visit doing muscle work on the right leg. With a full waiting room and hurried schedule, I got ready to leave when the patient asked why I worked on the other leg and why I wasn't addressing the problem side. Although my history form showed it to be the left leg, I had no problem list and had never recorded which leg was worked on in the recent progress note entries on the top of the chart. Although this is a minor incident, this illustrates how good records have clinical meaning, as well.

How long care goes on without demonstrable progress can be a function of good records. Temporary disability certification from work, confounding diagnoses, and retrieval of precisely "that adjustment you gave last month that really did the trick" are other real-time clinical management examples that may be enhanced by good recordkeeping. By organizing clinical records according to the decision strategies made, and tracking interventions and progress, based on clinically meaningful elements of care, better care can be delivered. A little time invested in consistent and adequately detailed charting can yield huge savings in future report writing and in reconstruction of a management decision for payers or medicolegal settings. Most importantly, it can help enhance care.

REFERENCES:

Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Peterson D.

Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters

Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1992: 95–106

Mootz RD.

Maximizing the Effectiveness of Clinical Documentation

Topics in Clinical Chiropractic 1994; 1 (1): 60–65

Baird R.

Health Record Documentation: Charting Guidelines.

Dig Chiro Econ Jul/Aug 1981: 32–33

Lloyd G, Wyn-Pugh E, Mcintyre N.

The Problem Oriented Medical Record and its Educational Implications

Med Educ 1976; 10: 143–153

Weed L.

Medical Records, Medical Education and Patient Care

Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University Press; 1969

Martin R, ed.

Reviewer Guidelines for Accreditation of Managed Care Organizations

Washington, DC: National Organization for Quality Assurance; 1993

Sutton M, McMillin AD.

Documentation and Peer Review Issues in Trauma Management.

Top Clin Chiro 1998; 5 (3): 1–9

Vernon H.

Pain and Disability Questionnaires in Chiropractic Rehabilitation

In: Liebenson C, ed. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner's Manual.

Baltimore,MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1996

Cutler P.

Problem Solving in Clinical Medicine

Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1985

Bates B. A

Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Co.; 1987

Wyatt LH.

Handbook of Clinical Chiropractic

Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1992: 5–23

Hansen DT, Sollicito PC:

Standard chart abbreviations in chiropractic practice.

J Chiro Technique 1991; 3 (2): 96–103

Hurst J, Walker H.

The Problem Oriented System

Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1972

Grieve G.

Common Vertebral Joint Problems

Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1981: 435

Baird R.

Obtaining Health Record Information.

Dig Chiro Econ Nov/Dec 1981; 137–138

Mootz R.

Interprofessional Referral Protocol.

Today's Chiro Sept/Oct 1987; 37–39

Kranz K.

Chiropractic and Hospital Privileges Protocol

International Chiropractic Association; 1987

Return to ChiroZINE

Return to SOAP NOTES

Return to DOCUMENTATION

Since 1–16–2003

Updated 7-09-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |