FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (May); 29 (4): 253–254 ~ FULL TEXT

Claire Johnson, MSEd, DC

Professor,

National University of Health Sciences,

Lombard, IL 60148.

Theories and testable hypotheses are important components of science. Some people are uncomfortable with the term ‘theory,’ possibly because it may be inferred that this term implies quackery by being an unaccepted law or unfounded truth. However, it is important to recognize that theories are essential to scientific method and provide an opportunity for us to test ideas, gather more knowledge, and continue to improve healthcare. If we disallow ourselves to consider and test a theory, then we are restraining the analysis of thought and generation of knowledge. Challenging, testing, accepting, or rejecting theories based upon sound methods allows us to obtain a more complete picture of what is the best way to provide healthcare to our patients. Therefore, instead of fearing theories, we should embrace them.

Historical perspective may be helpful as we reflect upon theories related to manipulation, especially when our perspective is far enough for us to see a more complete picture. Events that are in our recent past may not be seen with enough clarity in order for us to value all that they have to offer. In the present, we are in the middle of the forest, all we can see are the trees and not the forest itself.

In the early decades of the chiropractic profession, some schools of thought focused on the “foot–on–hose” (neuropathology hypothesis) or “bone–out–of–place” (instability hypothesis) models of the subluxation. [1, 2] These simplistic models provided convenient visual depictions for explaining manipulation to students and patients but were not subjected to scientific scrutiny when they were first developed. Although the bone–out–of–place and foot–on–hose models were popular, not all practitioners embraced these as central theories, as there were other theories developed at the same time.

Figure 1 For example, concepts offered 100 years ago in the first published chiropractic textbook, Modernized Chiropractic, [3, 4] demonstrate that there were theories beyond bone–out–of–place and foot–on–hose in the formative years of the chiropractic profession. Although other textbooks were published since then, this first textbook provides a special insight into early concepts in spinal care offered by the profession. Smith et al postulated that, [3] “A simple subluxation is a condition in which the articulating surfaces of a joint are slightly changed though the articulations are still in contact.”

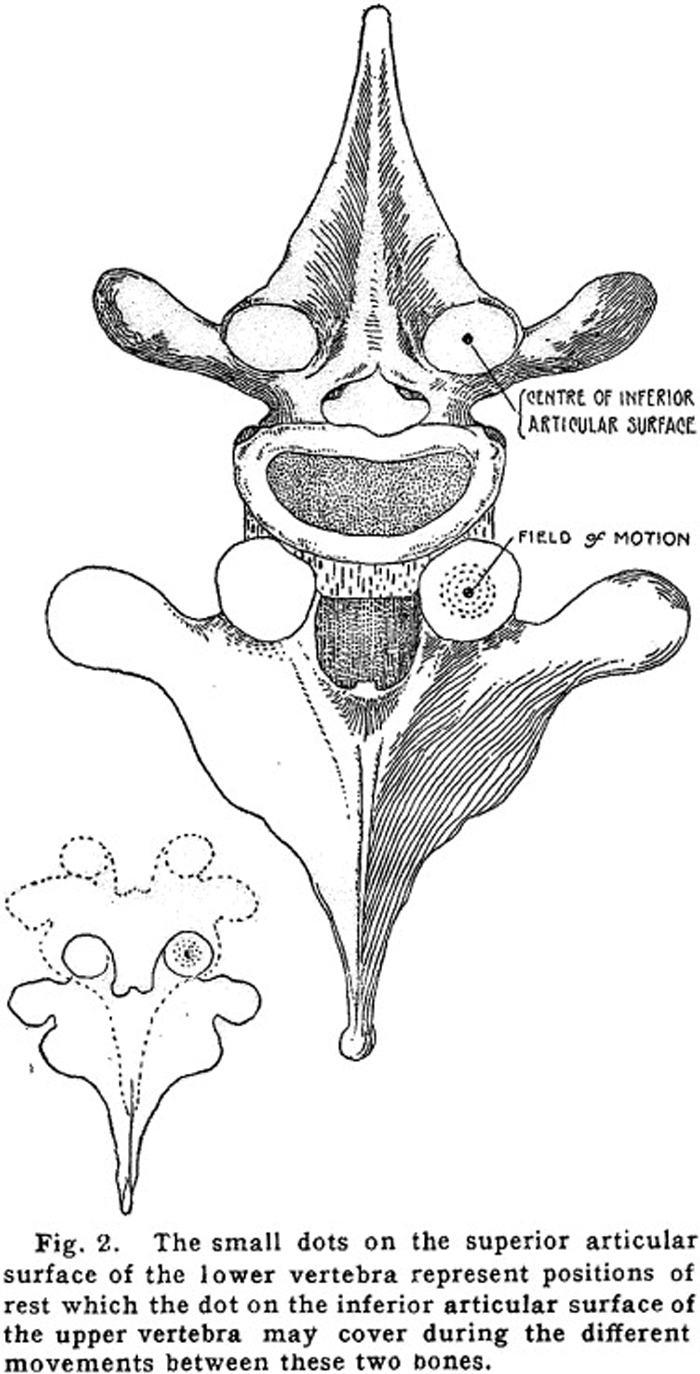

The authors depart from other theories by focusing on dysfunctional motion (Figure 1) [3]: “When a vertebral joint is normal it is capable of a certain definite field of motion over which its articular surfaces travel in performing the various movements to which it is subjected. Having as it does a circumscribed field of motion it must also have a center of motion, and when subluxation occurs it may be likened to a wheel, the hub of which is not in the center.” This theory is testable and may provide a basis for further research on the assessment of spinal function

The authors go on to write [3]:“The object, then, in the reduction of a subluxation is not to push or pull the bone from one fixed, constant, or persistent position to another position just as unchangeable. The real object is to change the center of the field of motion so that the hub of the joint will be where it belongs and this condition can only be brought about by so affecting the malformed structures surrounding the joint as to call into activity that inherent force with which they are endowed, which tends to self preservation and recuperation and whose success is in direct proportion to the degree of activity aroused.”

Again, the authors provide an alternative hypothesis to others presented at the time, albeit that this one would be more difficult to operationalize, even with today's technology. Nonetheless, the idea of a proper axis of motion is a testable theory to which research methods may be applied.

In the first part of the 19th century, new thoughts and approaches to patient health and healing were considered. This was true for all healthcare disciplines. Modernized Chiropractic was published when medical science and research were still in their infancy (eg, vitamins were only on the verge of discovery, and antibiotics were not discovered until more than 20 years later). Medical schools had yet to feel the sharpened blade of the Flexner report that was to come 4 years later. [5] It would be decades before organized efforts and funding were available to develop and implement research related to the science of chiropractic.6 Thus, many of the early chiropractic theories were left unquestioned and untested until recent years.

By looking back 100 years, we are reminded that the chiropractic profession continues to consider multiple theories and approaches to the science and art of healing. Investigating these theories will bring the chiropractic profession closer to understanding the truth. Much is known about where this profession has come from; where it is going is yet to be determined. It is up to the profession to determine its path by embracing the scientific method and testing theories so that we may continue to improve healthcare approaches for our patients.

References:

Leach R.

The chiropractic theories—a textbook of scientific research.

4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

2004;207–34, 251–68.Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM.

Chiropractic: Origins, Controversies, and Contributions

Archives of Internal Medicine 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2215–2224Smith OG, Langworthy SM, Paxson MC

Modernized chiropractic.

Lawrence Press Company,

Cedar Rapids (Iowa) 1906: 17–27Gillet JJ, Gaucher–Peslherbe PL

New light on the history of motion palpation.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996; 19: 52–59Flexner A

Medical education in the United States and Canada: a report to

the Carnegie Foundation for the advancement of teaching.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching,

New York 1910Keating JC, Green BN, Johnson CD

“Research” and “science” in the first half of the chiropractic century.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995; 18: 357–378

Return to SUBLUXATION THEORY

Since 5–29–2023