Otitis Media and Spinal Manipulative Therapy:

A Literature ReviewThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Chiropractic Medicine 2012 (Sep); 11 (3): 160169 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Katherine A. Pohlman, Monisa S. Holton-Brown

Clinical Project Manager II,

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Palmer College of Chiropractic,

Davenport, IA.OBJECTIVE: Otitis media (OM) is one of the common conditions for doctor visits in the pediatric population. Spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) may be a potential conservative treatment of OM. The purpose of this study is to review the literature for OM in children, outlining the diagnosis of OM, SMT description, and adverse event notation.

METHODS: Databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, Index to Chiropractic Literature, The Allied and Complementary Medicine, and Alt Health Watch) were queried and hand searches were performed to identify relevant articles. All potential studies were independently screened for inclusion by both authors. The inclusion criteria were as follows: written in the English language, addressed OM, involved human participants 6 years or younger, and addressed SMT. Studies were evaluated for overall quality using standardized checklists performed independently by both authors.

RESULTS: Forty-nine articles were reviewed: 17 commentaries, 15 case reports, 5 case series, 8 reviews, and 4 clinical trials. Magnitude of effect was lower in higher-quality articles. No serious adverse events were found; minor transient adverse effects were noted in 1 case series article and 2 of the clinical trials.

CONCLUSIONS: From the studies found in this report, there was limited quality evidence for the use of SMT for children with OM. There are currently no evidence to support or refute using SMT for OM and no evidence to suggest that SMT produces serious adverse effects for children with OM. It is possible that some children with OM may benefit from SMT or SMT combined with other therapies. More rigorous studies are needed to provide evidence and a clearer picture for both practitioner and patients.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

Otitis media (OM) is one of the primary conditions for which antibiotics are prescribed in the United States. [1] Failure to distinguish acute otitis media (AOM) from otitis media with effusion (OME) is a possible reason for the use of antibiotics when they are not indicated, and this may contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant organisms. Acute OM and OME both are upper respiratory tract infections, but children with AOM also have pain and fever. The current recommendation for [2]the treatment of AOM is to use an antibacterial agent (usually amoxicillin). [3] Antimicrobial therapy is not recommended for patients with OME because it typically resolves spontaneously. [2] Because of the concerns of increasing antibiotic-resistant infections and overuse of antibiotics, other methods for conservative care for the common condition of OME are needed. Methods traditionally associated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) are usually conservative and do not include pharmaceutical drugs or surgery. Currently, CAM is not considered a potential treatment of either AOM or OME because of limited evidence in the literature. [3, 4]

In addition to musculoskeletal disorders, both the chiropractic and osteopathic professions have claimed that spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) may alleviate disorders involving visceral organs, such as OME. [5, 6] Hypotheses regarding how SMT accomplishes this generally attribute the effects of SMT to biomechanical changes produced in the spine, which subsequently mediate changes in sympathetic or parasympathetic nerve activity. [5, 6]

Certain chiropractic and osteopathic manipulative techniques address the function of cranial structures (including intraoral structures) for treatment of OM. [7] These structures may directly affect the Eustachian tube (ET), which is thought to be the primary structure involved in reoccurrence of OM. [8] The ET has an increase in goblet cells during and up to at least 6 months after OM regardless of the bacterium causing the condition. Otitis media causes an increased secretory capacity of the ET. This increase may contribute to the excessive mucus and deteriorated ET function. These factors could also predispose the patient to the reoccurrence of OM or to a more aggressive middle ear complication.

Another hypothesis, which also indirectly involves the ET, is the impact of cervical manipulation on the lymphatic and muscular systems. Lymphatic flow requires muscular contractions, arterial pulsations, and external compression of body tissues. It is hypothesized that restricted joint movement within the cervical spine may result in muscle hypertonicity restricting lymphatic drainage away from the cranial region. This hypothesis suggests that cervical SMT reduces tension within hypertonic muscles, thus increasing lymphatic drainage. [9]

At present, there has not been a review of the literature summarizing the effects of spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) on OM or the safety of SMT for treating OM. The purpose of this study was to review the literature on the treatment effects of SMT and/or mobilization (including both chiropractic and osteopathic approaches) for all types of OM. This study also evaluates the literature for information relating to the diagnosis of OM, SMT description, and reported adverse events.

Methods

Sources of information

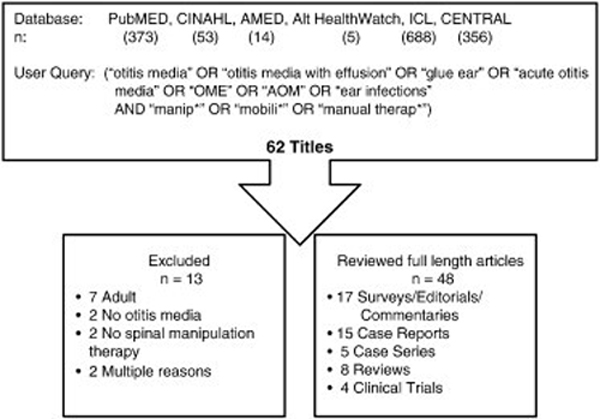

Figure 1 Relevant studies were identified using the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Index to Chiropractic Literature (ICL), The Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED), and Alt Health Watch. All databases were searched from inception thru March 2011 (See Figure 1). We checked reference lists of relevant studies to identify cited articles not captured by electronic searches.

Selection criteria

Because there are few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and other higher levels of evidence for CAM therapies, such as SMT, we included all levels of evidence. Allowing all levels of evidence provides a comprehensive review of the current state of literature on this subject.

Articles were included if they met the following criteria:(1) written in the English language,

(2) addressed OM (acute or chronic),

(3) involved human participants 6 years or younger,

(4) addressed SMT or osteopathic manipulative therapy to a spinal segment or cranial bone.

Search terms and delimiting

Search terms for all databases (except 1) included otitis media OR otitis media with effusion OR glue ear OR acute otitis media OR OME OR AOM OR ear infections AND manip* OR mobili* OR manual therap*. The ICL database was only searched using otitis media OR otitis media with effusion OR glue ear OR acute otitis media OR OME OR AOM OR ear infections. All were searched for references written in English and involved human participants.

All titles and abstracts of potential relevant studies were then independently screened for inclusion by both authors. Any disagreements about inclusion were discussed until consensus was reached.

Quality assessment

Studies included in the review underwent a quality assessment performed independently by both assessors, with consensus reached between them. If consensus could not be reached, another reviewer would have been invited to resolve consensus. We used the checklist developed by the Canadian Medical Association Journal to assess the quality of case reports [10]; Yang et al developed the checklist for case series [11]; CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) was used for the clinical trials [12]; and QUORUM (Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses) was used to evaluate the review articles. [13] From the results of each checklist, if 25% or less of the criteria were addressed, the article was scored as poor; if 26% to 50% of the criteria were addressed, the article was scored as fair; if 51% to 75% of criteria were addressed, the article was scored as good; and if 76% to 100% of the criteria were addressed, the article was scored as excellent.

Results

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5 We identified 1,489 articles and found 62 to be potentially eligible (see Figure 1). Of the 62 reports 17 were surveys/editorials/commentaries, 15 were case reports, 5 were case series, 8 were reviews, and 4 were clinical trials. There were a total of 13 reports that could not be included after reviewing the entire article: 7 had patients older than 6 years, 2 did not include OM, 2 did not have SMT as part of the interventions, and 2 had multiple reasons. Thus, 49 articles were included in the final evaluation.

There were 15 case reports (Table 1) included in this study. Each resulted in a decrease of OM symptoms or improved hearing. Thirteen of the articles involved chiropractic SMT, 1 used osteopathic care, and 1 described integrative care including chiropractic. The type of OM was described as definitely chronic in 9 of the articles and definitely acute in 3. Overall, the quality of the articles was fair; and there was no mention of adverse events.

Case series, described in Table 2, also demonstrated decreased recurrent symptoms or number of reoccurring episodes of OM. There were 4 articles that used chiropractic care and 1 that used osteopathic manipulative care. The exact definition of OM was different for each article. One article reported that there were no complications following care. In general, the quality of these articles was rated as good.

There were a total of 4 articles describing 3 different clinical trials (Table 3). One of the trials recruited acute OM patients (2 articles), 1 had chronic OM with effusion, and the final article recruited patients with recurrent OM. There were a total of 167 patients enrolled into these clinical trials, and most reported a decrease in symptoms. Two of the 3 clinical trials used osteopathic manipulation. Overall, the quality of the articles was excellent, with 2 of the articles reporting minor, transient adverse events.

The review articles' quality ranged from excellent (2) to good (2) to fair (3) (Table 4). All of the review articles were published in peer-reviewed journals during the past 10 years. The overarching summary statements of these articles varied greatly. One stated that SMT may decrease frequency of OM, another stated that the results are inconclusive, and another found no credible solid evidence.

The final table (Table 5) reports the list of commentaries (10), letters to editors (3), cross-sectional surveys (3), and protocols (1) on the subject of OM and SMT. Conclusions varied with the type of writing, but the majority supported the use of SMT for OM.

Discussion

Most of the literature from this narrative review comes from case reports, case series, surveys, and commentaries rather than RCTs of high quality. There appears to be a potential benefit from SMT in pediatric patients with OM; but more rigor needs to occur with quality of writing, reporting of adverse events, and reporting diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

For this review, the higher the literature was on the evidence pyramid, the better its quality. There are many books, commentaries, and checklists to help authors ensure that their manuscript adds value to the literature. [62] However, writing is a difficult and time-consuming task. The quality of OM manuscripts could be improved tremendously if clarity regarding the mechanisms of SMT, how the diagnosis was reached, and reports of adverse events were included.

Few if any adverse events have been reported with SMT for the pediatric population. [63] Causation and incident rates have not been studied; so careful reporting of events, even minor, needs to be included when writing a manuscript. All checklists and other tools for writing manuscripts should include this item to ensure that authors are aware of its importance. When reported amongst the articles in this review, adverse effects were minor and transient.

Pichichero [64] has been writing about the importance of diagnostic accuracy of OM and its difficulties for several years. Ferrance and Miller [39] describe the 3 separate and distinct entities of OM and how they are typically differentiated by otoscopy with insufflation to check for appropriate movement of the tympanic membrane. This procedure requires rigorous training, and its difficulty is well known.

Clinical trials are most often designed to be explanatory or efficacy trials to determine whether an intervention has an effect under ideal circumstances. [65] Case reports classically occur in real-world clinical settings. The next step involves conducting effectiveness or pragmatic trials, which are intended to measure the degree of beneficial effect in a more real-world setting. A pragmatic clinical trial that explores the benefits of SMT in children with OM enhances its generalizability for clinical practitioners. [66] If these trials provide strong evidence for an intervention, establishing protocols for efficacy trials can be substantiated with the prior pragmatic trials' intervention and clinical settings.

Limitations

This literature review has the inherent limitation of misleading conclusions. The use of more reviewers or a formalized analysis could have reduced potential bias and misleading conclusions. A second limitation of this review is the use of checklists. Checklists remove considerable subjectivity, but reviewer interpretation and limited criterion can lead to misjudgment or improper scoring of an article. Another limitation was that this was not a rigorous systematic review. We attempted to retrieve all relevant articles; but without using all the methods of a systematic review, we may have inadvertently missed some articles. The studies included in this literature review may not have included or accurately reported adverse events; thus, it is possible that adverse events were underreported.

Conclusions

From the 49 studies (17 surveys/editorials/commentaries, 15 case reports, 5 case series, 8 reviews, and 4 clinical trials) found in this report, there was limited quality evidence for the use of SMT for children with OM. There are currently no evidence to support or refute using SMT for OM and no evidence to suggest that SMT produces serious adverse effects for children with OM. More rigorous studies are needed to provide evidence and a clearer picture for both practitioner and patients.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Maria A Hondras, DC, MPH; and Cynthia R Long, PhD; and Angela Ballew, DC, MS, for assistance with this manuscript. They also thank Dana Lawrence, Paige Morgenthal, and John Stites for their editorial assistance.

REFERENCES:

McCaig L.F., Besser R.E., Hughes J.M.

Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents.

JAMA. 2002;287:30963102

Dowell SF, Schwartz B, Phillips WR.

Appropriate use of antibiotics for URIs in children: part I. Otitis media and acute sinusitis. The Pediatric URI Consensus Team.

Am Fam Physician 1998;58:1113-8, 1123

Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media.

Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media.

Pediatrics. 2004;113:14511465

American Academy of Pediatrics.

Otitis media with effusion.

Pediatrics. 2004;113:14121429

Leach R.A.

The chiropractic theories.

3rd ed. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1994

Dhami M.S.I., DeBoer K.F.

Systemic effects of spinal lesions.

In: Haldeman S., editor. Principles and practice of chiropractic.

2nd ed. Appleton & Lange; Connecticut: 1992. pp. 115136.

Pratt-Harrington D.

Galbreath technique: a manipulative treatment for otitis media revisited.

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100:635639

Caye-Thomasen P., Tos M.

Eustachian tube gland tissue changes are related to bacterial species in acute otitis media.

Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:101110

Fysh P.N. 1st ed.

International Chiropractos Associatiotion Council on Chiropractic Pediatrics;

Arlington, VA: 2002. Chiropractic care for the pediatric patient.

Squires B.P.

Case reports: what editors want from authors and peer reviewers.

CMAJ. 1989;141:379380

Yang A.W., Li C.G., Da C.C., Allan G., Reece J., Xue C.C.

Assessing quality of case series studies: development and validation of an instrument by herbal medicine CAM researchers.

J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:513522

Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D.

CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials.

BMJ. 2010;340:c332

Moher D., Cook D.J., Eastwood S., Olkin I., Rennie D., Stroup D.F.

Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses.

Lancet. 1999;354:18961900

McCoy P., Boutilier A., Black P.

Resolution of Otitis Media in a Nine Month Old Undergoing Chiropractic Care:

A Case Study and Selective Review of the Literature

J Pediatr Matern Fam Health. 2010:99106Cuthbert S.C., Rosner A.L.

Applied kinesiology management of candidiasis and chronic ear infections: a case history.

J Pediatr Mater Fam Health. 2010:122129

Brown C.

Improved hearing and resolution of otitis media with effusion following chiropractic care to reduce vertebral subluxation.

J Pediatr Matern Fam Health. 2009:17

Erickson K., Shalts E., Kligler B.

Case study in integrative medicine: Jared C, a child with recurrent otitis media and upper respiratory illness.

Explore (NY) 2006;2:235237

Alcantara J., Beattie M.

The successful chiropractic care of a patient with spinal subluxations and chronic bilateral glue ear

J Chiropr Educ. 2004;18:36

Saunders L.

Chiropractic Treatment of Otitis Media with Effusion: A Case Report

Clinical Chiropractic 2004 (Dec); 7 (4): 168173Stenson J.

The child's book of alternatives.

Health. 2004:121176

Hochman J.

The management of acute otitis media using S.O.T. and S.O.T. craniopathy.

Todays Chiropr. 2001:4143

Khorsid K.

Case reportVicky.

ICA Rev. 2001;57:6263

Hough D.W.

Chiropractic care for otitis media patients.

Todays Chiropr. 1999:5457

Warner S.P., Warner T.M.

Case report: autism and chronic otitis media.

Todays Chiropr. 2012:8285

Amalu W.

Cortical blindness, cerebral palsy, epilepsy and recurring otitis media: a case study in chiropractic management.

Todays Chiropr. 1998:1624

Thomas D.

Irritable child with chronic ear effucsion/infections responds to chiropractic care.

Chiropr Pediatr. 1997;3:1314

Phillips N.J.

Vertebral Subluxation and Otitis Media: A Case Study

Chiropractic: The J of Chiro Res and Clin Inves 1992; 8 (2): 3840Degenhardt B.F., Kuchera M.L.

Osteopathic evaluation and manipulative treatment in reducing the morbidity of otitis media: a pilot study.

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106:327334

Zhang J.Q., Snyder B.J.

Effect of the toftness chiropractic adjustments for children with acute otitis media.

J Vertebral Subluxation Res. 2004:14

Fallon J.M.

The Role of the Chiropractic Adjustment in the Care and Treatment of 332 Children with Otitis Media

Journal of Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 1997 (Oct); 2 (2): 167183Fysh P.

Chronic recurrent otitis media: case series of five patients with recommendations for case management.

J Clin Chiropr Pediatr. 1996;1:6678

Froehle R.M.

Ear Infection: A Retrospective Study Examining Improvement From Chiropractic Care and Analyzing Influencing Factors

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1996 (Mar); 19 (3): 169177Wahl R.A., Aldous M.B., Worden K.A., Grant K.L.

Echinacea purpurea and osteopathic manipulative treatment in children with recurrent otitis media: a randomized controlled trial.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:56

Zaphiris A., Mills M.V., Jewell N.P., Boyce W.T.

Osteopathic manipulative therapy and otitis media: does improving somatic dysfunction improve clinical outcomes?

JAOA. 2004;104:11

Mills M.V., Henley C.E., Barnes L.L., Carreiro J.E., Degenhardt B.F.

The use of osteopathic manipulative treatment as adjuvant therapy in children with recurrent acute otitis media.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:861866

Sawyer C.E., Evans R.L., Boline P.D., Branson R., Spicer A.

A Feasibility Study of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation Versus Sham Spinal Manipulation for

Chronic Otitis Media with Effusion in Children

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999 (Jun); 22 (5): 292298Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leiniger B, Triano J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: The UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Feb 25); 18 (1): 3Cole S., Reed J.

When to consider osteopathic manipulation.

J Fam Pract. 2010;59:E2

Ferrance R.J., Miller J.

Chiropractic diagnosis and management of non-musculoskeletal conditions in children and adolescents.

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010;18:14

Alcantara J.

The chiropractic care of children with otitis media: a systematic review of the literature utilizing whole systems research evaluation and meta-synthesis.

J Chiropr Educ. 2009;23:59

Leighton J.M.

Does manual therapy such as chiropractic offer an effective treatment modality for chronic otitis media?

Clin Chiropr. 2009;12:144148

Hawk C, Knorsa R, Lisi A, Ferrance RJ, Evans MW.

Chiropractic Care for Nonmusculoskeletal Conditions: A Systematic Review

With Implications For Whole Systems Research

J Altern Complement Med. 2007 (Jun); 13 (5): 491512Carr R.R., Nahata M.C.

Complementary and alternative medicine for upper-respiratory-tract infection in children.

Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:3339

Ernst E.

Chiropractic manipulation for non-spinal paina systematic review.

N Z Med J. 2003;116:U539

Steele K.M., Viola J., Burns E., Carreiro J.E.

Brief report of a clinical trial on the duration of middle ear effusion in young children using a standardized osteopathic manipulative medicine protocol.

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110:278284

Alcantara J., Ohm J., Kunz D.

The Chiropractic Care of Children

J Altern Complement Med. 2010 (Jun); 16 (6): 621626Pohlman, KA, Hondras, MA, Long, CR, and Haan, AG.

Practice Patterns of Doctors of Chiropractic With a Pediatric Diplomate:

A Cross-sectional Survey

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010 (Jun 14); 10: 26Hewitt E.G.

Using integrative medicine.

Altern Complement Ther. 2012;14:248

Galgano R.

Hope for larger study on otitis media.

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107:277278

Orenstein R.

Study on recurrent otitis media: potential value vs actual value of OMT.

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107:278279

Fallon J.

Pediatric otitis media.

DC Tracts. 2004:4

Killinger L.Z.

Abstracts and commentaries: chiropractic and pediatrics.

DC Tracts. 2004;16:910

Pichichero M.E.

Osteopathic manipulation to prevent otitis mediadoes it work?

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:852853

Chiropractic approach to the ear.

J Am Chiropr Assoc. 2002:1219

Warner S.

Pediatric power:childhood ear infections.

Chiropr J. 2000;15:20

Lamm L., Ginter L.

Otitis media: a conservative chiropractic management protocol.

Top Clin Chiropr. 1998;5:1828

Bowers L.J.

Clinical assessment of selected periatric conditions: guidelines for the chiropractic physician.

Top Clin Chiropr. 1997;4:18

DiGiorgi D.

Chiropractic management of otitis media in children.

J Am Chiropr Assoc. 1997:4348

Vallone S., Fallon J.M.

Treatment protocols for the chiropractic care of common pediatric conditions: otitis media and asthma.

J Clin Chiropr Pediatr. 1997;2:113115

Whiteside M.

Glue ear.

Heres Health. 1993:6869

Hendricks C.L., Larkin-Thier S.M.

Otitis media in young children.

Chiropractic. 1989;2:913

Peat J., Elliot E., Baur L., Keena V.

Scientific writing: easy when you know how.

BMJ Books; Tavistock Square, London: 2002

Vohra, S, Johnston, BC, Cramer, K, and Humphreys, K.

Adverse Events Associated with Pediatric Spinal Manipulation: A Systematic Review

Pediatrics. 2007 (Jan); 119 (1): e275e283Pichichero M.E.

Acute otitis media: part I. Improving diagnostic accuracy.

Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:20512056

Godwin M., Ruhland L., Casson I., MacDonald S., Delva D., Birtwhistle R.

Pragmatic controlled clinical trials in primary care: the struggle between external and internal validity.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:28

Gartlehner G., Hansen R.A., Nissman D., Lohr K.N., Carey T.S.

AHRQ Publication No. 06-0046. 2006.

Criteria for distinguishing effectiveness from efficacy trials in systematic reviews.

Return to OTITIS MEDIA

Since 3202013

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |