Are People With Whiplash Associated Neck Pain

Different to People With Non-Specific Neck Pain?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016 (Oct); 46 (10): 894–901

OPEN ACCESS Ricci Anstey, DPT, Alice Kongsted, PhD,

Steven Kamper, PhD, Mark Hancock, PhD

Faculty of Medicine and Health Science,

Macquarie University,

Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Study Design Secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study with cross sectional and longitudinal analyses.

Background The clinical importance of a history of whiplash associated disorder (WAD) in people with neck pain remains uncertain.

Objective To compare people with WAD to people with non-specific neck pain, in terms of their baseline characteristics, and pain and disability outcomes over 1 year.

Methods Consecutive patients with neck pain presenting to a secondary care spine centre answered a comprehensive self-report questionnaire and underwent a physical examination. Patients were classified into either WAD or non-specific neck pain groups. We compared the outcomes of baseline characteristics of the 2 groups, as well as pain intensity and activity limitation at 6 and 12-month follow-up.

Results 2,578 participants were included in the study. Of these 488 (19%) were classified as having WAD. At presentation patients with WAD were statistically different to patients without WAD for almost all characteristics investigated. While most differences were small (1.1 points on an 11-point pain rating scale and 11 percentage points on the Neck Disability Index) others including the presence of dizziness and memory difficulties were substantial. The between group differences in pain and disability increased significantly (P<.001) over 12 months. At 12-month follow-up the patients with WAD on average had approximately 2 points more pain and 16 percentage points more disability than those with non-specific neck pain.

Conclusion People referred to secondary care with WAD were typically more severely affected on self-reported health than those with non-specific neck pain, and also experienced worse outcomes. Caution is required interpreting the longitudinal outcomes due to lower than optimal follow-up rates. Level of Evidence Prognosis, level 2.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Neck pain is a musculoskeletal disorder that is extremely common in the general population and occurs frequently in Western societies. [3, 7, 27, 40] It is estimated that 30% to 50% of the adult population experience neck pain at some point in their lives. [3, 9, 16, 27] The prevalence of chronic neck pain is growing, with an associated increase in costs both personally and to health care systems. [7, 18, 27 Approximately a third of individuals develop chronic symptoms lasting more than 3 months. [20] The onset of neck pain may be insidious or follow trauma. [3, 40]

Whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) is a common type of neck pain [2, 16] in which pain and disability have been reported to persist beyond 3 months in approximately 50% of cases. [6, 32] Typically, recovery rates over the subsequent 12 months are low, [22] and up to 40% continue to report chronic pain and disability 1 year postinjury. [28, 36] Idiopathic neck pain is also a common condition, with a 12-month prevalence of 30% to 50%, although the proportion with activity-limiting pain is probably less than 12%. [17] While pain levels may improve over time, up to 50% do not recover completely over a 1-year period and around a quarter of those who do recover experience recurrences. [5] However, there is controversy as to whether individuals with WAD and individuals with nonspecific neck pain form distinct populations or can be considered together for the purposes of clinical management. [15, 41]

Research into prognostic factors points to considerable overlap between the 2 conditions. [5, 37] In both WAD and idiopathic neck pain, high initial pain and disability levels and longer duration of pain are prognostic of poor outcome. Psychological factors, such as negative expectations, catastrophizing, and cognitions indicative of passive coping style, predict poor outcome in both groups. [5, 34, 37] Cold hyperalgesia and reduced neck range of motion appear to be prognostic in WAD, [5, 38] but have not been implicated in idiopathic neck pain.

Though WAD is often considered a distinct condition from idiopathic nonspecific neck pain, a limited number of studies have directly compared the presentation and outcome in patients with WAD and those with nonspecific neck pain gathered from the same clinical setting. [1, 4, 6, 11, 12, 19, 29] Some of these studies found no systematic differences between WAD and nonspecific neck pain, [21, 40, 41] whereas others observed differences between these patient groups in muscle composition11, [12] and sensory and sensorimotor function, [8] and have shown whiplash injury to be a risk factor for neck pain, [14] resulting in guidelines and recommendations specifically for patients with WAD. [6, 31] Understanding whether patients with WAD have similar or different presentation and clinical outcomes compared to patients with nonspecific neck pain would help to determine the importance of distinguishing between them.

The objective of this study was to identify whether patients who have had neck pain and a history of whiplash (WAD) are different from those who have neck pain and no history of whiplash, from here on referred to as nonspecific neck pain.

The specific study hypotheses were that(1) patients with persistent neck pain and a history of WAD would have different baseline presentations from those with persistent nonspecific neck pain, and

(2) patients with chronic neck pain and a history of WAD would have different outcomes at 6 months and 1 year from those with nonspecific neck pain.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data from the SpineData database. [24] It includes both a cross-sectional study of patient presentation and a longitudinal study of patient outcomes. Informed consent was received and the rights of the participants were protected. The regional ethics committee of Southern Denmark (project ID S-200112000-29) reviewed and approved the protocol for the original study.

Study Setting

Data were collected as part of routine clinical practice in a secondary, nonsurgical, outpatient spine center in the region of Southern Denmark. [24] The spine center performs multidisciplinary, structured physical examinations and treatment planning for patients with spinal pain referred from general practitioners, chiropractors, and medical specialists. Patients referred to the center have received treatment in primary care without a satisfactory outcome. Participants were asked to participate in a follow-up questionnaire at 6 and 12 months. No data were collected on treatments that patients received during the follow-up period.

Data Collection

Data were prospectively collected in the spine center's electronic clinical registry (the SpineData database). [24] Data were collected from both a self-reported questionnaire completed by participants on a touch screen in the waiting area preceding their first consultation, and information entered by clinicians during or immediately after completing a standardized assessment. The clinician- and participant-reported data were entered directly into the SpineData database.

The design and content of the database have previously been described in greater detail. [24]

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All patients who presented to the spine center between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2013 with neck pain as their main complaint and who gave informed consent for their data to be used for scientific purposes were included in the SpineData database at the time of their first visit, as part of the department's clinical routine. For the current study, participants were excluded if no information was registered on whether they had experienced a whiplash injury. Participants were included in the longitudinal study (aim 2) if baseline pain or disability scores at the time of their enrollment in the study were available and if they completed at least 1 follow-up questionnaire at either 6 or 12 months.

Predictor Variables

The clinicians recorded the presence of WAD as part of the initial examination by responding to the question, “Has the patient been exposed to whiplash trauma?” The instructions relating to this question were, “Whiplash trauma is here defined as an acceleration/deceleration of the cervical spine. It is not restricted to movement in a certain plane or to certain mishaps.” Clinicians made this decision based on the information they collected while assessing the patient. If the clinician answered yes, participants were classified as having been exposed to whiplash and considered to have WAD.

Outcome Variables

Outcomes for Cross-sectional Study (Aim 1) We investigated the differences between patients with WAD and patients with nonspecific neck pain on the following baseline measures:

Neck pain intensity: measured with 3 separate questions (neck pain now, worst neck pain in last 14 days, typical neck pain in the last 14 days) by rating the score on a 0-to-10 numeric pain-rating scale (NPRS). The 3 questions were averaged to form a single rating to describe mean pain intensity.

Neck pain frequency: number of days per week neck pain was experienced (dichotomized as all days or not).

Previous episodes of neck pain: scored as yes or no in response to question, “Have you had previous neck pain episodes?”

Activity limitation: the Neck Disability Index (NDI) is a commonly used questionnaire to determine how neck pain affects the participant's daily activities. [30] It consists of 10 items that assess disability in terms of pain, personal care, lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleeping, and recreation, as reported by the participant. The raw score is calculated out of 50 and converted into a percentage (0%, no activity limitation; 100%, complete activity limitation). If participants scored more than 8 items on the questionnaire, the measure was included and the percentage score calculated based on the number of items completed.

Self-reported general health: assessed with the EuroQol health thermometer, by which participants rate their own health at the present time. Scores range from 0 to 100, where 0 is the worst health state and 100 is the best health state. [13]

Anxiety: anxiety was measured on a 0-to-10 numeric rating scale (NRS) in response to the question, “Do you feel anxious?” Zero represented not at all and 10 represented extremely. Anxiety was considered present when values were greater than 6 out of 10. [25]

Depression: 2 screening questions from the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) questionnaire were used to determine if depression was present, [35]

(1) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?” and

(2) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?”Both questions were measured on a 0-to-10 NRS, on which 0 represented never and 10 represented always. Depression was considered to be present if both scores were greater than 6/10. This cutoff score has been validated in this population, relative to the Major Depression Inventory. [25]

Belief about pain becoming persistent: participants answered the question, “In your view, how large is the risk your pain may become persistent?” on a 0-to-10 NRS, with 0 as no risk and 10 as very high risk. Responses of greater than 6/10 were considered as negative recovery expectations.

Dizziness: participants were asked to respond yes or no to the question, “Are you bothered by dizziness?”

Memory difficulties: participants were asked to respond yes or no to the question, “Are you bothered by memory difficulties?”

Morning stiffness: participants were asked to respond yes or no to the question, “Do you have morning stiffness in your neck for more than 1 hour?” Age in years, sex, and duration of current episode in months were also collected.

Outcomes for Longitudinal Study (Aim 2) Neck pain intensity and activity limitation were measured at 6- and 12-month follow-ups using the same methods as described for baseline measures.

Data Analyses

Study Aim 1 Dichotomous baseline characteristics were described as proportion (95% confidence interval [CI]) and continuous baseline characteristics were described as mean (95% CI) or median (interquartile range) when the data were not normally distributed.

Differences between WAD and nonspecific neck pain groups for each baseline characteristic were tested using an independent t test for continuous normally distributed variables and a Mann-Whitney U test for variables with a nonnormal distribution. Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions. Group differences were considered significant at P<.05.

Study Aim 2 Longitudinal models using a linear mixed-model analysis with an independent covariance structure were used to analyze whether patients with WAD had different outcomes from those of patients with nonspecific neck pain in terms of pain and disability at 6 and 12 months. These models took into account that the repeated outcome measures were correlated and could cope well with missing data at 1 follow-up point.39 The outcome measures (pain and activity limitation) were treated as continuous measures. The time variable was introduced into the model as a categorical number of months. Using a categorical time measure, we explore response profiles rather than trends in parametric curves, which we find more clinically interpretable. The primary analysis involved a simple model with no other covariates. We also ran a secondary analysis in which we entered age, sex, and duration of neck pain to assess whether these explained any differences observed between WAD and nonspecific neck pain groups on pain and disability outcomes.

To explore the potential impact of loss to follow-up on any observed group differences between WAD and nonspecific neck pain participants in the longitudinal findings, we performed 2 additional analyses. First, we assessed for differences in baseline prognostic characteristics (sex, age, duration of episode, neck pain intensity, number of previous episodes, NDI score, depression, memory difficulties, dizziness, and recovery expectations) between participants who completed at least 1 follow-up and those who did not. Second, we assessed differences in baseline characteristics between those who did and did not complete follow-up to examine whether any were more pronounced in either the WAD or nonspecific neck pain group by introducing an interaction term in regression models having each of the baseline characteristics as a dependent variable.

Results

Figure 1

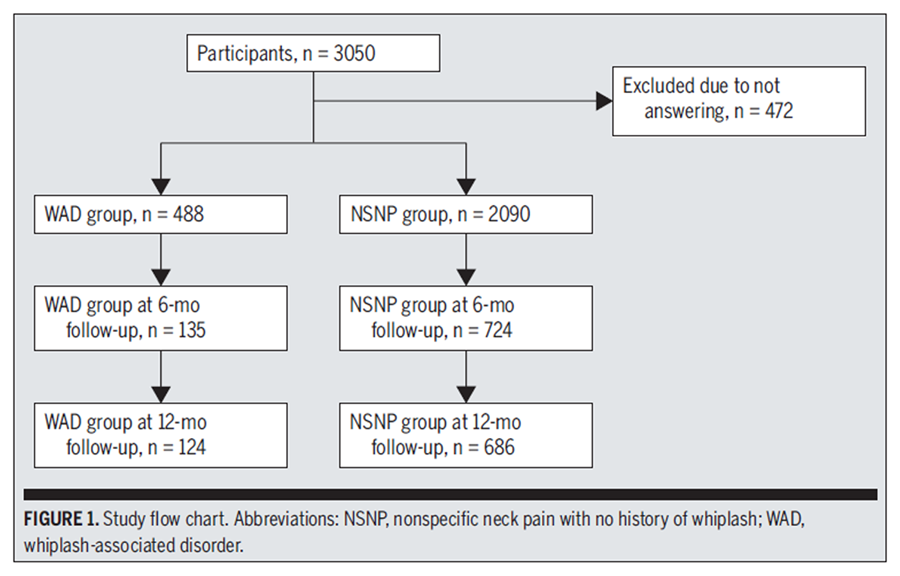

Table 1 A total of 3,050 patients presented with neck pain between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2013. Of these, 472 were excluded from the current study because the data were not sufficient to determine whether WAD was present. Of the 2,578 patients included in the study, 2,090 had nonspecific neck pain and 488 (19%) were categorized as having WAD (FIGURE 1). The majority of participants included were female (61%), with a median age of 49 years.

Study Aim 1: Baseline Differences

Baseline values for the participants with WAD and those with nonspecific neck pain for all variables of interest are reported in TABLE 1. At presentation, patients with WAD were statistically different from patients with nonspecific neck pain for all characteristics investigated (P<.006), except for frequency of neck pain (P = .094). Most between-group differences were small but statistically significant and some, including the presence of dizziness (67% in WAD group and 45% in the nonspecific neck pain group) and memory difficulties (68% in WAD group and 36% in the nonspecific neck pain group), were substantial. Baseline measures consistently indicated greater disease severity in the WAD group.

Study Aim 2: 6- and 12-Month Outcome Differences

Table 2

Table 3

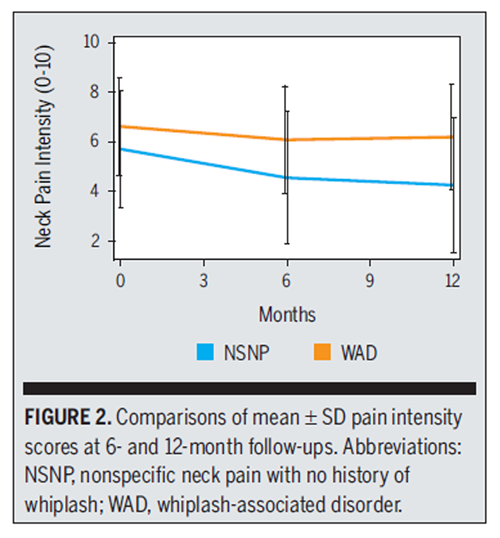

Figure 2

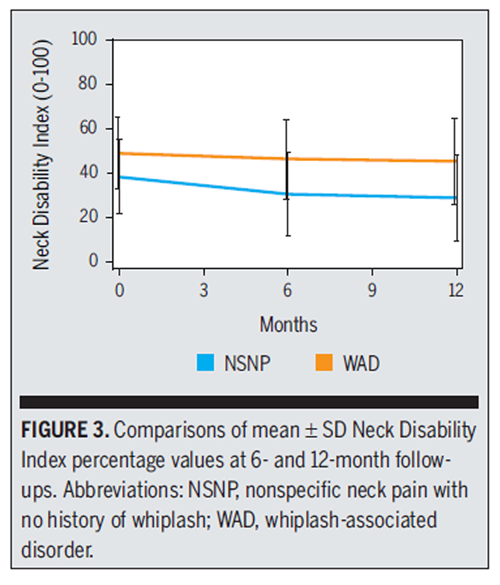

Figure 3 Of 2,578 participants, 1,153 (45%) had baseline data and 1093 (42%) completed either the 6-month or 12-month follow-up for pain intensity and activity limitation and were included in the longitudinal mixed models.

The follow-up rate was slightly higher in the patients with nonspecific neck pain (47%) compared to those with WAD (39%) (P<.001). Noncompleters were on average 5.9 (95% CI: 4.9, 6.9) years younger than completers and had slightly more intense pain (0.21 points; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.40) and more disability (2.4 points; 95% CI: 1.0, 3.8) at baseline than completers. Memory difficulties (odds ratio = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.68, 0.94) and dizziness (odds ratio = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.65, 0.90) were less frequent in completers than noncompleters. None of these differences were significantly different between those with WAD and those with nonspecific neck pain (TABLE 2). There were no associations between completion of follow-up and sex, duration of episode, previous episodes, depression, or recovery expectations.

Pain intensity values in the 2 groups at 6 and 12 months are provided in TABLE 3 and are plotted in FIGURE 2. Based on the longitudinal linear mixed model, statistically significant differences were found between the WAD and nonspecific neck pain groups for pain intensity over the course of follow-up, suggesting that changes in pain intensity over time were different for the 2 groups (P<.001 for the interaction between time and group). Pain intensity for the patients with nonspecific neck pain improved 0.64 (95% CI: 0.20, 1.07) points more than in the WAD group from baseline to 6 months and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.55, 1.45) points more from baseline to 12 months on the 0-to-10 NPRS. Findings were very similar in the second model, indicating that age, sex, and duration of symptoms did not explain these observed differences.

The data for activity limitation (NDI) for the participants in the WAD and in the nonspecific neck pain groups at 6 and 12 months are provided in TABLE 3 and are plotted in FIGURE 3. Based on the longitudinal linear mixed-model analysis, the interaction between time and group was significant (P<.001), suggesting that changes in activity limitation over time were different between the 2 groups. Activity limitation scores for patients with nonspecific neck pain improved 5.7 (95% CI: 3.1, 8.3) percentage points more than in the patients with WAD from baseline to 6 months and 5.5 (95% CI: 2.8, 8.1) points more from baseline to 12 months. Findings were very similar in the second model, indicating that age, sex, and duration of symptoms did not explain these observed differences.

Discussion

Primary Findings

The key finding of this study is that patients reporting a whiplash injury were statistically different from patients with nonspecific neck pain in terms of baseline characteristics and outcomes over 12 months. Baseline between-group differences were mostly small; however, for some measures, including presence of dizziness and memory difficulties, differences were substantial. There were small baseline differences in pain (1.1 points on a 0-to-10 NPRS) and disability (11 percentage points on the NDI), which increased significantly (P<.001) over 12 months. At 12-month follow-up, the patients with WAD had 1.9 points more pain and 17% more disability on average than patients with nonspecific neck pain. These differences can be interpreted in the context of proposed minimally important change thresholds for the NPRS10 (30% of baseline score, which equates to approximately 1.8 in this sample) and NDI (10%–38%).26 In relative terms, patients with WAD had 44% higher pain scores and 54% higher disability scores than those with nonspecific neck pain at 12-month follow-up.

Strengths and Weaknesses

A strength of this study is the large sample size of consecutive patients presenting for care. Also, the data were collected as part of routine care, which increased the generalizability of the findings. Patients and clinicians collecting data were unaware of the hypothesis or question for the current study, minimizing the possibility of reporting bias.

The key limitation of this study is the low percentage of participants who completed follow-up questionnaires and the potential impact of this on study aim 2. We have previously shown that patients from SpineData who completed follow-up were very similar at baseline to those who did not.24 We compared baseline prognostic factors of participants in the current study who completed at least 1 of the follow-ups with those who did not and found only small differences apart from age. Importantly, there were no differences at baseline between patients with WAD and those with nonspecific neck pain in terms of those who completed follow-up and those who did not (TABLE 2). Despite this, it is possible that residual confounding occurred due to unknown variables, thus the results from the longitudinal analysis must be regarded with caution. Given that the respondents were older, had less pain, fewer memory issues, and less dizziness, it is possible this reduced the observed differences for study aim 2.

The definition of WAD and nonspecific neck pain is another potential limitation. Because of the lack of strict diagnostic criteria for WAD, classification depended on patient recall, which might have introduced the risk of misclassification. It is unclear how potential misclassification might have influenced observed group differences. Though the clinicians decided whether the patients' neck complaints were presented in relation to a previous whiplash trauma, they relied on patient recall and self-report during the examination. A further limitation of this study is that some of the baseline characteristics investigated (eg, depression and anxiety) were collected using single-item screening questions rather than multi-item tools. These screening questions have been demonstrated to represent full questionnaires well and are an effective way to gather information when questions on many aspects of health are asked in a clinical setting25; however, loss of accuracy could have affected the precision of the results.

Comparisons With Other Studies

To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated whether individuals with WAD have baseline characteristics different from those of individuals with nonspecific neck pain in a secondary-care setting. Verhagen et al40 combined individual patient data from 3 Dutch studies and 1 English study of participants with mild to moderate nonspecific neck pain and acute whiplash from primary care settings and measured pain and activity limitation at baseline, posttreatment, 6 months, and 12 months. Small differences between the groups of those with WAD and nonspecific neck pain at baseline for pain (0.9; 95% CI: 0.3, 1.4) and NDI (4.6; 95% CI: 1.0, 8.1) were found in the Dutch trials that were similar to the findings of the present study, whereas in the English trial, the groups with WAD and nonspecific neck pain did not differ in presentation. Over the 12-month follow-up, the observed differences became smaller and nonsignificant, while in our study differences between groups increased over 12 months. Possible reasons for the differences between studies are the duration of symptoms (acute versus persistent) and the care setting (primary versus secondary). Scott et al33 assessed differences in pain and disability in patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain and those with chronic WAD using a case-control design. Their findings were very similar to ours, in that the patients with WAD had a pain intensity score on the 0-to-10 NPRS of approximately 1 point higher and an NDI score of approximately 15% higher. They did not follow the patients over time to track clinical course.

A possible explanation for the finding that differences between the groups increased over time may be found in research exploring prognostic factors for the 2 conditions. One of the factors to show a consistent and important association with poor outcome in both groups is high baseline pain and disability severity.5,6,37 Given that the WAD group in our sample had higher mean pain and disability at baseline, it might be expected that this group would do worse over time.

Meanings and Implications

While the underlying pathology in nonspecific neck pain and WAD remains unclear, on average, patients reporting a history of WAD present with a clinical picture of greater severity than those with nonspecific neck pain. While these average differences exist, most are small, suggesting that individuals within each group are not easily distinguished. It remains unclear if the differences we observed are adequate to require different management approaches for these 2 groups. Future studies should explore this, using well-designed subgroup trials. The relatively large baseline differences in dizziness and memory are an interesting finding that could provide insight into the potentially different mechanisms or pathology associated with WAD and nonspecific neck pain. This finding supports previous work suggesting that nonpainful symptoms early after a whiplash injury are related to a poor prognosis.23

The prospects for large improvements in pain and disability in patients with persistent neck pain are modest for both those with nonspecific neck pain and WAD. While those with nonspecific neck pain showed greater improvement over time than those with WAD, the changes in pain and disability, even for those with nonspecific neck pain, were small. The observed changes are at the low end of estimates for minimally important change for pain and neck-related disability, and very close to the minimal detectable change for the instruments used.10,26 This is consistent with current evidence that precise assessment tools and highly effective interventions for chronic neck pain and particularly chronic WAD are lacking.

Conclusion

This study found some potentially important differences, in both baseline presentation and pain and disability outcomes at 1 year, in participants who reported a whiplash injury compared to those with nonspecific neck pain and no history of whiplash injury.

Key Points

Findings

This study determined that individuals referred to secondary care with WAD are as a group more severely affected on self-reported health than those with nonspecific neck pain, and also experience worse outcomes over 12 months.

Implications

It is possible that the differences we observed are adequate to require different management approaches for these 2 groups, and future work should explore this using well-designed studies.

Caution

Caution is required when interpreting the longitudinal outcomes, because follow-up rates were lower than ideal.

REFERENCES

Binder A.

The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash.

Eura Medicophys. 2007;43:79-89.Bogduk N.

The anatomy and pathophysiology of whiplash.

Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1986;1:92-101. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/0268-0033(86)90084-7Borghouts JA, Koes BW, Bouter LM.

The clinical course and prognostic factors of non-specific

neck pain: a systematic review.

Pain. 1998;77:1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0304-3959(98)00058-XCarroll, LJ, Hogg-Johnson, S, Côté, P et al.

Course and Prognostic Factors for Neck Pain in Workers: Results of

the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain

and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S93–100Carroll, LJ, Hogg-Johnson, S, van der Velde, G et al.

Course and Prognostic Factors for Neck Pain in the General Population:

Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force

on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S75–82Carroll, LJ, Holm, LW, Hogg-Johnson, S et al.

Course and Prognostic Factors for Neck Pain in Whiplash-associated

Disorders (WAD): Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010

Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S83–92Cecchi F, Molino-Lova R, Paperini A, et al.

Predictors of short- and long-term outcome in patients with chronic

non-specific neck pain undergoing an exercise-based rehabilitation program:

a prospective cohort study with 1-year follow-up.

Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6:413-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s11739-010-0499-xChien A, Sterling M.

Sensory hypoaesthesia is a feature of chronic whiplash

but not chronic idiopathic neck pain.

Man Ther. 2010;15:48-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2009.05.012Côté P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW.

The association between neck pain intensity, physical functioning,

depressive symptomatology and time-to-claim-closure after whiplash.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:275-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0895-4356(00)00319-XDworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al.

Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials:

IMMPACT recommendations.

Pain. 2005;113:9-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. pain.2004.09.012Elliott J, Sterling M, Noteboom JT, Darnell R, Galloway G, Jull G.

Fatty infiltrate in the cervical extensor muscles is not a feature

of chronic, insidious-onset neck pain.

Clin Radiol. 2008;63:681-687. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. crad.2007.11.011Elliott JM, Pedler AR, Jull GA, Van Wyk L, Galloway GG, O’Leary SP.

Differential changes in muscle composition exist in

traumatic and nontraumatic neck pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:39-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ BRS.0000000000000033EuroQol Group.

EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life.

Health Policy. 1990;16:199-208. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9Freeman MD, Croft AC, Rossignol AM, Centeno CJ, Elkins WL.

Chronic Neck Pain And Whiplash: A Case-control Study of the

Relationship Between Acute Whiplash Injuries

and Chronic Neck Pain

Pain Res Manag. 2006 (Summer); 11 (2): 79–83Grip H, Sundelin G, Gerdle B, Karlsson JS.

Variations in the axis of motion during head repositioning –

a comparison of subjects with whiplash-associated disorders

or non-specific neck pain and healthy controls.

Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2007;22:865-873. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.05.008Guez M.

Chronic neck pain. An epidemiological, psychological and SPECT study

with emphasis on whiplash-associated disorders.

Acta Orthop. 2006;77:2-33. http://dx.doi. org/10.1080/17453690610046486Hogg-Johnson, S, van der Velde, G, Carroll, LJ et al.

The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in the General Population:

Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on

Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S39–51Hoving JL, de Vet HC, Twisk JW, et al.

Prognostic factors for neck pain in general practice.

Pain. 2004;110:639-645. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.002Hoving JL, O’Leary EF, Niere KR, Green S, Buchbinder R.

Validity of the Neck Disability Index, Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire,

and problem elicitation technique for measuring disability

associated with whiplash-associated disorders.

Pain. 2003;102:273-281. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00406-2Huisman PA, Speksnijder CM, de Wijer A.

The effect of thoracic spine manipulation on pain and disability

in patients with non-specific neck pain: a systematic review.

Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1677-1685. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/ 09638288.2012.750689Jull G, Kristjansson E, Dall’Alba P.

Impairment in the cervical flexors: a comparison of whiplash

and insidious onset neck pain patients.

Man Ther. 2004;9:89-94. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00086-9Kamper SJ, Rebbeck TJ, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M.

Course and prognostic factors of whiplash:

a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Pain. 2008;138:617-629. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.019Kasch H, Kongsted A, Qerama E, et al.

A New Stratified Risk Assessment Tool for Whiplash Injuries

Developed from a Prospective Observational Study

BMJ Open 2013 (Jan 30); 3 (1): e002050Kent P, Kongsted A, Jensen TS, Albert HB, Schiøttz-Christensen B, Manniche C.

SpineData – a Danish clinical registry of people with chronic back pain.

Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:369- 380. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S83830Kent P, Mirkhil S, Keating J, Buchbinder R, Manniche C, Albert HB.

The concurrent validity of brief screening questions for anxiety,

depression, social isolation, catastrophization,

and fear of movement in people with low back pain.

Clin J Pain. 2014;30:479-489. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000010MacDermid JC, Walton DM, Avery S, et al.

Measurement properties of the Neck Disability Index:

a systematic review.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:400-417. http://dx.doi. org/10.2519/jospt.2009.2930McLean SM, May S, Klaber-Moffett J, Sharp DM, Gardiner E.

Risk factors for the onset of non-specific neck pain:

a systematic review.

J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:565-572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ jech.2009.090720Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Lin CW, et al.

Comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme or advice for chronic

whiplash (PROMISE): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial.

Lancet. 2014;384:133-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(14)60457-8Olivegren H, Jerkvall N, Hagström Y, Carlsson J.

The long-term prognosis of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD).

Eur Spine J. 1999;8:366-370.Salo P, Ylinen J, Kautiainen H, Arkela-Kautiainen M, Häkkinen A.

Reliability and validity of the Finnish version of the Neck Disability

Index and the modified Neck Pain and Disability Scale.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:552-556. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b327ffScholten-Peeters GG, Bekkering GE, Verhagen AP, et al.

Clinical practice guideline for the physiotherapy of

patients with whiplash-associated disorders.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:412-422.Scholten-Peeters GG, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, et al.

Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders:

a systematic review of prospective cohort studies.

Pain. 2003;104:303-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0304-3959(03)00050-2Scott D, Jull G, Sterling M.

Widespread sensory hypersensitivity is a feature of chronic

whiplash-associated disorder but not chronic idiopathic neck pain.

Clin J Pain. 2005;21:175-181.Shearer HM, Carroll LJ, Wong JJ, et al.

Are psychological interventions effective for the management of neck pain

and whiplash-associated disorders? A systematic review by the Ontario

Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration.

Spine J. In press. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.08.011Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al.

Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care.

The PRIME-MD 1000 study.

JAMA. 1994;272:1749-1756. http://dx.doi. org/10.1001/jama.1994.03520220043029Sterling M.

Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD).

J Physiother. 2014;60:5-12. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.004Sterling M, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, Kamper SJ, Stemper B.

Prognosis after whiplash injury: where to from here? Discussion paper 4.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:S330-S334. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182388523Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R.

Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury.

Pain. 2005;114:141-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. pain.2004.12.005Twisk J, de Boer M, de Vente W, Heymans M.

Multiple imputation of missing values was not necessary

before performing a longitudinal mixed-model analysis.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1022-1028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. jclinepi.2013.03.017Verhagen AP, Lewis M, Schellingerhout JM, et al.

Do whiplash patients differ from other patients with non-specific

neck pain regarding pain, function or prognosis?

Man Ther. 2011;16:456-462. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. math.2011.02.009Woodhouse A, Vasseljen O

Altered motor control patterns in whiplash and chronic neck pain.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-9-90

Return to WHIPLASH

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Since 9-29-2022

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |