Diagnosis and Treatment of Sciatica This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: British Medical Journal 2019 (Nov 19); 367: l6273 ~ FULL TEXT

Rikke K Jensen, Alice Kongsted, Per Kjaer, Bart Koes

Center for Muscle and Joint Health,

Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics,

University of Southern Denmark,

Odense, Denmark.

What you need to know

Sciatica is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms of radiating pain in one leg with or without associated neurological deficits on examination

Most patients improve over time with conservative treatment including exercise, manual therapy, and pain management

Imaging is not required to confirm the diagnosis and is only requested if pain persists for more than 12 weeks or the patient develops progressive neurological deficits

Urgently refer patients with signs of urinary retention or decreased anal sphincter tone, which suggest cauda equina syndrome

Surgery is an option if symptoms do not improve after 6-8 weeks of conservative treatment. It may speed up recovery but the effect is similar to conservative care at one year

Sciatica is commonly used to describe radiating leg pain. It is caused by inflammation or compression of the lumbosacral nerve roots (L4–S1) forming the sciatic nerve. [1] Sciatica can cause severe discomfort and functional limitation.

Recently updated clinical guidelines in Denmark, the US, and the UK highlight the role of conservative treatment for sciatica. [2–4] In this Clinical Update, we provide an overview for non-specialists on diagnosing sciatica and key principles in its management.

The term “sciatica” is not clearly defined and it is often used inconsistently by clinicians and patients. [5] Radicular pain and lumbosacral radicular syndrome have been suggested as alternatives. [6] In this article, we use sciatica and radicular pain synonymously. Radiculopathy describes involvement of the nerve root, which causes neurological deficit including weakness or numbness.

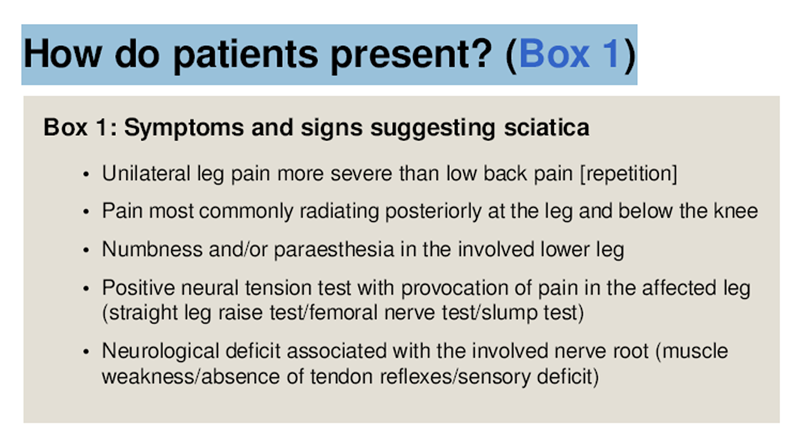

How do patients present? (Box 1)

Box 1 People with sciatica usually describe aching and a sharp leg pain radiating below the knee and into the foot and toes. [7] The pain can have a sudden or slow onset and varies in severity. Most people report coexisting low back pain. Disc herniations affecting the L5 or S1 nerve root are more common and cause pain at the back or side of the leg and into the foot and toes. [8] If L4 root is affected, pain is localised to the front and lateral side of the thigh. [7] Tingling or numbness and loss of muscle strength in the same leg are other symptoms that suggest nerve root involvement.

How common is sciatica?

The prevalence of sciatica varies between studies. In a primary care study in the UK (609 patients) about 60% of patients with back and leg pain were clinically diagnosed with sciatica. [9] In a Danish primary care study in patients with low back pain, 2% of patients in chiropractic clinics (947 patients) and 11% in general practices (324 patients) had associated neurological findings confirming sciatica. [10]

What are the causes?

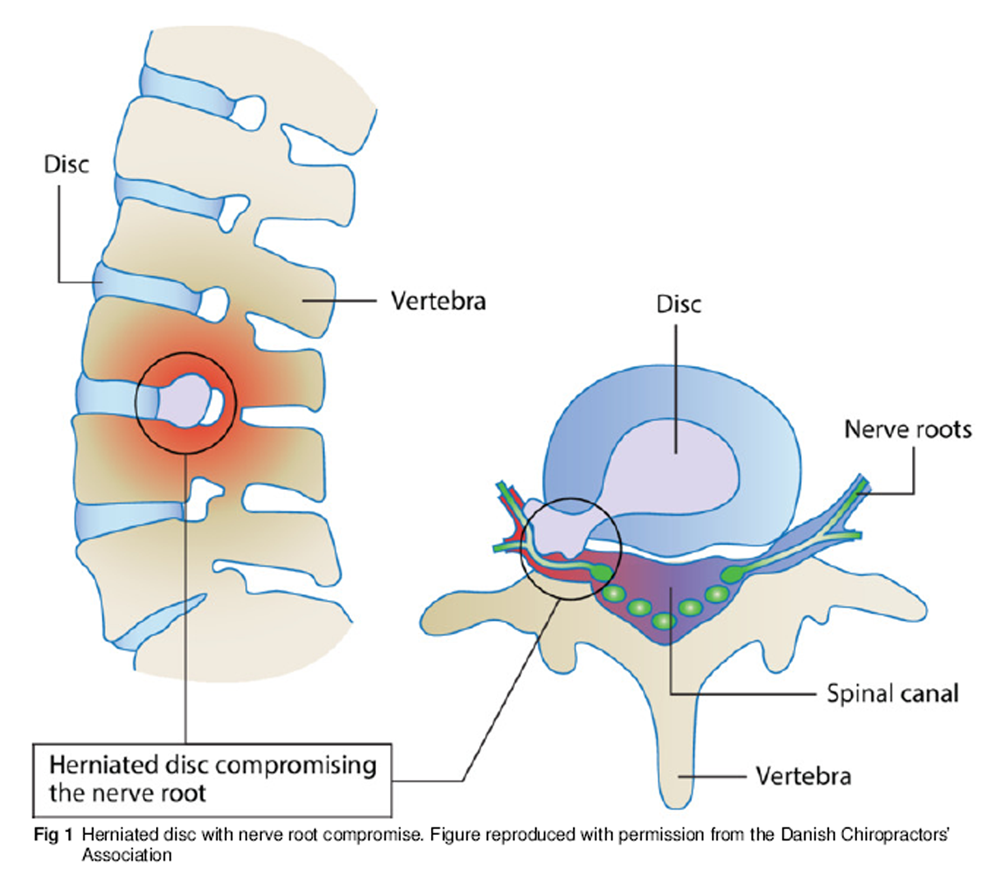

Figure 1 Compression of the nerve root and resultant inflammation play a role in pathogenesis of sciatica. [1] Disc herniation resulting from age related degenerative changes, and rarely trauma, is the commonest cause [1, 9] (Figure 1). The inflammatory response induces resorption of the herniated disc material, and is thought to be the reason why most people improve without surgery. Foraminal stenosis and, less commonly, soft tissue stenosis caused by cysts, tumours, or extraspinal pathology are other causes. [11] Rarely, extraspinal pathology in the lumbosacral nervous plexus such as neoplasm, trauma, infection, or gynaecological conditions, or muscle entrapment such as piriformis syndrome can mimic symptoms of disc herniation. [11] Smoking, obesity, and manual labour are modifiable risk factors for the first episode of sciatica as per a recent systematic review (eight studies), and suggest the potential for prevention. [12]

How is sciatica diagnosed?

Sciatica is largely a clinical diagnosis based on the person’s symptoms and findings on examination. A history of leg pain worse than back pain or pain below the knee should raise suspicion of sciatica. Inquire about the onset and distribution of pain, and associated symptoms such as tingling sensation, numbness, or muscle weakness in the legs.

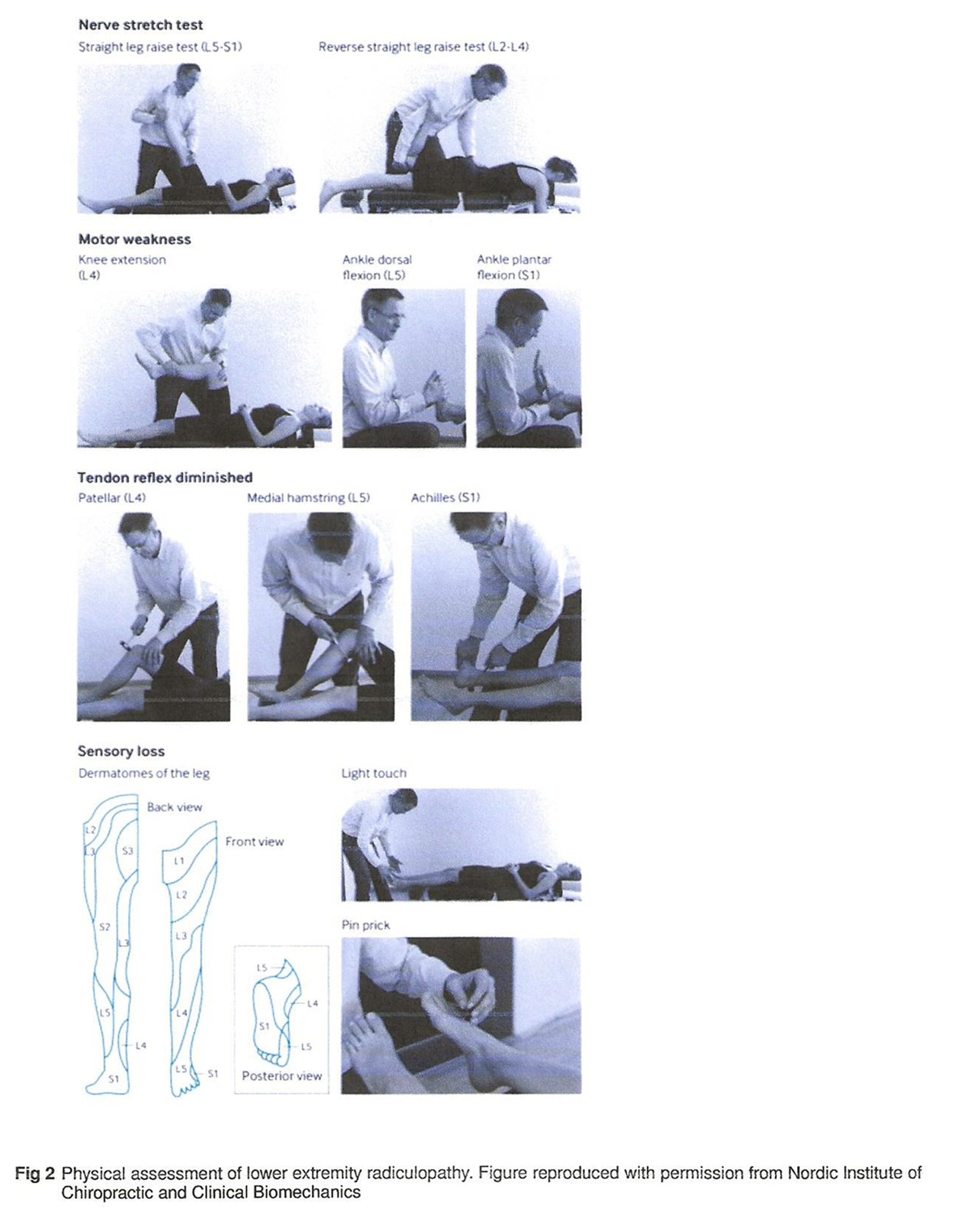

Figure 2 There is no specific test for sciatica but a combination of positive findings on examination increases the likelihood. [13] Figure 2 shows examination for radiculopathy in those patients where sciatica is suspected. A recent cohort study proposed clinical criteria of unilateral leg pain, monoradicular distribution of pain, positive straight leg raise test at <60° (or femoral stretch test), unilateral motor weakness, and asymmetric ankle reflex to predict sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation. [14]

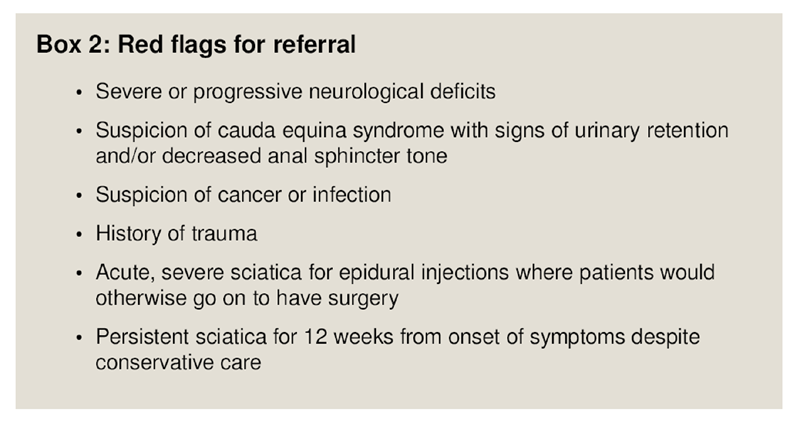

Exclude serious pathology such as cancer, trauma, and infection. Urinary retention and decreased tone of anal sphincter indicate cauda equina syndrome, which should prompt immediate referral.

What is the role of imaging?

Routine imaging is not advised in people with non-specific low back pain with or without sciatica, as per most clinical practice guidelines. [15] It can lead to unnecessary tests, referrals, and intervention, and increased costs. [16, 17] Disc herniation is a common age related finding. A recent meta-analysis (14 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, 3097 individuals) reported disc protrusion in 57% of symptomatic and 34% of asymptomatic individuals and disc extrusion in 7% and 2% of individuals, respectively. [18]

Box 2 Consider imaging if symptoms progress for more than 12 weeks, or if the person has progressive neurological deficits or worsening pain. [4, 19, 20] Box 2 lists red flags for referral. Based on your practice settings, you may request imaging or refer the patient to a specialist. MRI is preferred over computed tomography as it is safer. Radiography is not useful. [21] MRI interpretation is difficult after the initial episode and does not appear to change outcomes. [22]

What is the prognosis?

Most people experience an improvement in symptoms over time with either conservative treatment or surgery. [23] In a five year follow-up of a Dutch randomised controlled trial (231 patients), 8% of patients showed no recovery and 23% reported ongoing symptoms that fluctuated over time. [24] Low back pain with pain radiating to the leg appears to be associated with increased pain, disability, poor quality of life, and increased use of health resources compared with low back pain alone. [10] Severity and duration of symptoms, radiological findings, or patient characteristics do not consistently predict recovery of pain and function with conservative management, as per a systematic review (seven studies). [20]

About 55% of patients with sciatica reported improvement in pain and disability at one year in a recent UK primary care cohort study (452 patients). Treatment was based on clinical guidelines and included physiotherapy sessions. Eleven per cent of patients were referred to secondary care. Fourteen patients had surgery and 21 received spinal injections. Longer pain duration and patient beliefs that the problem would continue were associated with a poor prognosis. [19]

How is it managed?

Symptoms can be distressing and affect daily life and productivity. Acknowledge the person’s concerns and fears. Share information about the natural course of sciatica and reassure them that symptoms usually diminish over time. Discuss treatment options, taking into consideration their preferences, to develop a plan.

Conservative treatment

Initial treatment is aimed at managing pain and maintaining function while the compression and/or inflammation subsides. [2, 3] Encourage patients to remain active and avoid bed rest [2, 3] so that the condition interferes as little as possible with daily life. Ask the person to watch for and report any change in symptoms, such as increasing leg pain or neurological deficits.Exercise and manual therapy Exercise reduces intensity of leg pain in the short term, as per a systematic review (five randomised controlled trials) [25] but the effects are small. Clinical guidelines from the UK, US, and Denmark recommend exercise therapy and mention a range of exercises, but do not indicate whether one type of exercise is better than another. [2–4] Based on your practice settings, general practitioners, chiropractors, or physiotherapists can guide patients on appropriate exercises. Consider the severity of the person’s pain and their ability when recommending exercises. Discuss the options for supervised or group exercise based on what is feasible for your patient.

Manual therapy, such as spinal mobilisation, can be offered alongside exercise, and may be provided by manual therapists, physiotherapists, and chiropractors based on local practice. [2, 3] Acupuncture is not recommended in patients with sciatica. [2, 3]

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) advise against traction and electrotherapies for patients with back pain with or without sciatica. [3]

Medication Pain medications have uncertain benefit for sciatica and can have adverse effects. Discuss their role and use these only very sparsely for a short period of time (weeks rather than months) and in the lowest possible dose for pain relief. [26]

A systematic review (three trials) found that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are no more effective than placebo in improving pain and disability, though there is low quality evidence of overall improvement in patients. Corticosteroids may improve symptoms in the short term (six weeks) compared with placebo, as per a systematic review (two trials). [28] The results were less favourable in two subsequent trials. An increased risk of adverse events is reported with either treatment. [28]

Evidence for the use of paracetamol, benzodiazepines, opioids, and antidepressants for patients with sciatica is limited, and their use is not recommended. [28] The available evidence does not suggest any benefit with anticonvulsants or biological agents [28] compared with placebo.

Spinal injections Guidelines on spinal injections differ in their recommendations. NICE guidelines [3] recommend offering epidural injection of local anaesthetic and steroid in the lumbar nerve root area in people with acute, severe sciatica where they would otherwise be considered for surgery.

The Danish national clinical guidelines do not recommend their use as the beneficial effect was estimated to be very low and only short term based on limited evidence. [2]Surgery

People with persistent pain for more than 12 weeks from the onset of symptoms despite conservative treatment may be considered for surgery. [2] Imaging should confirm lumbar disc herniation at the nerve root level corresponding with findings on clinical examination. Open micro discectomy for removal of disc herniation is the commonest procedure, and minimally invasive surgical techniques such as endoscopic surgery are commonly used. Discectomy rates have increased from a mean of 75 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2007 to 81 in 2015 across 13 European countries as per data from Eurostat, but this varies considerably. [29]

A systematic review [30] (five randomised controlled trials) reports low quality evidence (based on a single trial) that early surgery within 6–12 weeks of radicular pain provided faster relief compared with prolonged conservative care. [31] At one and two year follow-ups, there were no differences in any clinical outcomes between surgery and conservative care. [23, 30, 31] Surgery is also indicated in serious or progressive neurologic deficits such as motor weakness or bladder dysfunction. [32]

A patient’s perspective

It started after an episode of flu. One night, I suddenly had a lot of pain in my leg. The next day, I went to the doctor who told me it was my sciatic nerve that was squeezed. I would have liked more information on what that meant and how long it would take to get better.

During the first three weeks I saw four different clinicians because I had a lot of pain. Only the fourth clinician explained to me what it was and told me that it could take at least a few months to recover. This was useful because then I had a timeframe. I know that the course differs from person to person, but it helps to think, “now I only have four weeks left.”

I have been on sick leave and still am. But now I have started to work a little again. I think it’s getting better. I still have pain in my leg, but it is not quite so fierce, and it is not constant pain any more.

Questions for future research

What is the prevalence of sciatica in different populations such as primary and secondary care, as well as in different age groups and in different professions?

What is the natural course and prognosis of sciatica?

What is the optimal conservative treatment plan, including different treatment modalities and duration?

What are the criteria for surgery and optimal timing to consider surgery?

Additional educational resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE):

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management (PDF)

NICE Guideline, No. 59 2016 (Nov): 1–1067National clinical guidelines for the non-surgical treatment of recent onset lumbar nerve root compression (lumbar radiculopathy).

Danish Health Authority (in English). 2016.

https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2016/~/media/B9D3E068233A4F7E95F7A1492EBC4484.ashxPhysical examination of lower extremity radiculopathy.

Nordic Institute of Chiropractic and Clinical Biomechanics.

http://nikkb.com/research/physical-assessment-of-lower-extremity-radiculopathy [1]North American Spine Society (2012).

Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation With Radiculopathy PDF

(Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

Information resources for patients

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

National clinical guidelines providing recommendations to the public on low back pain and sciatica

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/ifp/chapter/Lowback-pain-and-sciatica-the-care-you-should-expectInternational Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) provides a list of webpages with resources relevant to patients in pain

http://www.iasppain.org/PatientResources.International Society for Advancement of Spine Surgery (ISASS) patient information material on sciatica

https://www.isass.org/for-patients/spineconditions/sciatica/

References:

Valat JP, Genevay S, Marty M, Rozenberg S, Koes B.

Sciatica.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:241-52.Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-surgical Treatment of Patients with

Recent Onset Low Back Pain or Lumbar Radiculopathy

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 60–75National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE):

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management (PDF)

NICE Guideline, No. 59 2016 (Nov): 1–1067Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Konstantinou K, Dunn KM.

Sciatica: review of epidemiological studies and prevalence estimates.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2464-72Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J et al.

What Low Back Pain Is and Why We Need to Pay Attention

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2356–2367

This is the second of 4 articles in the remarkable Lancet Series on Low Back PainRopper AH, Zafonte RD.

Sciatica.

N Engl J Med 2015;372:1240-8Strömqvist F, Strömqvist B, Jönsson B, Karlsson MK.

Surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation in different ages-evaluation of 11,237 patients.

Spine J 2017;17:1577-85Konstantinou K, Dunn KM, Ogollah R, Vogel S, Hay

Characteristics of Patients with Low Back and Leg Pain Seeking Treatment in Primary Care:

Baseline Results from the ATLAS Cohort Study

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015 (Nov 4); 16: 332Hartvigsen L, Hestbaek L, Lebouef-Yde C, Vach W, Kongsted A.

Leg Pain Location and Neurological Signs Relate to Outcomes

in Primary Care Patients with Low Back Pain

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 (Mar 31); 18 (1): 133Ailianou A, Fitsiori A, Syrogiannopoulou A, etal .

Review of the principal extra spinal pathologies causing sciatica and new MRI approaches.

Br J Radiol 2012;85:672-81Cook CE, Taylor J, Wright A, Milosavljevic S, Goode A, Whitford M.

Risk factors for first time incidence sciatica: a systematic review.

Physiother Res Int 2014;19:65-78Stynes S, Konstantinou K, Ogollah R, Hay EM, Dunn KM.

Clinical Diagnostic Model for Sciatica Developed in Primary Care Patients

with Low back-related Leg Pain

PLoS One. 2018 (Apr 5); 13 (4): e0191852Genevay S, Courvoisier DS, Konstantinou K, etal .

Clinical classification criteria for radicular pain caused by lumbar disc herniation:

the radicular pain caused by disc herniation (RAPIDH) criteria.

Spine J 2017;17:1464-71Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, etal .

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview.

Eur Spine J 2018;27:2791-803Wáng YXJ, Wu AM, Ruiz Santiago F, Nogueira-Barbosa MH.

Informed appropriate imaging for low back pain management: A narrative review.

J Orthop Translat 2018;15:21-34Webster BS, Bauer AZ, Choi Y, Cifuentes M, Pransky GS.

Iatrogenic consequences of early magnetic resonance imaging in acute, work-related, disabling low back pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:1939-46BrinjikjiW, Diehn FE, Jarvik JG, etal .

MRI findings of disc degeneration are more prevalent in adults with low back pain than in

asymptomatic controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:2394-9Konstantinou K, Dunn KM, Ogollah R, Lewis M, van der Windt D, Hay

EMATLAS Study Team.

Prognosis of sciatica and back-related leg pain in primary care: the ATLAS cohort.

Spine J 2018;18:1030-40. 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.10.071 29174459Ashworth J, Konstantinou K, Dunn KM.

Prognostic factors in non-surgically treated sciatica: a systematic review.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:208North American Spine Society (2012).

Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation With Radiculopathy PDF

(Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).el Barzouhi A, Vleggeert-Lankamp CL, Lycklama à Nijeholt GJ, etal.

Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group.

Magnetic resonance imaging in follow-up assessment of sciatica.

N Engl J Med 2013;368:999-1007Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, etal .

Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial.

JAMA 2006;296:2441-50Lequin MB, Verbaan D, Jacobs WCH, et al.

Leiden- The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group

Wilco C Peul Bart W Koes Ralph T W M Thomeer Wilbert B vanden Hout Ronald Brand.

Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica: 5-year results of a randomised controlled trial.

Lequin MB, Verbaan D, Jacobs WCH, et al.

BMJ Open 2013;3:002534Fernandez M, Ferreira ML, Refshauge KM, etal .

Surgery or physical activity in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur Spine J 2016;25:3495-512Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, Grooten WJ, etal .

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for sciatica.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;359:CD012382.Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, etal .

Drugs for relief of pain in patients with sciatica: systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ 2012;359:e49710.1136/bmj.e497.Pinto RZ, Verwoerd AJH, Koes BW.

Which pain medications are effective for sciatica (radicular leg pain)?

BMJ 2017;359:j4248Eurostat.

Surgical operations and procedures performed in hospitals by ICD-9-CM: Datamarket; 2018

https://datamarket.com/data/set/28n3/surgical-operations-andprocedures-performed-in-hospitals-by-icd-9

-cm#!ds=28n3!2rsd=s:2rsf=5:6dz9=m.n.5.o.7.8.4.9.c.v.j.6.i.l:7l5k=4&display=line.Jacobs WC, van Tulder M, Arts M, etal .

Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review.

Eur Spine J 2011;20:513-22Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, etal. Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group.

Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica.

N Engl J Med 2007;356:2245-56Deyo RA, Mirza SK.

Herniated lumbar intervertebral disk.

N Engl J Med 2016;374:1763-72

Return to CHIROPRACTIC AND SCIATICA

Since 11-22-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |