Doctors of Chiropractic Working with or within

Integrated Healthcare Delivery Systems:

A Scoping Review ProtocolThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: BMJ Open 2021 (Jan 25); 11 (1): e043754 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Eric J Roseen, Bolanle Aishat Kasali, Kelsey Corcoran, Kelsey Masselli, Lance Laird, Robert B Saper, Daniel P Alford, Ezra Cohen, Anthony Lisi, Steven J Atlas, Jonathan F Bean, Roni Evans, André Bussières

Department of Family Medicine,

Boston University School of Medicine and

Boston Medical Center,

Boston, MA, USA.Introduction: Back and neck pain are the leading causes of disability worldwide. Doctors of chiropractic (DCs) are trained to manage these common conditions and can provide non-pharmacological treatment aligned with international clinical practice guidelines. Although DCs practice in over 90 countries, chiropractic care is rarely available within integrated healthcare delivery systems. A lack of DCs in private practice, particularly in low-income communities, may also limit access to chiropractic care. Improving collaboration between medical providers and community-based DCs, or embedding DCs in medical settings such as hospitals or community health centres, will improve access to evidence-based care for musculoskeletal conditions.

Methods and analyses: This scoping review will map studies of DCs working with or within integrated healthcare delivery systems. We will use the recommended six-step approach for scoping reviews. We will search three electronic data bases including Medline, Embase and Web of Science. Two investigators will independently review all titles and abstracts to identify relevant records, screen the full-text articles of potentially admissible records, and systematically extract data from selected articles. We will include studies published in English from 1998 to 2020 describing medical settings that have established formal relationships with community-based DCs (eg, shared medical record) or where DCs practice in medical settings. Data extraction and reporting will be guided by the Proctor Conceptual Model for Implementation Research, which has three domains: clinical intervention, implementation strategies and outcome measurement. Stakeholders from diverse clinical fields will offer feedback on the implications of our findings via a web-based survey.

Ethics and dissemination: Ethics approval will not be obtained for this review of published and publicly accessible data, but will be obtained for the web-based survey. Our results will be disseminated through conference presentations and a peer-reviewed publication. Our findings will inform implementation strategies that support the adoption of chiropractic care within integrated healthcare delivery systems.

Keywords: back pain; complementary medicine; general medicine (see internal medicine); musculoskeletal disorders; organisation of health services; rehabilitation medicine.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Musculoskeletal conditions, including back and neck pain, are the leading causes of disability worldwide. [1] In the USA, the use of pharmacological treatments, such as opioids and invasive procedures, such as steroid injections and surgery, for low back pain, increased from 1997 to 2010. [2] During the same time period disability and costs from low back pain also increased. [2, 3] In contrast to these patterns of care for spinal disorders, clinical practice guidelines emphasise the use of non-pharmacological approaches before the use of over the counter medications, prescribed medications or invasive procedures. [4–7] Yet patients who seek care in integrated healthcare delivery systems, at specific medical settings such as primary care clinics in hospitals or community health centres, still frequently receive prescribed medications as first line care. [8, 9] Limited familiarity with the efficacy and role of non-pharmacological treatments, few opportunities to practise in the same location as non-pharmacological providers, and inadequate channels of communication between these providers have been identified as important clinician-level barriers that prevent referrals to non-pharmacological treatments. [10–12] Increasing collaboration between primary care providers and providers of non-pharmacological treatment will improve access to non-pharmacological treatments and may improve outcomes.

Doctors of chiropractic (DCs) are trained to manage common spinal disorders, and can provide care that is aligned with international clinical practice guidelines for low back pain, lumbar spinal stenosis, neck pain and headache. [4–7, 13–16 ] Chiropractic care is typically composed of patient evaluation and evidence-based management, including patient education, exercise instruction, spinal manipulation or mobilisation and soft-tissue therapy. [17, 18] Notably, patients who access chiropractic care for their low back pain are less likely than those who initiate care with a primary care provider to receive an opioid medication within 1 year, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and number of chronic conditions. [8, 19]

Although DCs practice in at least 90 countries, chiropractic care is often unavailable in integrated healthcare delivery systems. [20] The majority of DCs practice in private clinics based in the middle-income or upper-income communities [21, 22] of high-income countries. [20] Limited access to chiropractic care may be most pronounced in low-income settings where out-of-pocket costs and a scarcity of community-based DCs may limit use. [23] While primary care providers may encourage their patients to seek chiropractic care, limited exposure to DCs and poor channels of communication may stifle such collaboration. [11] Improved collaboration between medical providers and community-based DCs, or embedding DCs in medical settings, may improve access to evidence-based care for musculoskeletal conditions.

Successful expansion of chiropractic services in the Veterans Health Administration, the largest integrated healthcare delivery system in the United States, has demonstrated that providing chiropractic care within medical settings is feasible. [24] Systematic reviews have also described the delivery of chiropractic care in active duty military settings. [25–27] These reviews have focused on the characteristics of DCs practising in military settings, common conditions managed by DCs and clinical outcomes observed. A recent review evaluated implementation strategies used to increase access to musculoskeletal care within military settings, but not chiropractic care specifically. [28] Review authors found that implementation strategies have focused on developing collaborative models of care, supporting communication between providers and hosting educational meetings. The review also highlighted the need to understand better the steps and details of the implementation process considering their scant description in the included studies. This gap in knowledge highlights the need to further develop and evaluate implementation strategies, defined as the methods to enhance the adoption, implementation, sustainment and scale-up of an evidence-based practice. [29] Furthermore, literature on the provision of chiropractic care in civil medical settings has not been systematically evaluated. Identifying strategies for implementing chiropractic care in low-income settings is particularly needed.

This scoping review aims to map studies of DCs working with or within medical settings, to identify implementation strategies used, and to describe the associated implementation and clinical outcomes. While some barriers to accessing chiropractic care may be unique, we anticipate our findings will be relevant to other providers of non-pharmacological treatments not typically available in medical settings (eg, acupuncturists, psychologists). This scoping review is an important initial step in developing novel and testable implementation strategies that may increase access to non-pharmacological treatments in primary care and other medical settings and decrease the overreliance on pharmacological-based therapies such as opioids.

Methods

Overview

Scoping reviews are a flexible and comprehensive methodology that examine the amount, variety and characteristics of a broad research question. [30] Our review will map literature of DCs working with or within integrated healthcare delivery systems, an emerging area of research. Thus, a scoping review, rather than a systematic review, is appropriate given the relatively unexplored nature of our research question. [31] Our scoping review protocol follows methods recommended by Arksey and O’Malley [32] and Levac et al [33] which have since been formalised by the Joanna Briggs Institute [34] and recent Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. [30] Our approach involves the following six steps:(1) choosing the research question;

(2) identifying relevant studies;

(3) study selection;

(4) charting or extracting the data;

(5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results and

(6) consultation with experts and stakeholders.

Stage 1: research question

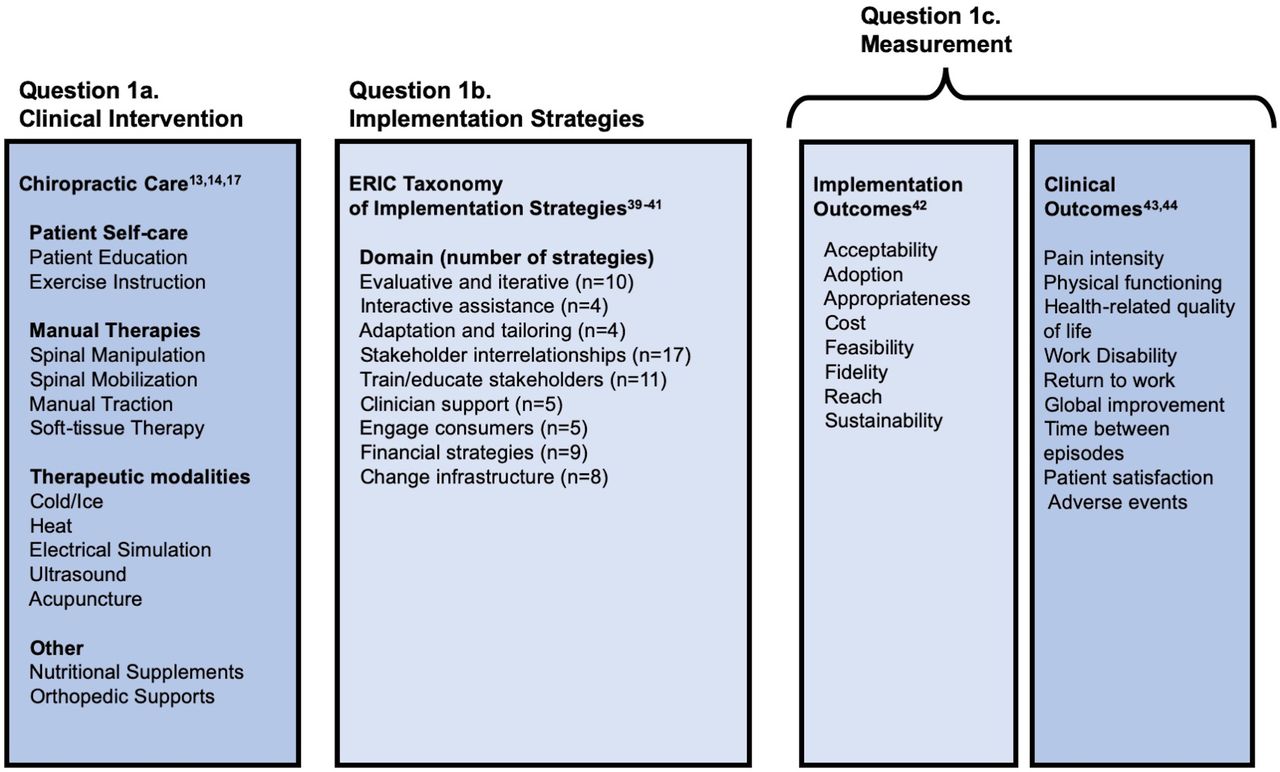

Figure 1 Our study questions are guided by the Proctor Conceptual Model for Implementation Research. [35] The Proctor Conceptual Model identifies three important and distinct concepts in implementation research: the clinical intervention, implementation strategies, and outcome measures. Our overarching research question and three subquestions, which map to the Proctor Conceptual model, are provided below.

These are further described in online supplemental appendix 1 and illustrated in Figure 1.Question 1: ‘What is known from existing peer-reviewed literature about DCs working with or within integrated healthcare delivery systems?’

Question #1 a: What are the characteristics of chiropractic care (eg, location of service, department affiliation, conditions managed, treatments provided) in collaborative models of care that include DCs and medical providers?

Question #1 b: What implementation strategies have been used to initiate or enhance these collaborative models?

Question #1 c: What implementation and clinical outcomes have been studied?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

We will identify English-language studies from 1998 to 2020 in three databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science. The cited references of included studies will be hand searched to identify additional potentially relevant studies. Our preliminary search strategy was developed with the assistance of the head librarian at the Boston University Medical Library (online supplemental appendix 2). Relevant citations will be uploaded into Endnote, V.X8.1 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA).

Stage 3: study selection

Our scoping review will include original studies that report data on DCs who work with or within medical settings. Our final eligibility criteria will be developed post hoc through an iterative team-based approach of reviewing the literature. We will consider concepts used in implementation research, which is defined as the development and evaluation of strategies to integrate evidence-based interventions within specific clinical settings. [36] All members of the study team will complete an open-source course developed by the National Institutes of Health (USA) composed of six modules presenting foundational concepts in implementation research. [37]

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our preliminary set of inclusion criteria is as follows: We will include peer-reviewed original research (ie, experimental, observational and qualitative studies) and knowledge syntheses (ie, systematic reviews) that:(1) describe the practice or initiation of formal collaborative relationships between medical settings and community-based DCs, for example, shared credentialing, continuing education or electronic health record; or

(2) describe the practice or implementation of chiropractic care within medical settings, for example, hospitals, community health centres and

(3) contribute information to one or more of the three domains of the Proctor Conceptual Model, that is, clinical intervention, implementation strategy, or outcome measurement. [35]Examples of medical settings include outpatient hospital, clinic or other practice sites where providers include allopathic and osteopathic physicians, nurse practitioners or physician assistants. As the provision of healthcare has become more complex and multidisciplinary, fewer clinicians (eg, primary care providers) are working in traditional independent solo private practices. [38] As a result, the medical setting of interest for this review broadly encompasses military, veteran and civil integrated healthcare delivery systems. This may include closed model networks such as the Veterans Health Administration and Kaiser Permanente or hospital affiliated networks that include outpatient services such as Partners Healthcare (now named Mass General Brigham) in eastern Massachusetts and Intermountain Healthcare in the Intermountain West of the USA. Common to all of these delivery systems is the provision of a wide range of healthcare services within the provider network.

We will exclude non-English language studies and publications that do not describe original research (eg, guidelines, editorials, commentaries). We will exclude studies that do not involve a medical setting (eg, effectiveness trials based in chiropractic clinics only), as well as studies focusing on medical settings but without the provision of chiropractic care within a collaborative model of care.

All titles, abstracts and relevant full-text articles will be screened independently by two reviewers using the final eligibility criteria. A third reviewer will evaluate conflicts between reviewers. If consensus cannot be reached, a senior investigator will be consulted. The use of a third reviewer and senior investigator will help ensure that appropriate application of eligibility criteria is used and all discrepancies are resolved. The screening process will be facilitated by Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia).

Stage 4: charting and extracting data

A preliminary extraction form and guide developed by our multidisciplinary team are presented in online supplemental appendices 3 and 4, respectively. Two team members will extract information from each study, independently, using this form. This will be an iterative process, and the extraction form will be updated as necessary. The purpose of this process is to collect information that can be mapped back to the Proctor Conceptual Model as illustrated in figure 1. We anticipate collecting information from the following four categories: study characteristics, chiropractic care, implementation strategies and outcome measurement. When this information is incomplete or missing from published reports, we will contact authors of eligible manuscripts to request additional documentation (eg, unpublished reports, protocols).

Study characteristics

We will collect information on study characteristics, for example, study title, authors, country, year published and journal. We will characterise the journal type, for example, chiropractic, complementary and integrative health, general medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation. We will identify the study design and whether a theory or framework related to implementation research or another field was used. We will indicate which stakeholders were involved in data collection (patients, clinicians, other) and how many individuals contributed data.

Chiropractic care

We will report the number of DCs described in each study and describe their characteristics (eg, age, gender, years in practice), and the number of clinics represented in each manuscript. Each clinic or set of clinics will be characterised as serving military, veteran or civil populations. If integration of DCs into multiple medical clinics is described we will indicate whether the clinics are independent of each other or part of the same integrated healthcare delivery system. We will extract a description of each clinical setting and characterise it as primary care (internal or family medicine), physical medicine and rehabilitation, complementary and integrative medicine, orthopaedics, pain medicine or other. We will also identify in each study the hospital or clinic department affiliation of chiropractors if applicable. We will extract information on which conditions were commonly managed by DCs (eg, back pain, neck pain, headache), along with the treatments delivered, including guidance on patient self-care (patient advice and education, exercise instruction), manual therapies (spinal manipulation, spinal mobilisation, manual traction, soft-tissue therapy), acupuncture, therapeutic modalities (cold/ice, heat, electrical stimulation, ultrasound) and other (nutritional supplements, orthopaedic supports). Extraction of information on conditions managed and treatments provided by DCs will include International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes when available.

Implementation strategies

Each study will be characterised as describing a formal or informal implementation strategy or no implementation strategy. The label of ‘formal’ implementation strategy will be applied to studies that use the term ‘implementation strategy’. Formal or informal implementation strategies will be labelled using the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change taxonomy, which includes 9 domains with 73 distinct strategies. [39–41]

Outcome measurement

We will identify studies that present implementation and/or clinical outcomes. Implementation outcomes include acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration and sustainability. [42] Clinical outcomes include pain intensity, physical function, health-related quality of life, global improvement, patient satisfaction and adverse events. [43, 44]

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

Summaries of findings from each extraction form will be entered into a matrix and emerging themes will be discussed at regular team meetings. We will provide a descriptive overview of the eligible individual studies and themes using tables and/or graphical summaries. Separate tables or graphical summaries will be used to organise information on each of the three domains of the Proctor Conceptual Model: description of chiropractic care, implementation strategies and outcome measurement. Within each summary, we will organise studies by setting (active military, veteran, civil) to help demonstrate potential similarities and differences that may impact the implementation process. Altogether, this organisation of data characteristics and themes will facilitate the development of implementation strategies that can be tailored to particular needs of an individual practice or integrated healthcare delivery system. The summary material will form the basis for a report which will be organised according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines. [30]

Stage 6: consultation with stakeholders

The purpose of the consultation phase is to stimulate ongoing feedback and maximise the usefulness of our findings to providers from a range of healthcare disciplines that may collaborate with DCs in routine clinical care. Consultation will involve two modes. First, our core multidisciplinary research team will provide ongoing feedback across all stages of the review. Second, we will conduct a brief online survey with a larger group of stakeholders to generate feedback on our key findings and their implications.

As we developed this protocol, we formed a multidisciplinary team that will continue to offer feedback throughout the conduct of our scoping review. Monthly team meetings and ad hoc document review will serve as a vehicle for ongoing feedback. Team members represent clinical expertise in primary care (internal and family medicine), paediatrics, geriatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, rheumatology, pain medicine, addiction medicine, chiropractic care, and complementary and integrative medicine.

We will conduct a brief cross-sectional web-based survey with a larger group of stakeholders who possess expertise and interest in the purpose of this scoping review. The purpose of this survey is to generate additional feedback on our findings from a broader group of participants. Each of the members of the research team will assist in recruiting members of their disciplines to participate in the survey resulting in a convenience sample of at least 30 participants who represent a diverse range of healthcare fields. Survey questions will be administered before and after participants read a brief report that summarises our key findings. We anticipate including a mixture of closed and open-ended questions, although questions will be determined based on findings from our scoping review and discussion at team meetings.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved at this stage of the project.

Ethics and dissemination

Formal ethical approval is not required to undertake this scoping review of published and publicly accessible literature. However, ethical approval will be obtained before initiating the web-based survey described in the final consultation phase. This cross-sectional survey of stakeholders will facilitate feedback regarding the implications of our review for clinicians, researchers and health system leaders. The completed scoping review will be submitted for publication to a peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary open-access journal, in addition to conferences attended by primary care providers, medical specialists and chiropractors. Our findings will form the basis of implementation strategies to support adoption of chiropractic care within integrated healthcare delivery systems. Ultimately, we anticipate these strategies will improve access to a broader range of evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments for common painful musculoskeletal conditions (eg, acupuncturists, psychologists, others), which may reduce reliance on pharmacologic-based therapies such as opioids.

Supplementary Data

Supplemental material

This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributors

Study concept and design: ER, AK, KC, KM, LL, RS, DA, EC, AL, SA, JFB, RE and AB.

Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: n/a.

Drafting of the manuscript: ER.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ER, AK, KC, KM, LL, RS, DA, EC, AL, SA, JFB, RE and AB.

Statistical analysis: n/a.

Obtained funding: n/a.

Administrative, technical or material support: ER, AK, KC and KM.

Study supervision: ER, RS, LL, RE and AB.

Funding

ER is the recipient of a career development award from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (K23-AT010487), which supported his work on this manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared.

References:

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators.

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 3

10 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015.

Lancet 2016;388:1545–602Mafi, J. N., McCarthy, E. P., Davis, R. B. & Landon, B. E. (2013)

Worsening Trends in the Management and Treatment of Back Pain

JAMA Internal Medicine 2013 (Sep 23); 173 (17): 1573–1581Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al.

US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016

JAMA 2020 (Mar 3); 323 (9): 863–884Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain

Comparative Effectiveness Review no. 169

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; (February 2016)Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-surgical Treatment of Patients with

Recent Onset Low Back Pain or Lumbar Radiculopathy

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 60–75Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Haskett D, Hincapie C, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments for Low Back Pain:

A Guideline From the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (May); 41 (4): 265–293Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al.

Observational Retrospective Study of the Association of Initial Healthcare Provider for

New-onset Low Back Pain with Early and Long-term Opioid Use

BMJ Open. 2019 (Sep 20); 9 (9): e028633Kamper SJ, Logan G, Copsey B, Thompson J, Machado GC, Abdel-Shaheed C, Williams CM, Maher CG, Hall AM.

What is Usual Care for Low Back Pain? A Systematic Review of Health Care Provided to Patients

with Low Back Pain in Family Practice and Emergency Departments

Pain. 2020 (Apr); 161 (4): 694–702Atlas SJ

Management of Low Back Pain: Getting From Evidence-Based

Recommendations to High-Value Care

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 533-534Penney LS, Ritenbaugh C, Elder C, et al.

Primary care physicians, acupuncture and chiropractic clinicians, and chronic pain patients: a qualitative analysis of communication and care coordination patterns.

BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:30Roseen EJ, Conyers FG, Atlas SJ.

Initial management of acute and chronic low back pain: responses from brief interviews of primary care providers.

JACM 2020.Côté P, Wong JJ, Sutton D, et al.

Management of Neck Pain and Associated Disorders: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the

Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European Spine Journal 2016 (Jul); 25 (7): 2000–2022Bussières, AE, Stewart, G, Al Zoubi, F et al.

The Treatment of Neck Pain-Associated Disorders and

Whiplash-Associated Disorders: Clinical Practice Guideline

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Oct); 39 (8): 523–564Côté P, Yu H, Shearer HM, et al.

Non-pharmacological Management of Persistent Headaches Associated with Neck Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European Journal of Pain 2019 (Jul); 23 (6): 1051–1070Rousing R, Jensen RK, Fruensgaard S, et al.

Danish national clinical guidelines for surgical and nonsurgical treatment of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis.

Eur Spine J 2019;28:1386–96Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, Simon NB, Bussieres AE, Mior SA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35Hartvigsen J, French SD. So,

So, what is chiropractic? summary and reflections on a series of papers in chiropractic and manual therapies.

Chiropr Man Therap 2020;28:4Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, et al.

Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt Among Patients with Spinal Pain:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Pain Medicine 2020 (Feb 1); 21 (2): e139–e145Stochkendahl MJ, Rezai M, Torres P, et al.

The chiropractic workforce: a global review.

Chiropr Man Therap 2019;27:36Hurwitz, EL.

Epidemiology: Spinal Manipulation Utilization

J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012 (Oct); 22 (5): 648–654Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, et al.

The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults:

Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 (Dec 1); 42 (23): 1810–1816Heyward J , Jones CM , Compton WM , et al .

Coverage of Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Low Back Pain Among US Public and Private Insurer

JAMA Network Open 2018 (Oct 5); 1 (6): e183044Lisi AJ, Brandt CA.

Trends in the Use and Characteristics of Chiropractic Services

in the Department of Veterans Affairs

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jun); 39 (5): 381–386Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J.

Chiropractic Practice in Military and Veterans Health Care:

The State of the Literature

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009 (Aug); 53 (3): 194–204Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ.

Integration of Chiropractic Services in Military and Veteran Health Care Facilities:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016 (Apr); 21 (2): 115–130Mior S, Sutton D, et al., Daphne To.

Chiropractic Services in the Active Duty Military Setting: A Scoping Review

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2019 (Jul 15); 27: 45Cancelliere C, Sutton D, Côté P, et al.

Implementation Interventions for Musculoskeletal Programs of Care

in the Active Military and Barriers, Facilitators, and Outcomes

of Implementation: A Scoping Review

Implement Sci. 2019 (Aug 16); 14 (1): 82Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC.

Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting.

Implement Sci 2013;8:139Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al.

PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation.

Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al.

Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach.

BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143Arksey H, O'Malley L.

Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework.

Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK.

Scoping studies: advancing the methodology.

Implement Sci 2010;5:69Joanna Briggs Institute.

Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews.

In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015, 2015.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, et al.

Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges.

Adm Policy Ment Health 2009;36:24–34Brownson RC CG, Proctor EK.

Dissemination and implementation research in health.

Oxford University Press, 2018.National Cancer Institute.

Training Institute for dissemination and implementation research in cancer (TIDIRC) OpenAccess. Available:

https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/training-education/tidirc/openaccess.html

[Accessed 21 Jul 2020].Peterson LE, Baxley E, Jaén CR, et al.

Fewer family physicians are in solo practices.

J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:11–12Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al.

A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health.

Med Care Res Rev 2012;69:123–57Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al.

A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project.

Implement Sci 2015;10:21Kirchner JE WT, Powell BJ, Smith JL.

Implementation Strategies.

In: Brownson RPE, Colditz G, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health:

translating science to practice.

Oxford University Press, 2018: 245–66.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al.

Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda.

Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76R.A. Deyo, S.F. Dworkin, D. Amtmann, G. Andersson, et al.,

Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain

Journal of Pain 2014 (Jun); 15 (6): 569–585Chiarotto A, Boers M, Deyo RA, et al.

Core outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials in nonspecific low back pain.

Pain 2018;159:481–95

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 9-24-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |