Attenuation Effect of Spinal Manipulation on

Neuropathic and Postoperative Pain Through

Activating Endogenous Anti-Inflammatory

Cytokine Interleukin 10 in Rat Spinal CordThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 42–53 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Xue-Jun Song, MD, PhD, Zhi-Jiang Huang, PhD, William B. Song, Xue-Song Song, MD, PhD, Arlan F. Fuhr, DC, Anthony L. Rosner, PhD, Harrison Ndtan, PhD, Ronald L. Rupert, DC

Parker University,

Parker Research Institute,

Dallas, TX

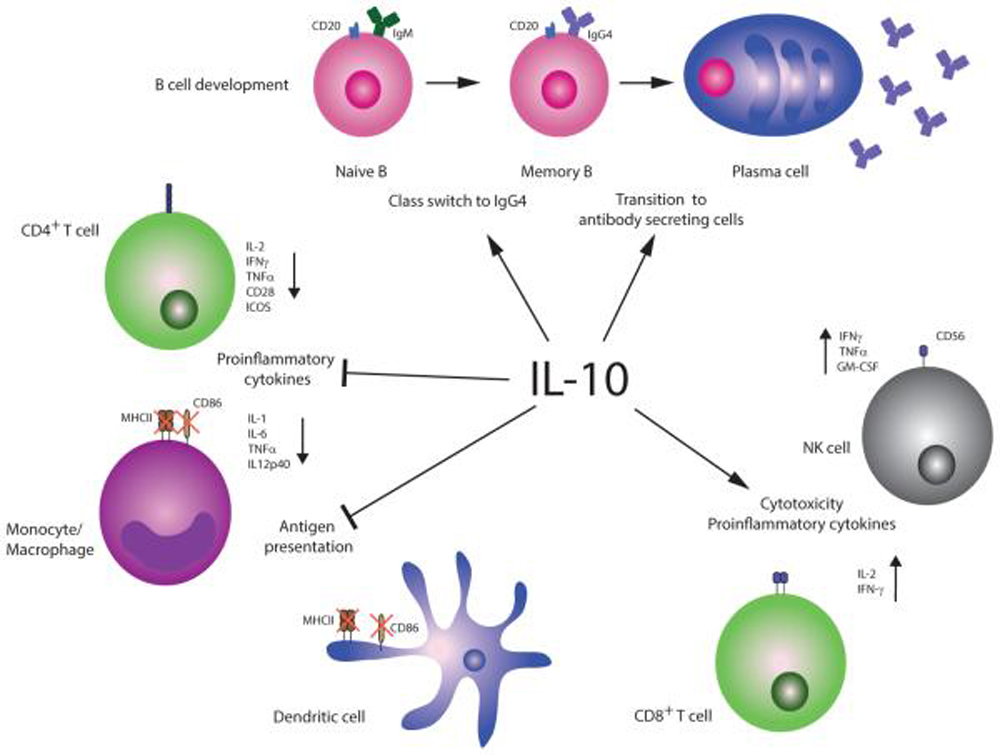

FROM: Cytokine 2015Objectives: The purpose of this study was to investigate roles of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL) 10 and the proinflammatory cytokin, es IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in spinal manipulation-induced analgesic effects of neuropathic and postoperative pain.

Methods: Neuropathic and postoperative pain were mimicked by chronic compression of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) (CCD) and decompression (de-CCD) in adult, male, Sprague-Dawley rats. Behavioral pain after CCD and de-CCD was determined by the increased thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity of the affected hindpaw. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiological recordings, immunohistochemistry, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were used to examine the neural inflammation, neural excitability, and expression of c-Fos and PKC as well as levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10 in blood plasma, DRG, or the spinal cord. We used the activator adjusting instrument, a chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy tool, to deliver force to the spinous processes of L5 and L6.

Results: After CCD and de-CCD treatments, the animals exhibited behavioral and neurochemical signs of neuropathic pain manifested as mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, DRG inflammation, DRG neuron hyperexcitability, induction of c-Fos, and the increased expression of PKCγ in the spinal cord as well as increased level of IL-1β and TNF-α in DRG and the spinal cord. Repetitive Activator-assisted spinal manipulative therapy significantly reduced simulated neuropathic and postoperative pain, inhibited or reversed the neurochemical alterations, and increased the anti-inflammatory IL-10 in the spinal cord.

Conclusion: These findings show that spinal manipulation may activate the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord and thus has the potential to alleviate neuropathic and postoperative pain.

Keywords: Ganglia; Interleukin-10; Interleukin-1beta; Nervous System; Pain; Spinal; Spinal manipulation; Trauma.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Injury and inflammation to the nerve and tissues within or adjacent to the lumbar intervertebral foramen (IVF) can cause a series of pathologic changes, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic low back pain. [1–6] After injury or inflammation, chemical factors (eg, cytokines, nerve growth factors, inflammatory mediators) release, activate, or change the properties of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons within the IVF and spinal dorsal horn neurons. These changes may contribute to chronic pain. [4–11] To better understand the mechanisms of low back pain due to nerve injury and IVF inflammation, we previously developed an animal model of chronic compression of DRG (CCD) [4, 12] and an IVF inflammation model produced by in vivo delivery of inflammatory mediators into the IVF at L5. [13–15] Rats with CCD or IVF inflammation at L4 and/or L5 exhibited measurable pain and hyperalgesia, and the affected DRG neurons became more excitable. Mechanisms underlying chronic pain remain elusive, and the effective clinical approaches for reliving chronic pain are very limited.

Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) has been recognized as an effective approach for reliving certain chronic pain and used for treating patients with chronic pain syndromes such as low back pain. [16–18] Mechanisms underlying the clinical effects of SMT are poorly understood but are thought to be related to mechanical, neurophysiologic, and reflexogenic processes. [16–20] In addition to traditional manual SMT, instruments such as the activator adjusting instrument (AAI) have been used to produce spinal mobilization. [21] The AAI was developed to precisely control the speed, force, and direction of the adjustive thrust to produce a safe, reliable, and controlled force for manipulation of osseous spinal structures. [22, 23] Activator evolved in response to currently knowledge in biomechanical and neurophysiologic categories of investigation. [21, 24, 25] We have previously demonstrated the treatment effects of SMT as performed using the AAI (Activator-assisted spinal manipulative therapy [ASMT]) on pain and hyperalgesia produced by DRG inflammation using the IVF inflammation model in adult rats with outcomes being assessed through behavioral, electrophysiological, pathologic, molecular biological approaches. [15] However, the mechanisms underlying the ASMT-induced analgesic effects remain unknown.

The purpose of this study was to examine the possible mechanisms that may underlie ASMT-induced analgesic effect using a small animal model of CCD and relief of CCD (decompression of CCD [de-CCD]). This study investigated if repetitive ASMT could suppress neuropathic pain after CCD and the postoperative pain after de-CCD, reduce the increased excitability of CCD and de-CCD DRG neurons, attenuate the DRG inflammation, and inhibit induction of c-Fos and expression of PKC in the spinal dorsal horn.

Methods

Animals

All experimental procedures were conducted in concordance with the recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain and the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee, Parker University Research Institute. Adult, male, Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g weight at start of the experiment, n = 96) were used in this study. They were housed in groups of 4 to 5 in 40 × 60 × 30 cm plastic cages with soft bedding and free access to food and water under a 12–/12-hour day/night cycle. The rats were kept 3 to 5 days under these conditions before and up to 28 to 35 days for some animals after surgery. All surgeries were done under anesthesia induced by sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection, supplemented as necessary).

Models of CCD and de-CCD

The CCD was mimicked by surgically implanting a stainless steel rod unilaterally into the intervertebral foramen at L4 and L5. The procedure was modified from what we have previously described.12 In brief, 48 rats were anesthetized, and a midline incision was made from L4 to L6. On the left side, the paraspinal muscles were separated from the mammillary process and the transverse process, and the L4 and L5 IVF was exposed. A fine, sharp, stainless steel needle, 0.4 mm in diameter with a right angle to limit penetration, was inserted approximately 4 mm into the IVF at L4 and L5, at a rostral direction at an angle of approximately 30° to 40° to the dorsal mid line and –10° to –15° to the vertebral horizontal line. Once the needle was withdrawn, a stainless steel rod, L shaped, 4 mm in length and 0.6 mm in diameter, was implanted into the IVFs. The insertion was guided by the mammillary process and the transverse process and oriented as described for the needle. As the rod was moved over the ganglion, the ipsilateral hind leg muscles typically exhibited 1 or 2 slight twitches. After the rods were in place, the muscle and skin layers were sutured.

We observed pain behavioral changes as well as the accompanied pathologic, cellular, molecular biological changes after relief of DRG compression, that, decompression of CCD (de-CCD) (n = 24 of 48 CCD rats), which was mimicked by withdrawing the previously inserted rods (de-CCD). The protocol of de-CCD was similar to that we have described. [4] The rats that previously received CCD were again anesthetized, the paraspinal muscles separated, and L4 and L5 IVF exposed. We carefully found and examined the location of the rod previously implanted. As the rod was gently touched, the ipsilateral hind leg muscles exhibited slight twitches as well. The rod was then carefully withdrawn, and the wound was sutured. The rod was withdrawn from 24 rats on the 10th day after surgery. We presumed that IVF volume reduction and DRG compression induced by a rod insertion were restored and relieved, respectively, after the rod withdrawal. Surgical sham control (Sham) was performed in a separate 24 rats. The surgical procedure was identical to that described in CCD model but without needle stick or rod insertion. An oral antibiotic, augmentin, was administered in the drinking water for each rat (7.52 g in 500 mL) after surgery for 7 days.

Activator-Assisted Spinal Manipulative Therapy

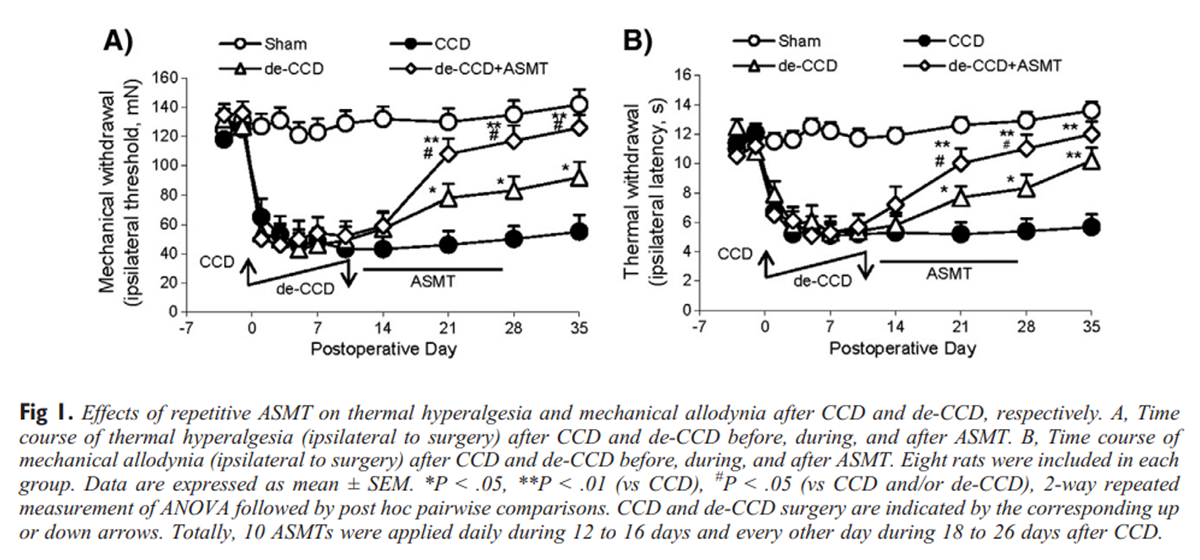

Figure 1

Figure 6 The AAI, delivers short-duration (<0.1 ms) mechanical force, manually assisted spinal manipulative thrusts. The force was applied to the spinous process of L5 and L6. The ASMT with Activator III (kindly provided by Allan Fuhr at the Activator International LTD, Phoenix, AZ) was applied at a rostral direction at an angle of approximately 40° to 50° to the vertebral horizontal line. [15] A series of 10 ASMT was initiated 2 days after DRG decompression (de-CCD) on the 10th day after CCD surgery and subsequently applied daily for consecutive 5 days (12–16 days) and every other day for another 5 ASMT, the last ASMT was on the 26th day after surgery, that is, 14 days after de-CCD. Each ASMT included a single application of the AAI to the spinous process of the L5 and L6 vertebrae, respectively. The spinous process of the L5 and L6 vertebrae formed the tail side of the L4 and L5 foremen. Forces of application are reproducibly determined with discrete settings of a dial mounted on the instrument. Two different force settings, setting 1 and setting 2, were used. In the following description, the ASMTs were named as ASMT-1 and ASMT-2 representing the manipulation force setting at 1 and 2, respectively, whereas the other parameters in the 2 protocols were kept the same. Because ASMT-1 and ASMT-2 were proved to be producing similar analgesic effect on the pain after de-CCD as shown in Figures 1 and 6, ASMT-1 was abbreviated as ASMT and used for the studies described in parts 1 to 5 in Results.

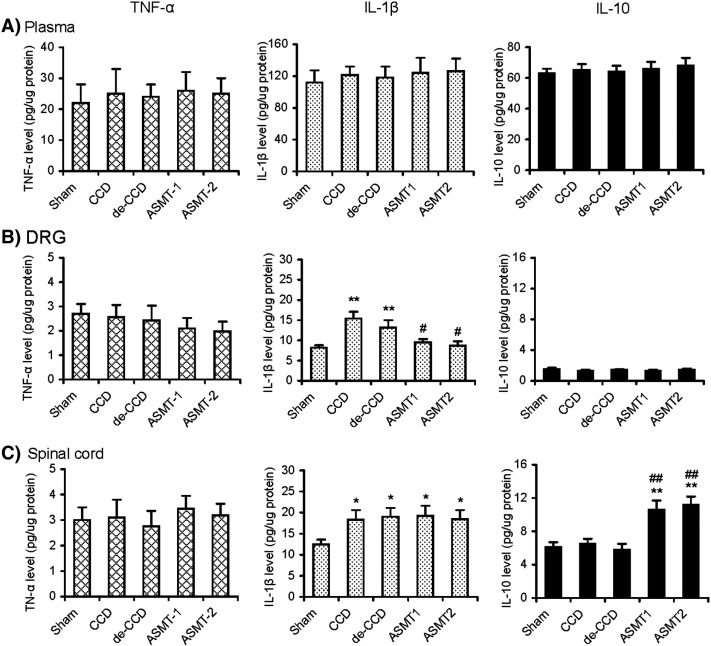

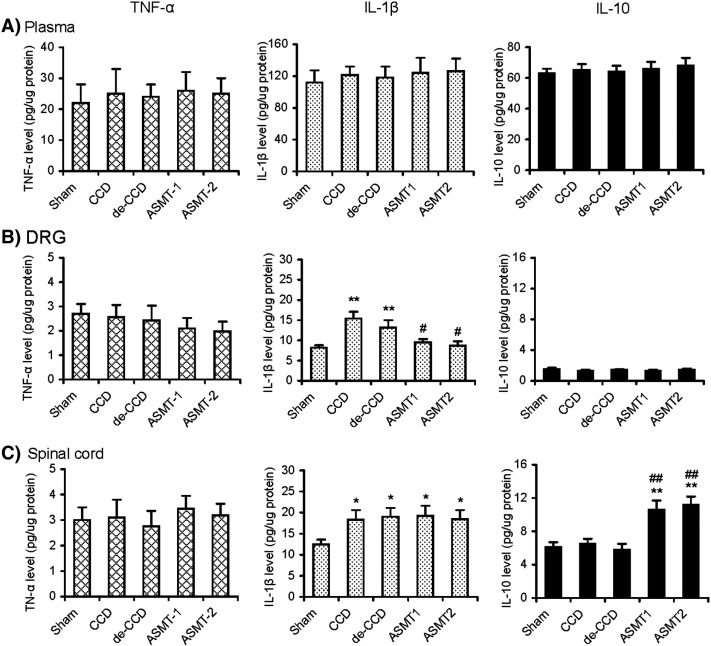

Fig 6. Effects of repetitive ASMT on expression of cytokines IL-1b, TNF-a, and IL-10 in plasma, DRG, and the spinal cord after Sham, CCD, de-CCD, and de-CCD with ASMT, respectively. Activator-assisted spinal manipulative therapy was applied with 2 different forces at Activator setting 1 (ASMT-1) and 2 (ASMT-2). Levels of the cytokines in the plasma, DRG, and spinal cord were determined by specific ELISA-based kits. Six rats were included in each of the 5 groups. *P b .05, **P b .01 (vs Sham), # P b .05, ##P b .01 (vs CCD or de-CCD)

Assessment of Mechanical Allodynia and Thermal Hyperalgesia

The rats were tested on each of 2 successive days before surgery. After surgery, the animals were inspected every 1 or 2 days during the first 14 postoperative days and at weekly intervals thereafter. For general observation, each rats was placed on a table, and notes were made on the animal's gait and the posture of each hindpaw and the conditions of the hindpaw skin. The evoked painful behaviors after CCD or de-CCD were manifested as mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. Mechanical allodynia was determined by measuring incidence of foot withdrawal in response to mechanical indentation of the plantar surface of each hind paw with a sharp, cylindrical probe with a uniform tip diameter of approximately 0.2 mm provided by an Electro Von Frey (ALMEMO 2390-5 Anesthesiometer; IITC Life Science, Inc, Woodland Hills, CA). The probe was applied to 6 designated loci distributed over the plantar surface of the foot. The minimal force (in grams) that induced paw withdrawal was read off the display. Threshold of mechanical withdrawal in each animal was calculated by averaging the 6 readings, and the force was converted into millinewtons (mN). Thermal hyperalgesia was assessed by measuring foot withdrawal latency to heat stimulation. An analgesia meter (IITC Model 336 Analgesia Meter, Series 8; IITC Life Science, Inc) was used to provide a heat source.

In brief, each animal was placed in a box containing a smooth, temperature-controlled glass floor. The heat source was focused on a portion of the hind paw, which was flush against the glass, and a radiant thermal stimulus was delivered to that site. The stimulus shut off when the hind paw moved (or after 20 seconds to prevent tissue damage). The intensity of the heat stimulus was maintained constant throughout all experiments. The elicited paw movement occurred at latency between 9 and 15 seconds in control animals. Thermal stimuli were delivered 3 times to each hind paw at 5– to 6–minute intervals. For the results expressing mechanical allodynia or thermal hyperalgesia, the values are mean of ipsilateral feet. These protocols used for determining the pain-related behaviors were similar to those we have previously described. [4, 12, 15, 26, 27]

Excised, Intact In Vitro Ganglion Preparation

This preparation allows us to test DRG neurons while still in place in excised ganglia. The protocol was the same as that we have described previously. [11, 28–31] On the 28th day after surgery, rats in groups of Sham, CCD, and de-CCD (18 days after de-CCD and 2 days after the last ASMT) (n = 3 rats in each group) received surgery again under anesthesia; a laminectomy was performed; and the L4 and/or L5 DRGs with attached sciatic nerve and the dorsal roots were removed and placed in 35–mm Petri dishes containing ice-cold, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid consisting of (in millimoles per liter) 140 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 4.5 HEPES, 5.5 HEPES-Na, and 10 glucose (pH 7.3). The perineurium and epineurium were peeled off, and the attached sciatic nerve and dorsal roots were transected adjacent to the ganglion. The intact ganglion was treated with collagenase (type P, 1 mg/mL; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for 30 minutes at 35°C and then incubated at room temperature for electrophysiological recordings.

Whole-Cell Current Clamp Recordings

To test excitability of the DRG neurons, whole-cell current and voltage clamp recordings were made with an Axopatch-200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) in the DRG neurons from the intact ganglion preparations. The protocols were similar to that we have previously described. [28–30] Dorsal root ganglion cells were visualized under differential interference contrast in the microscope, and the cell soma was classified visually by the diameter of its soma as small (≤30 µm), medium (31–49 µm), or large (≥50 µm). In this study, we recorded only the small DRG neurons, which are recognized as the nociceptive neurons. Glass electrodes were fabricated with a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (P-97; Sutter instruments, Novato, CA). Electrode impedance was 3 to 5 MΩ when filled with saline containing (in millimoles per liter) 120 K+–gluconate, 20 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 11 ethyleneglycol-bis-(β-aminoethyl-ether) N,N,N′,N′,-tetraacetic acid, 2 Mg-ATP, and 10 HEPES-K (pH 7.2; osmolarity, 290–300 mOsm). Electrode position was controlled by a 3–dimensional hydraulic micromanipulator (MHW-3; Narishige, Cary, NC). When the electrode tip touched the cell membrane, gentle suction was applied to form a tight seal (serial resistance >2 GΩ). Under –70 mV command voltage, additional suction was applied to rupture the cell membrane. After obtaining the whole-cell mode, the recording was switched to current clamping mode, and the resting membrane potential (RMP) was recorded.

All the DRG cells accepted for analysis had an RMP of –45 mV or more negative. To compare the excitability of the DRG neurons, we examined the RMP, action potential (AP) current threshold (APCT), and repetitive discharges evoked by a standardized intracellular depolarizing current. The RMP was taken 2 to 3 minutes after a stable recording was first obtained. Action potential current threshold was defined as the minimum current required evoking an action potential by delivering intracellular currents from –0.1 to 0.7 nA (50–ms pulses) in increments of 0.05 nA. The whole-cell input capacitance (Cin) was calculated by integration of the capacity transient evoked by a 10–mV pulse in voltage clamp mode. Repetitive discharges were measured by counting the spikes evoked by 1000–ms, intracellular pulses of depolarizing current normalized to 2.5 times APCT. All electrophysiological recordings and data analyses were conducted by experimenters blind to previous treatment of the cells.

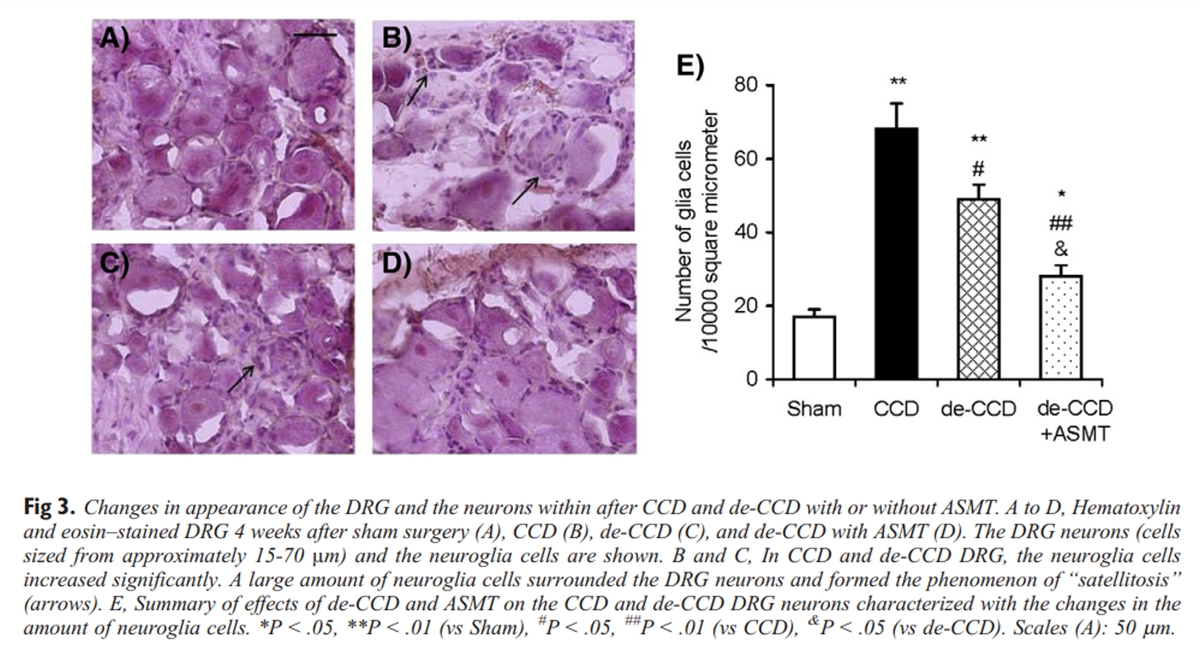

Pathologic Studies

On the 28th day after surgery (ie, 18 days after de-CCD and 2 days after the last of the total 10 ASMT), the DRGs were taken from rats that previously received CCD, de-CCD, or sham surgery. The ipsilateral L4 and L5 DRGs were removed from the rats (n = 12) that previously received sham surgery, CCD, and de-CCD with or without ASMT (3 in each of the 4 groups) and were anesthetized and perfused with 100 mL of heparinized saline followed by 400–mL 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer. The ganglia were postfixed in the same fixative for 3 hours and then immersed in 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Frozen tissues were sectioned (thickness, 15 µm; Leica 1850) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. We chose 4 (second, fourth, sixth, and eighth) of the total 10 sections from the layer of cells (~200 µm) in each ganglion to do further microscope analysis of the neuroglia cells. Four grid areas were chosen from within each section. Each grid area (4 cm2 under ×10 microscope) was used to count the neuroglia cells located on the surface of the sections and could be identified under higher magnification (×40). The counts obtained from these sampling boxes were determined and represent the number of cells per unit of the structure of interest. Finally, the data were calculated and converted into the numbers of neuroglia cells in unit of 1000 µm2 and expressed in the figure in the Results.

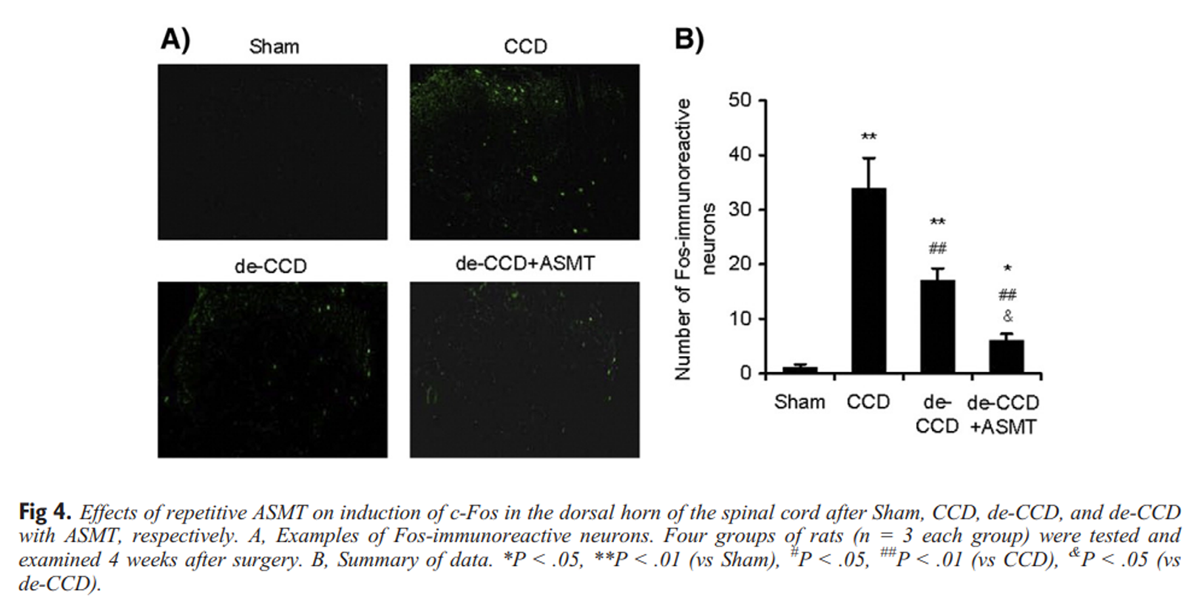

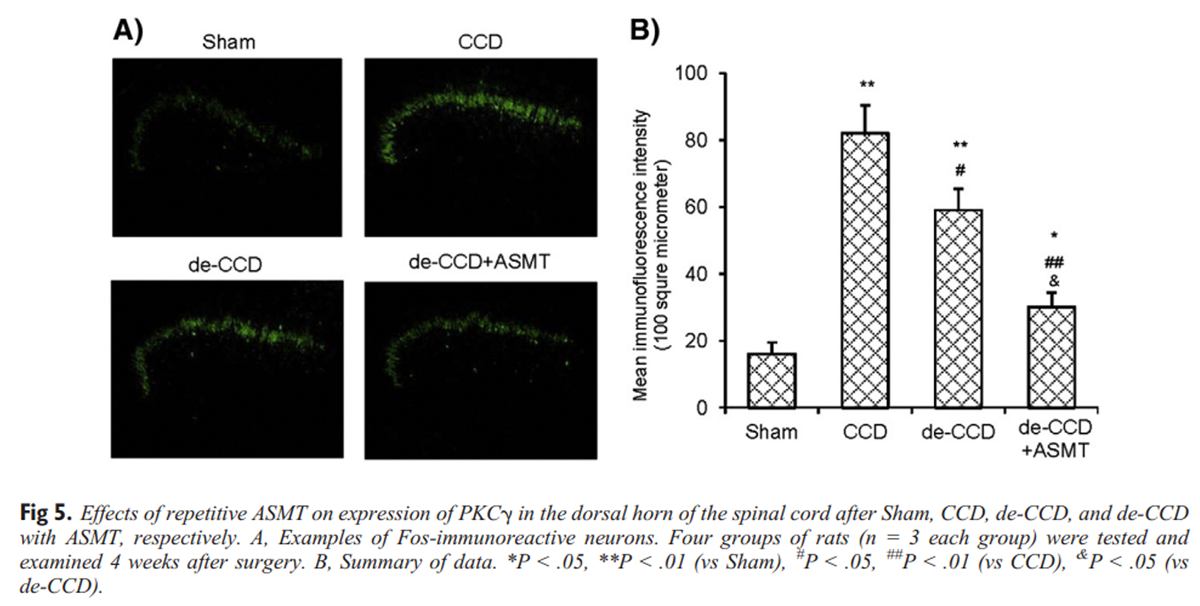

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence Staining of c-Fos and PKCγ in the Spinal Cord

On the 28th day after surgery, that is, 18 days after de-CCD and 2 days after the last of the total 10 ASMTs, a total of 16 rats that previously received sham surgery, CCD, and de-CCD with or without ASMT (4 in each of the 4 groups) were deeply anesthetized and perfused transcardiacally with 0.9% saline and followed by 4% formaldehyde for immunohistochemical studies. The L3–L6 spinal cord segments (targeting on L4–L5, which in CCD group was previously compressed and then decompression in de-CCD group) were removed and postfixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight. In brief, mice lumbar segment of the spinal cord was dissected out and postfixed, and then the embedded blocks were sectioned (10 µm thick). Sections from each group (5 mice in each group) were incubated with rabbit anti–c-Fos polyclonal antibody (1:100) or rabbit anti-PKCγ polyclonal antibody (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit IgG (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Inc, Burlingame, CA) was used as an isotype control. The morphologic details of the immunofluorescence staining on spinal cord were studied under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51WI; Olympus America, Inc, Melville, NY). Images were randomly coded and transferred to a computer for further analysis. Fos-immunoreactive neurons were counted in blind fashion. The number of Fos-like immunoreactive neurons in the dorsal horn (laminae I–VI) of the spinal cord was determined by averaging the counts made in 20 spinal cord sections (L4–L5) for each group. To obtain quantitative measurements of PKCγ immunofluorescence, 15 to 20 fields covering the entire dorsal horn in each group were evaluated and photographed at the same exposure time to generate the raw data. Fluorescence intensities of the different groups were analyzed using MicroSuite image analysis software (Olympus America, Inc). The average green fluorescence intensity of each pixel was normalized to the background intensity in the same image.

Determination of Cytokines in Blood, DRG, and the Spinal Cord

On the 28th day after surgery, that is, 18 days after de-CCD and 2 days after the last of the total 10 ASMTs, a total of 24 rats that previously received sham surgery, CCD, and de-CCD with or without ASMT (6 in each of the 4 groups) were sacrificed under anesthesia for collecting blood as well as DRG and the spinal cord tissues for detecting levels of cytokines tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL) 1β, and IL-10. Blood (2–3 mL) was drawn from left ventricle by vacuum pick blood vessels immediately before the animals under deep anesthesia were sacrificed for further studies. The protocols for taking DRG and the spinal cord were the same as that described in the paragraphs of the intact in vitro ganglion preparation without collagenase treatment and the paragraph of immunohistochemistry. Levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 in the blood and nerve tissues DRG and the spinal cord were determined by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based kits according to the manufacturer's protocol. Proteins were quantified using the samples for ELISA-based analysis. Determination of all the 3 cytokines was performed in duplicate serial dilutions.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in mean mechanical threshold and thermal withdrawal latency over time were tested with 2–way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) followed by post hoc paired comparisons. Between-animal group comparison of the score obtained on the given experimental day was with Mann-Whitney U test. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett tests was used to test the hypothesis that changes in groups of CCD and de-CCD were significantly different from the corresponding groups of surgical control and/or ASMT (ASMT-1 and/or ASMT-2). Individual t tests were used to test specific hypothesis about differences between each group of CCD, de-CCD, or de-CCD with ASMT and its corresponding control group for each parameter tested. χ2 Tests were used to identify differences in the incidence of effects. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical results described as significant are based on a criterion of a P value of less than .05.

Results

Repetitive ASMT Suppressed Thermal Hyperalgesia and Mechanical Allodynia After CCD/de-CCD Treatment

The animals with CCD exhibited significant thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia. The foot ipsilateral to CCD became more sensitive to the thermal or mechanical stimulus, but the responses of the foot contralateral to CCD were not significantly changed (data not shown). This results are similar to that we have previously described. [4, 12] After de-CCD (rod withdrawal), CCD-induced painful syndromes, the thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, were significantly, gradually attenuated approximately 40% compared with that in CCD rats and then maintained at this level until 35 and 28 days, respectively. The remained thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia after de-CCD were completely or greatly suppressed (P < .01 vs CCD and de-CCD, P > .05 vs Sham) by repetitive ASMT with protocols in either ASMT-1 with setting 1 or ASMT-2 with setting 2. Both ASMT-1 and ASMT-2, each was applied on the process of L5 and L6 for total 10 manipulations, respectively, produced similar effects on the thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia. Thus, we present only data from the group of ASMT-1 (abbreviated as ASMT, also true in the following figures) in Figure 1. Data from group of ASMT-2 are not shown here.

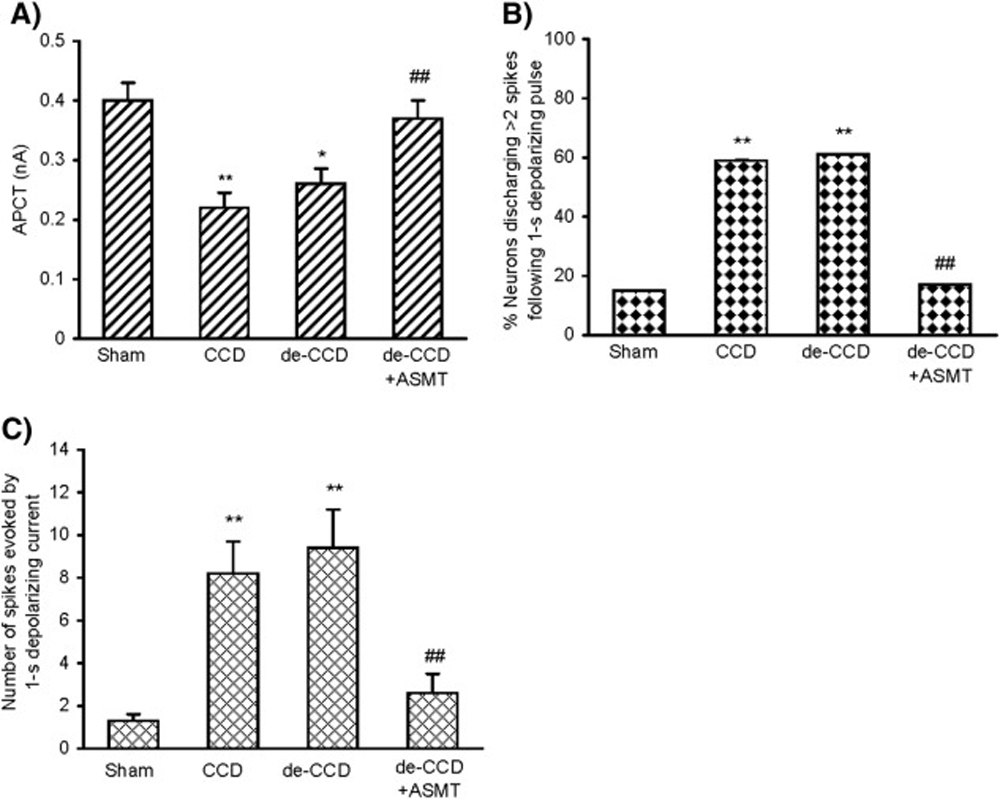

Repetitive ASMT Reduced DRG Neuron Hyperexcitability After CCD/de-CCD

Figure 2 Electrophysiological studies by whole-cell patch clamp recordings showed that the nociceptive small DRG neurons became more excitable after CCD. The APCT decreased significantly in the DRG neurons (P < .01, 1–way ANOVA; Fig 2A ). Hyperexcitability of DRG neurons was also revealed as an enhancement of repetitive discharge evoked by a 50–ms depolarizing current pulse normalized to APCT. There were 13 (59.1%) of 22 CCD DRG neurons responding with 3 or more APs to the normalized depolarizing current, and the rest exhibited 1 or 2 APs, whereas only 15% (3/20) of the neurons from sham control DRG discharged 3 or more APs (P < .01 in each case, χ2 tests; Fig 2B). The mean number of spikes in CCD DRG neurons reached (mean ± SEM) 8.2 ± 1.5 (n = 22) from sham control 1.3 ± 0.3 (n = 20) (P < .01) (Fig 2C). Ten days after the de-CCD, the hyperexcitability of the previously compressed DRG remained at the similar level, that is, de-CCD did not significantly reduce the CCD-induced neural hyperexcitability (P > .05). However, repetitive ASMT resulted in a significant, great decrease of the neural hyperexcitability; the decreased APCT was recovered; and the increased discharges following depolarizing current reduced. Data are summarized in Figure 2

Fig 2 Effects of repetitive ASMT on the DRG neural hyperexcitability after CCD and de-CCD, respectively. (A), Action potential current threshold (minimum current required for evoking an action potential by delivering intracellular currents at 50–ms duration pulse). (B), Number of neurons discharged more than 2 spikes following a 1–second depolarizing current at 2.5 × APCT. (C), Number of repetitive discharges (spikes) evoked by a 1–second depolarizing current. The DRGs from 3 rats in each group were taken on the 28/18/2 days after surgery/de-CCD/ASMT. Number of neurons in each group: Sham = 20, CCD = 22, de-CCD = 18, de-CCD with ASMT = 24. *P < .05, **P < .01 (vs CCD), ##P < .05 (vs CCD and/or de-CCD).

Repetitive ASMT Alleviated CCD/de-CCD DRG Neuron Inflammation

Figure 3 Under a light dissecting microscope, the CCD and CCD/de-CCD DRGs showed clear signs of inflammation, and it appeared to be covered by a layer of connective tissue that was somewhat difficult to remove, and the increased vascularization could be seen on the surface of the ganglia. In contrast, the sham control DRGs looked clear with no obvious blood vessels. These were observed when we prepared the intact DRG preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin staining further showed clear inflammatory signs in the CCD and CCD-de-CCD DRG neurons from rats on the 21 days after CCD surgery and 11 days after de-CCD. The sham control DRG slice is shown in Figure 3A. In the CCD DRG, the neurons were surrounded by significantly increased neuroglia cells. Satellitosis was observed in most of the slices (example given in Fig 3B). Statellitosis is a condition marked by an accumulation of neuroglia cells around the neurons and is often as preclude of the neuronophagia (phagocytosis of nerve cells), which would finally result in cell death. Eleven days after de-CCD, the inflammation signs decreased (Fig 3C). Repetitive ASMT greatly reduced inflammation in de-CCD DRG (Fig 3D). Data are summarized in Figure 3E.

Repetitive ASMT Suppressed Induction of c-Fos and Expression of PKCγ in the Spinal Cord After CCD/de-CCD

Figure 4 Induction of c-Fos protein and expression of PKCγ after inflammation and/or injury have been used as indicators of neural activity and plasticity associated with these states. We used immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining to measure the expression of c-Fos and PKCγ immunoreactivity. Representative photomicrographs and the corresponding counts of Fos-like immunoreactive neurons in the dorsal horn are shown in Figure 4A. As expected, c-Fos expression significantly increased in the dorsal horn in CCD rats. The de-CCD treatment significantly reduced CCD-induced increase in expression of c-Fos. Repetitive ASMT further suppressed expression of c-Fos. Examples are shown in Figure 4A, and data are summarized in Figure 4B.

Figure 5 Alterations of PKCγ immunoreactivity in the dorsal horn associated with CCD, de-CCD, and de-CCD with ASMT are shown in Figure 5. Chronic compression of DRG significantly increased the expression of PKCγ in the superficial layer of the dorsal horn region (laminae I–II). The de-CCD treatment did not significantly reduce the PKCγ expression at the 11 days after de-CCD. Repetitive ASMT significantly suppressed PKCγ expression (Fig 5A). The corresponding measurements of fluorescence intensity are summarized in Figure 5B.

Repetitive ASMT Produced Different Effects on Expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 in Blood Plasma, DRG, and the Spinal Cord

Given that ASMT can attenuate postoperative pain, inhibit the increased nociceptive sensory neuron excitability, reduce DRG inflammation, and suppress the increased expression of induction of c-Fos gene and PKCγ after relief of previous DRG compression, we continued to examine possible alterations of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 in blood plasma and the nerve tissues DRG and spinal cord to understand possible roles of these cytokines in such painful conditions with and without ASMT. These cytokines were measured by ELISA. The results showed that CCD and de-CCD did not produce any detectable change of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 in the plasma. In DRG and the spinal cord, level of IL-1β, but not TNF-α and IL-10, was significantly increased in animals that previously received CCD and then de-CCD.

Figure 6 There was no significant different between groups of CCD and de-CCD. Activator-assisted spinal manipulative therapy in 2 different protocols, ASMT-1 (Activator setting 1) and ASMT-2 (Activator setting 2), significantly reduced the increased level of IL-1β in DRG, but not that in the spinal cord. Activator-assisted spinal manipulative therapy did not affect the unchanged level of TNF-α in both DRG and the spinal cord and the level of IL-10 in DRG. However, both ASMT-1 and ASMT-2 significantly increased the level of IL-10 in the spinal cord. These results indicate that ASMT can reduce the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β in DRG and spinal cord and increase the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord. Data are shown in Figure 6.

Fig 6. Effects of repetitive ASMT on expression of cytokines IL-1b, TNF-a, and IL-10 in plasma, DRG, and the spinal cord after Sham, CCD, de-CCD, and de-CCD with ASMT, respectively. Activator-assisted spinal manipulative therapy was applied with 2 different forces at Activator setting 1 (ASMT-1) and 2 (ASMT-2). Levels of the cytokines in the plasma, DRG, and spinal cord were determined by specific ELISA-based kits. Six rats were included in each of the 5 groups. *P b .05, **P b .01 (vs Sham), # P b .05, ##P b .01 (vs CCD or de-CCD)

Discussion

This research is believed to be the first demonstration that the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord was activated and contributed to spinal manipulation-induced analgesia. The present study demonstrated that spinal manipulation mimicked by repetitive ASMT reduced neuropathic pain induced by primary sensory neuron injury (DRG compression) and the postoperative pain after decompression of the previously compressed sensory neurons; ASMT-induced increased level of the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 in the spinal cord as well as the decreased proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β may contribute to ASMT-induced analgesic effects.

The major findings are 4-fold:(i) repetitive ASMT significantly suppressed the mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia after CCD/de-CCD treatment;

(ii) repetitive ASMT significantly alleviated CCD/de-CCD DRG neuron inflammation;

(iii) repetitive ASMT significantly reduced the increased excitability of the nociceptive DRG neurons after CCD/de-CCD;

(iv) repetitive ASMT inhibited induction of c-Fos gene and expression of PKCγ in the spinal cord after CCD/de-CCD; (v) repetitive ASMT significantly increased the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 in the spinal cord as well as reducing CCD-induced increased proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β in DRG.These findings provide evidence supporting a new mechanism that underlies ASMT-induced analgesia in certain neuropathic and postoperative painful conditions.

Low back pain, in pathogenesis and etiology, may involve neuropathic and inflammatory pain and continues to be a major challenge in clinic. This study provides evidence that repetitive spinal manipulation may be an effective approach for treating certain low back pain due to temporary, reversible sensory neuron injury and/or IVF inflammation. Such analgesic effects may be mediated by spinal manipulation–induced reduction of the nerve tissue inflammation and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β in DRG and the great increase of the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord. This study demonstrates a unique mechanism underlying spinal manipulation–induced relief of chronic pain comparing to the regular analgesics. Spinal manipulation relieves pain through activating the endogenous anti-inflammatory and analgesic systems, but not by suppressing the specific molecular targets that may be responsible for the painful conditions. We know that pathogenesis and etiology of various chronic painful conditions including low back pain are complex and remain elusive, although it is thought that the low back pain may involve in neuropathic and inflammatory mechanisms. Furthermore, mechanisms that underlie the neuropathic and inflammatory pain are also unclear. There is no any single or a couple of specific molecules that could perfectly be responsible for and be the targets for treating low back pain. However, certain techniques and therapies such as spinal manipulation are a good choice, and they are ready for use in clinic to relieve certain chronic painful conditions.

Inflammatory response after inflammation or nerve injury such as DRG compression in this study plays essential roles in behavioral hyperalgesia and hyperexcitability of DRG neurons in inflammatory as well as in neuropathic painful conditions. [7–11, 16–18] Dorsal root ganglion neuron injury and inflammation are the main reasons for low back pain and similar painful conditions in other regions. After injury and/or inflammation to the primary sensory neuron within the DRG, the chemical factors such as cytokines, nerve growth factors, inflammatory mediators, and other substances release and activate and/or change the properties of DRG neurons and spinal dorsal horn neurons as well as increase their excitability and, therefore, contribute to pain and/or hyperalgesia. [4–11, 16] In the present study, CCD treatment produces a chronic compression as well as inflammation on the DRG and the constituents within the IVF (ie, DRG, nerve root, blood and lymph vessels) and may produce ischemia and compromise the delivery of oxygen and nutrients. Our study shows that ASMT can significantly alleviate the symptoms and shorten the duration of mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, DRG inflammation, as well as DRG nociceptive neuron hyperexcitability caused by CCD and the followed postoperative pain (de-CCD treatment).

There are several possibilities of the mechanisms of action for spinal manipulation. For example,(i) the increased movement of the affected intervertebral joints (facets) and the coupled spinal motion may contribute to the effect of spinal manipulation via improving the blood and nutrition supplement to the DRG within the affected IVF; [15]

(ii) Spinal manipulation may “normalize” articular afferent input to the central nervous system with subsequent recovery of muscle tone, joint mobility, and sympathetic activity. [32] It was hypothesized that a chiropractic lumbar thrust could produce sufficient force to coactivate all of the mechanically sensitive receptor types, [33] and SMT made with the Activator is thought to accomplish the same task. [34] Activator SMT may have the capacity to coactivate type III, high-threshold mechanoreceptors. Both type III and IV receptors in diarthrodial joints as well as type II in paravertebral muscles and tendons are responsive to vertebral displacement; [35]

(iii) Spinal manipulation may activate the receptors in the spinal cord and some of the ascending and descending signaling pathways that involve in pain modulation. [36] Studies have shown that certain cytokines and chemokines are involved in normal subjects and patients with neck pain and soft tissue injury, with or without spinal manipulation therapy. [37–40]In the present study, we found that ASMT can activate the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord. This finding provides a new mechanism for understanding the treatment effects of spinal manipulation using ASMT.

The importance of specificity as it relates to the force that is applied to the spinal segment(s) is another important question. Specific SMT with certain forces is important, but it is difficult to determine the “correct” force in practice. Here, we examined applying ASMTs in 2 different forces, ASMT-1 and ASMT-2, representing the SMT force setting at 1 and 2 of the Activator III, respectively, whereas the other parameters in the 2 protocols were kept the same. The results show that ASMT-1 and ASMT-2 result in similar analgesic effect on thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia after CCD/de-CCD (see description in the first paragraph in Results) and on alterations of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 (see Fig 5). Thus, with the experimental protocols in this study, the ASMT with forces at setting 1 and setting 2 of the Activator does not produce significantly different results, suggesting that the force at setting 1 may satisfy the minimal or maximal force requirement, in addition to other parameters, to achieve the treatment effects detected. A further study is needed to systematically examine ASMT with a larger range of force settings to determine the specificity of force use in spinal manipulation.

Future Studies

Further studies are needed to identify possible roles of the newly identified molecular targets such as ephrinB-EphB receptor [41–44] and WNT signaling [45, 46] that are important in production and maintenance of neuropathic and cancer pain in spinal manipulation–induced analgesia. In addition, a series of quantitative studies on the Activator settings including forces, frequencies, and others need to be conducted in more details. Furthermore, it is time to conduct clinical translational studies in patients; thus, the scientific findings in this current and our previous studies [4, 13, 15] focusing on the spinal manipulation and low back pain may be translated to improving clinical care of the patients with similar painful conditions.

Limitations

The limitations for this study may include at least 2–fold:(i) The force settings reading in the AAI are obviously not the actual forces applied to the spinal processes in the experimental animals. The actual forces applied to the spinal processes using AAI should be measured.

(ii) The results showed that ASMT significantly increased level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord and reduced level of proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β in DRG.It was not identified which of these 2 alterations is more important or both are equally important to the ASMT-induced analgesia.

Conclusion

Our results showed that repetitive ASMT significantly suppressed neuropathic pain after CCD and the postoperative pain after de-CCD, reduced the increased excitability of CCD and de-CCD DRG neurons, attenuated the DRG inflammation, and inhibited induction of c-Fos and expression of PKC in the spinal dorsal horn. Most interestingly, ASMT significantly increased level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the spinal cord and reduced level of IL-1β in DRG in CCD and de-CCD rats. These results suggest that ASMT may attenuate neuropathic pain through, at least partly, activating the endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10.

Funding Sources and Potential Conflicts of Interest

This work was supported by grants from Australia Spinal Research Foundation (LG2011-5) and National Institutes of Health (NIH-1R43AT004933-01). No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): X.J.S., A.W.F., A.L.R.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): X.J.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): X.J.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): Z.J.H., W.B.S., X.S.S.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): Z.J.H., X.J.S., H.N., R.L.R.

Literature search (performed the literature search): X.J.S., A.L.R.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): X.J.S.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): X.J.S.

References

Devor M

The pathophysiology of damaged peripheral nerves.

in: Wall PD Melzack R Text Book of Pain. 3rd ed.

Churchill Livingstone, London1994: 79-100Brisby H Olmarker K Larsson K Nutu M Rydevik B

Proinflammatory cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid and serum

in patients with disc herniation and sciatica.

Eur Spine J. 2002; 11: 62-66Song XJ Zhang JM Hu SJ LaMotte RH

Somata of nerve-injured neurons exhibit enhanced responses

to inflammatory mediators.

Pain. 2003; 104: 701-709Song XJ Xu DS Vizcarra C Rupert RL

Onset and recovery of hyperalgesia and hyperexcitability of sensory

neurons following intervertebral foramen volume reduction and restoration.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003; 26: 426-436Neumann S Doubell TP Leslie T Woolf CJ

Inflammatory pain hypersensitivity mediated by

phenotypic switch in myelinated primary sensory neurons.

Nature. 1996; 384: 360-364Cui JG Holmin S Mathiesen T Meyerson BA Linderoth B

Possible role of inflammatory mediators in tactile

hypersensitivity in rat models of mononeuropathy.

Pain. 2000; 88: 239-248Wagner R Myers RR

Endoneurial injection of TNF-alpha produces neuropathic pain behaviors.

Neuroreport. 1996; 7: 103-111Waxman SG Kocsis JD Black JA

Type III sodium channel mRNA is expressed in embryonic but not adult

spinal sensory neurons, and is reexpressed following axotomy.

J Neurophysiol. 1994; 72: 466-470Song XJ Hu SJ Greenquist K LaMotte RH

Mechanical and thermal cutaneous hyperalgesia and ectopic neuronal

discharge in rats with chronically compressed dorsal root ganglia.

J Neurophysiol. 1999; 82: 3347-3358Song XJ Vizcarra C Xu DS Rupert RL Wong ZN

Hyperalgesia and neural excitability following injuries to the peripheral

and central branches of axon and somata of dorsal root ganglion neurons.

J Neurophysiol. 2003; 89: 2185-2193Song XJ Wang ZB Gan Q Walters ET

cAMP and cGMP pathways contribute to expression of hyperalgesia and

sensory neuron hyperexcitability following dorsal root

ganglion compression in the rat.

J Neurophysiol. 2006; 95: 479-492Song XJ Hu SJ Greenquist KW Zhang JM LaMotte RH

Mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia and ectopic neuronal

discharge after chronic compression of dorsal root ganglia.

J Neurophysiol. 1999; 82: 3347-3358Song XJ Gan Q Wang ZB Rupert RL

Hyperalgesia and hyperexcitability of sensory neurons induced by local

application of inflammatory mediators: an animal model of

acute lumbar intervertebral foramen inflammation.

Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2004; 30Song XJ Gan Q Wang ZB Rupert RL

Lumbar intervertebral foramen inflammation-induced hyperalgesia

and hyperexcitability of sensory neurons in the rat.

FASEB J. 2004; 1616Song XJ Gan Q Cao JL Wang ZB Rupert RL

Spinal manipulation reduces pain and hyperalgesia after

lumbar intervertebral foramen inflammation in the rat.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006; 29: 5-13Kizhakkeveettil A, Rose K, Kadar GE

Integrative Therapies for Low Back Pain That Include Complementary

and Alternative Medicine Care: A Systematic Review

Glob Adv Health Med. 2014 (Sep); 3 (5): 49–64Peterson CK Humphreys BK Vollenweider R Kressig M Nussbaumer R

Outcomes for chronic neck and low back pain patients after

manipulation under anesthesia: a prospective cohort study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014; 37: 377-382Kolberg C Horst A Moraes MS et al.

Peripheral oxidative stress blood markers in patients with chronic

back or neck pain treated with high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015; 38: 119-129Bronfort G Haas M Evans R

The clinical effectiveness of spinal manipulation for musculoskeletal conditions.

in: Haldeman S Principle and Practice of Chiropractic. 3rd ed.

McGraw Hill, New York 2005: 147-165Vernon H

The treatment of headache, neurologic, and non-musculoskeletal disorders by spinal manipulation.

in: Haldeman S Principle and Practice of Chiropractic. 3rd ed.

McGraw Hill, New York 2005: 167-182Fuhr AW Menke JM

Activator methods chiropractic technique.

Top Clin Chiropr. 2002; 9: 30-43Richard DR

The activator story: development of a new concept in chiropractic.

Chiropr J Austr. 1994; 24: 28-32Osterbauer P Fuhr AW Keller TS

Description and analysis of activator methods

chiropractic technique, advances in chiropractic.

. 1995; 2: 471-520Fuhr AW Smith DB

Accuracy of piezoelectric accelerometers measuring

displacement of a spinal adjusting instrument.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1986; 9: 15-21Smith DB Fuhr AW Davis BP

Skin accelerometer displacement and relative bone movement of adjacent

vertebrae in response to chiropractic percussion thrusts.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989; 12: 26-37Song XJ Zheng JH Cao JL Liu WT Song XS Huang ZJ

EphrinB-EphB receptor signaling contributes to neuropathic pain by

regulating neural excitability and spinal synaptic plasticity in rats.

Pain. 2008; 139: 168-180Wang ZB Gan Q Rupert RL Zeng YM Song XJ

Thiamine, pyridoxine, cyanocobalamin and their combination inhibit

thermal, but not mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with

primary sensory neuron injury.

Pain. 2005; 114: 266-277Song XS Huang ZJ Song XJ

Thiamine suppresses thermal hyperalgesia, inhibits hyperexcitability,

and lessens alterations of sodium currents in injured,

dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats.

Anesthesiology. 2009; 110: 387-400Zheng JH Walters ET Song XJ

Dissociation of dorsal root ganglion neurons induces hyperexcitability

that is maintained by increased responsiveness to cAMP and cGMP.

J Neurophysiol. 2007; 97: 15-25Huang ZJ Li HC Cowan AA Liu S Zhang YK Song XJ

Chronic compression or acute dissociation of dorsal root ganglion

induces cAMP-dependent neuronal hyperexcitability through activation of PAR2.

Pain. 2012; 153: 1426-1437Huang ZJ Li HC Liu S Song XJ

Activation of cGMP-PKG signaling pathway contributes to neuronal hyperexcitability

and hyperalgesia after in vivo prolonged compression or in vitro

acute dissociation of dorsal root ganglion in rats.

Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2012; 64: 563-576Henderson CNR

Three neurophysiological theories on the chiropractic subluxation.

in: Gatterman MI Foundation of Chiropractic Subluxation,

St. Louis, Mosby 1995Keller TS

In vivo transient vibration assessment of the normal human thoracolumbar spine.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000; 23: 521-530Gillette RG

A speculative argument for the coactivation of diverse

somatic receptor populations by forceful chiropractic adjustments.

Man Med. 1987; 3: 1-14Nathan M Keller TS

Measurement and analysis of the in vivo posteroanterior impulse

response of the human thoracolumbar spine: a feasibility study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994; 17: 431-441Brodeur R

The audible release associated with joint manipulation.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995; 18: 155-164Cao TV Hicks MR Campbell D Standley PR

Dosed myofascial release in three-dimensional bioengineered tendons:

effects on human fibroblast hyperplasia, hypertrophy, and cytokine secretion.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36: 513-521Eagan TS Meltzer KR Standley PR

Importance of strain direction in regulating human fibroblast proliferation

and cytokine secretion: a useful in vitro model for soft

tissue injury and manual medicine treatments.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007; 30: 584-592Teodorczyk-Injeyan JA Injeyan HS Ruegg R

Spinal manipulative therapy reduces inflammatory cytokines

but not substance P production in normal subjects.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006; 29: 14-21Teodorczyk-Injeyan JA Triano JJ McGregor M Woodhouse L Injeyan HS

Elevated production of inflammatory mediators including nociceptive

chemokines in patients with neck pain: a cross-sectional evaluation.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011; 34: 498-505Liu S Liu YP Song WB Song XJ

EphrinB-EphB receptor signaling contributes to bone cancer pain via

Toll-like receptor and proinflammatory cytokines in rat spinal cord.

Pain. 2013; 154: 2823-2835Liu S Liu WT Liu YP Dong HL Henkemeyer M Song XJ

Blocking EphB1 receptor forward signaling in spinal cord relieves

bone cancer pain and rescues analgesic effect of morphine treatment in rodents.

Cancer Res. 2011; 71: 4392-4402Song XJ Cao JL Li HC Song XS Xiong LZ

Upregulation and redistribution of ephrin1B-EphB1 receptor signaling

in dorsal root ganglion and spinal dorsal horn after

nerve injury and dorsal rhizotomy.

Eur J Pain. 2008; 12: 1031-1039Han Y Song XS Liu WT Henkemeyer M Song XJ

Targeted mutation of EphB1 receptor prevents development of neuropathic

hyperalgesia and physical dependence on morphine in mice.

Mol Pain. 2008; 4: 60Zhang YK Huang ZJ Liu S Liu YP Song AA Song XJ

WNT signaling underlies the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in rodents.

J Clin Invest. 2013; 123: 2268-2286Liu S Liu YP Huang ZJ et al.

Wnt/Ryk signaling contributes to neuropathic pain by regulating sensory

neuron excitability and spinal synaptic plasticity in rats.

Pain. 2015; 156: 2572-2584

Return to CHIROPRACTIC ADJUSTING

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 2-22-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |