Unanticipated Benefits of CAM Therapies for Back Pain:

An Exploration of Patient ExperiencesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2010 (Feb); 16 (2): 157–163 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Clarissa Hsu, Ph.D., June BlueSpruce, M.P.H., Karen Sherman, Ph.D., and Dan Cherkin, Ph.D.

Center for Community Health and Evaluation,

Group Health Research Institute,

Seattle, WA, USA.

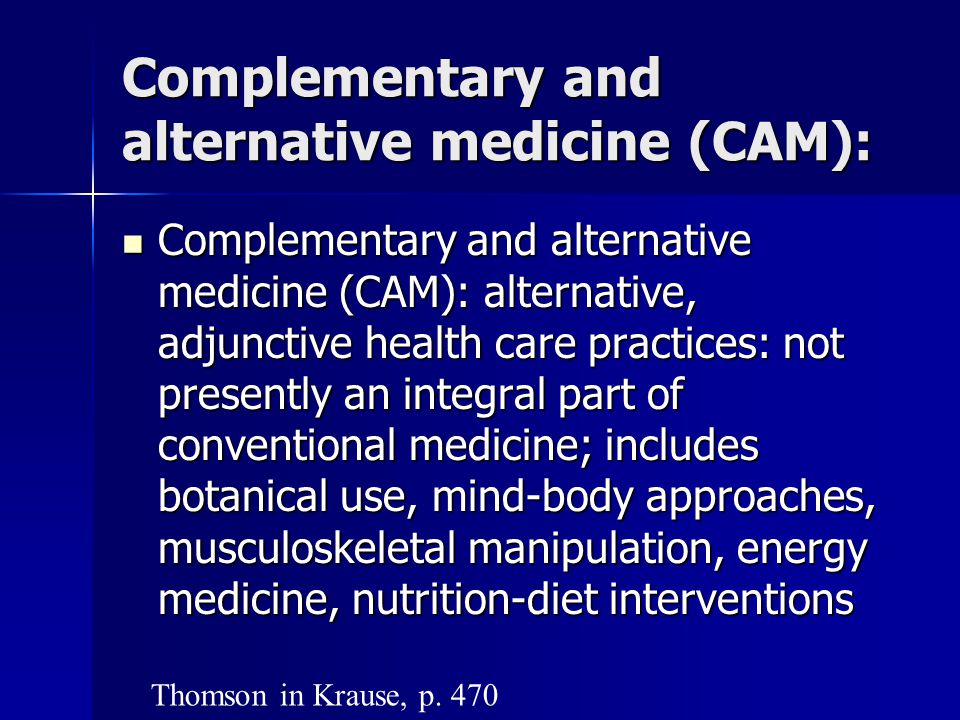

OBJECTIVES: The goal of this research was to provide insight into the full range of meaningful outcomes experienced by patients who participate in clinical trials of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies.

DESIGN: Data for this study were assembled from five randomized trials evaluating six different CAM treatments for back pain. A conventional qualitative content analysis was conducted on responses to open-ended questions asked at the end of telephone interviews assessing treatment outcomes.

SUBJECTS: A total of 884 study participants who received CAM therapies completed post-treatment interviews. Of these, 327 provided qualitative data used in the analyses.

RESULTS: Our analysis identified a range of positive outcomes that participants in CAM trials considered important but were not captured by standard quantitative outcome measures. Positive outcome themes included increased options and hope, increased ability to relax, positive changes in emotional states, increased body awareness, changes in thinking that increased the ability to cope with back pain, increased sense of well-being, improvement in physical conditions unrelated to back pain, increased energy, increased patient activation, and dramatic improvements in health or well-being. The first five of these themes were mentioned for all of the CAM treatments, while others tended to be more treatment specific. A small fraction of these effects were considered life transforming.

CONCLUSIONS: Our findings suggest that standard measures used to assess the outcomes of CAM treatments fail to capture the full range of outcomes that are important to patients. In order to capture the full impact of CAM therapies, future trials should include a broader range of outcomes measures.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Although complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been the focus of extensive research for more than a decade, debates continue about the range of outcomes that should be measured in studies evaluating the effectiveness of these therapies. [1–3] Long argued that “the outcomes of CAM treatment and care need to be understood in terms of a range of specific effects including increased self-awareness and confidence, the quality of the relationship with practitioners,” as well as the resolution of the presenting problem. [2]

Studies evaluating the effectiveness of CAM therapies have found that adding qualitative measures to well-validated quantitative outcomes is critical for capturing the full impact of treatment. [4] Characteristics of CAM that make qualitative measurement important include a focus on the following: wellness and healing of the whole person as a complex living system with physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects; patient outcomes that are typically broad and multidimensional in scope; subtle effects that may only be revealed through overall patterns; and individualized approaches to treatment that vary from patient to patient and also among practitioners. [3–10]

Verhoef, Mulkins, and Boon's survey of CAM researchers, practitioners, and educators identified outcomes that fit into a holistic model of wellness that emphasizes psychologic, social, and spiritual outcomes. [1] The Canadian Interdisciplinary Network of Complementary and Alternative Medicine used this research to construct a conceptual model and database of outcome measures. However, to date there has been limited use of these quantitative measures of holistic outcomes in evaluations of CAM therapies. [4]

The aim of this article is to explore the value of using more holistic outcomes measures when evaluating treatments for back pain. Our analysis explores a number of holistic outcomes experienced by patients that often are missed by the standard quantitative outcome measures typically used to evaluate both CAM and conventional therapies. These findings provide detailed descriptions of key themes in order to provide researchers with insights regarding the identification and design of novel or nontraditional outcomes that capture treatment effects that study participants consider important.

Methods

Table 1 Five (5) studies, all conducted by 2 of the authors, and undertaken in the United States, provided the data for this study. Each was a randomized controlled trial that explored the benefits of one or more CAM therapies (acupuncture, massage, yoga, chiropractic, t'ai chi, and/or mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR]) on back pain. Table 1 provides a brief description of each study. These studies generally found CAM therapies helpful for back pain11 based on the results from the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire12 and a bothersomeness scale [13–15] as the primary outcomes measures. However, the investigators felt that additional positive outcomes were captured in the responses to open-ended questions included in the follow-up interviews. The five studies were chosen for two reasons. First, the data from these studies were readily accessible to our research team because 2 members of the team were the principal investigators for these studies. These team members were familiar with the content of the open-ended responses and felt they merited additional exploration. Second, all five studies were included because they evaluated a range of CAM treatments for the same condition, which the team felt provided a unique data set for analysis.

The data for acupuncture and massage derived from multiple studies and were combined for the analyses (Table 1). Four studies took place in and around Seattle, WA. One of these studies also had a site in Oakland, CA. The fifth study took place in and around Boston, MA.

In every study, participants were asked a series of closed-ended questions about their pain and dysfunction followed by open-ended questions about their perceptions of the effects of the CAM treatment they received. These interviews were administered via phone. Interviewers were trained to ask the open-ended questions as written without probes or requests for clarification. They were instructed to record the answers verbatim while the interview was occurring.

Although most of the studies had multiple interviews over time, we chose to analyze data from only the first post-treatment interview that was conducted within 2 weeks of treatment completion. This first post-treatment interview time point was selected primarily because it was when the respondents would have the most detailed responses to the questions and the greatest recall of the immediate post-treatment experience. Also, subsequent follow-up interviews had smaller numbers of respondents, did not always include open-ended questions, and occurred at different follow-up intervals. The open-ended questions were not asked of participants who were not receiving a CAM therapy, and therefore these study participants were excluded from the overall sample. The wording of the questions varied slightly in the different studies (Table 1).

The analytic phase began with all four authors independently reading through all the open-ended responses from all five studies and identifying quotes that included outcomes not already captured by the closed-ended measures of pain and dysfunction. The team discussed differences in quotes selected for inclusion until consensus was achieved.

Virtually all of the qualitative responses we excluded were responses that duplicated the quantitative measures. We also excluded 29 negative responses that would not have been captured through quantitative measures. These responses included critical statements regarding the practitioner or study logistics (N = 21) and more general negative experiences (N = 8) such as feeling “hot and uncomfortable” or “negative.” Overall, only 5% of participants had negative responses, and most of these would have been captured by quantitative measures. Given these small numbers, we did not feel we had sufficient negative outcomes data to analyze.

The selected responses were then analyzed using conventional content analysis. [16] The coding process started with one team member (J.B.) reading through the responses and drafting a coding scheme. After all team members gave input into the coding scheme, 2 team members (C.H. and J.B.) coded the data using the qualitative analysis software Atlas.ti. Their codes were compared and differences were reconciled through discussion, or, in a few cases, through consultation with other team members. The development of the coding scheme was iterative, resulting in minor changes and additions over time. The end product of the coding processes was the identification of a set of themes. Responses that the coders felt reflected more than one theme were given multiple codes.

The resulting qualitative database was analyzed to determine(1) the relative frequency with which the identified themes were mentioned, and

(2) whether specific themes were more prevalent for some CAM therapies than for others.

Results

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4 A total of 884 participants in the five trials received CAM therapies and responded to the post-treatment follow-up interviews. Of these, 327 (37%) made comments that were included in our analysis (Table 2). The positive outcome themes occurring most frequently were increased options and hope, increased ability to relax, positive changes in emotional states, increased body awareness, and changes in thinking that allowed patients to cope better with their back pain (Table 3). Table 4 provides illustrative quotes for each of these themes.

Increased awareness of treatment options and/or hope (options/hope)

Over 16% of participants responding to the first post-treatment interview spontaneously mentioned increased awareness of and/or confidence in treatment options. This theme was most commonly articulated as being given a new option for pain control. Many stated that they had previously been skeptical that the CAM therapy they received would be effective and/or that they would not have tried the treatment had it not been for enrolling in the study. Phrases like “opened new door,” “provided other tools,” and “opened my mind” were often used. Some participants stated that having this new option meant that they no longer had to use pain medication or consider surgery. Hope was both an explicit and implicit aspect of this options theme. Participants expressed feeling more hopeful that something would work to relieve their pain, as well as more hopeful and confident about their own ability to affect their condition. This theme was most frequently mentioned by those receiving acupuncture.

Increased ability to relax (relaxation)

Relaxation was mentioned by almost 10% of all participants. Most responses were general statements such as “It relaxed me.” However, some responses were more specific, saying that CAM relaxed their back muscles or minds, and one said it relaxed their “entire being.” Some respondents stated that relaxation helped them control pain, and several connected relaxation to breathing and/or meditation. One person who took a yoga class valued “the wind-down time [that] let me carry that feeling of calm and peace with me and apply it to other situations.” Relaxation was mentioned most frequently by those in the yoga, massage, MBSR, and t'ai chi groups, while it was rarely mentioned by those receiving acupuncture or chiropractic.

Positive changes in emotional state (emotional state)

Eight percent (8%) of participants described changes in their emotional states after receiving CAM treatments. The most frequently mentioned effect was reduced stress and worry, sometimes linked with a focus on breathing. Specifically, participants said they had less fear of reinjuring themselves during particular activities and less worry about pain. Other emotional changes included a generally improved psychologic state, being happier or more cheerful, feeling more control over emotional responses to pain and other stressful circumstances, and a greater sense of physical and mental balance. MBSR participants were most likely to mention improved emotional states, something rarely mentioned by those receiving acupuncture and t'ai chi.

Increased body awareness (body awareness)

Eight percent (8%) of participants reported that CAM treatments increased their awareness of their bodies. Some comments were general such as “it gave me [a] different level of awareness” or “it made me more aware of my body.” Others reflected changed perceptions of the body, including more awareness of how different parts are connected and of when pain begins, what causes it, and what one can do about it. Some respondents mentioned awareness of the breath.

For some, body awareness appeared to be more mechanical: attending to posture and movement and being careful to avoid activities and movements that make the pain worse. In other cases, respondents described a deeper sense of being in touch with and listening to the body; one referred to it as “awakening.” Some expressed a holistic view of the body and its connection to how the person lives his or her life. Others referred to the concept of moving energy in the body: “I need to bring energy to where the pain is.” Yoga participants were much more likely than other treatment participants to mention this theme.

Changes in thinking that increased the ability to cope with back pain (changes in thinking)

Another major theme—changes in thinking—was cited by 5% of participants. Comments in this category overlapped those reflecting increased body awareness. Here, the respondents expressed themselves more in terms of cognitive processes, frequently describing changes in their mental models of how the body works, what causes the pain, and what one can do to relieve it. Some said they understood better how a treatment worked. Others cited a changed philosophy or consciousness or a more positive attitude. Still others described using cognitive methods to control pain: “I learned to deal with it when it comes and I've even learned to think it away.” Participants who learned MBSR were most likely to report positive changes in their thinking.

Other positive outcome themes

Several other positive outcomes were brought up by less than 4% of participants. These included improvement in well-being or overall health (“living a better life,” having a “better outlook,” or feeling “more alive”), improvements in other physical symptoms not directly related to their back pain, increased energy, reports of dramatic improvement in symptoms or overall health as a result of CAM treatments, a heightened sense of the connection of mind, body, and spirit after CAM treatment, and increased control over their own health and health care. One (1) in 6 participants in the study that included MBSR mentioned increased mindfulness as a positive outcome.

Discussion

We identified several positive outcomes that participants in CAM trials considered important but were not captured by standard quantitative outcome measures. The most frequently mentioned themes were increased options and hope, increased ability to relax, positive changes in emotional states, increased body awareness, and changes in thinking that increased the ability to cope with back pain.

Some themes were more commonly mentioned by participants receiving particular treatments. Acupuncture participants were more likely to note an increased sense of having a new option for treating their back pains, while yoga participants most often mentioned increased body awareness. MBSR participants talked about positive emotional states, changes in thinking, and mindfulness more frequently than participants in other treatments.

In some cases, these differences were likely the result of the focus of a particular type of treatment. Participants receiving massage, for instance, more often reported an increased ability to relax. The MBSR participants commented on positive changes in emotional state and increased mindfulness, both of which are integral aspects of the training. In other cases, the difference may have been partially attributable to the study design. For example, a selection criterion for most of the acupuncture participants was that they have no prior experience with acupuncture. This lack of exposure to the treatment prior to the study might have contributed to the relatively frequent mention of the options theme among the acupuncture group. Other differences might have been due to variables such as the individual personalities of the therapists hired to carry out the treatments.

This study has a number of limitations. First, these data, although open-ended in nature, were collected as part of a survey instrument. Thus, participants were not expected to provide detailed responses and the interviewers were not permitted to probe for additional information. Also, the documentation of responses was done in real time by interviewers; therefore, many of the responses were likely abbreviated and paraphrased. Based on the difference in the rates of typographical errors and incomplete statements (e.g., statements that end midsentence) found in the data, it was clear that some interviewers were more skilled at transcribing responses than others. These data collection and recording limitations may have resulted in an under-representation of the prevalence of the identified outcomes.

In addition to these limitations, this article has unique strengths. First and foremost, our findings are based on data from five separate studies and six different treatment modalities. The breadth of these data would be hard to replicate in an in-depth qualitative study. Also, the data were volunteered by participants and therefore represent thoughts, ideas, and experiences that they felt were particularly worthy of mention in the context of a telephone survey that primarily focused on closed-ended questions.

This analysis contributes important insights into current conversations regarding how to measure the outcomes and effects of CAM treatments. To date, there has been limited qualitative data collection and analysis in studies of CAM treatment outcomes, especially those outcomes that fall outside the physical domain. Most qualitative work related to CAM effects has focused on expectations of CAM17 or beliefs about the efficacy of CAM treatment among users and nonusers of CAM. [18, 19]

Verhoef et al. recently created a framework and database of appropriate, patient-centered outcome measures for CAM treatments (http://www.outcomesdatabase.org/) based on expert opinion in the field. [1] However, the framework and outcome domains are complex and include many possible concepts to measure. Our findings provide further guidance to researchers interested in identifying the most common outcomes not captured by pain and quality-of-life measures.

Our data suggest that incorporating both closed and open-ended measures of increased options and hope, relaxation, improved emotional states, body awareness, and change in thinking would be an appropriate starting place for documenting a more holistic perspective on meaningful outcomes. We advise that additional work be done to develop more holistic outcomes measures and to further understand and refine the themes we have identified. Such work might include the conduct and analysis of in-depth, open-ended interviews regarding positive outcomes and the testing of new closed-ended questions and instruments designed to better measure holistic outcomes. Another area that deserves further exploration is the effect of expectations and prior use of CAM on these types of holistic outcomes.

Conclusions

We found that a substantial fraction of participants receiving CAM treatments report a broad range of benefits that are not captured by the outcome measures commonly used to assess the benefits of such treatments. Some of these benefits appear to result from the characteristics of particular CAM treatments, while others are more general. We believe that research on the value and efficacy of both CAM and conventional treatments for complex issues such as back pain may be missing important treatment benefits. This situation could be remedied by the inclusion of outcome measures that capture additional meaningful effects such as patients' sense of hope, ability to relax, and increased body awareness.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all the study participants. Their willingness to take part in research studies is essential to our ability generate new insights and knowledge about health and healing. We would also like to thank the practitioners and research staff, whose dedication and professionalism play an important role in the success of research endeavors such as those used in this article.

This research was made possible by awards from the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (U01 AT 001110, R01 AT 001927, R01 AT 00606, R01 AT 00622, R21 AT 001215) and National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (P60 AR 48093). Additional funding was received from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HS 09351), the Group Health Foundation, and the John E. Fetzer Institute. All these sources supported the research in the 5 trials for which we analyzed data.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References:

Verhoef MJ. Vanderheyden LC. Dryden T, et al.

Evaluating complementary and alternative medicine interventions:

In search of appropriate patient-centered outcome measures.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:6–38Long AF.

Outcome measurement in complementary and alternative medicine: Unpicking the effects.

J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:777–786Bell IR. Caspi O. Schwartz GER, et al.

Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: Issues in the emergence of a new model

for primary health care.

Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:133–141Ritenbaugh C. Verhoef M. Fleishman S, et al.

Whole systems research: A discipline for studying complementary and alternative medicine.

Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:32–36Gould A. MacPherson H.

Patient perspectives on outcomes after treatment with acupuncture.

J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:261–268Koithan M. Verhoef M. Bell IR, et al.

The process of whole person healing: “Unstuckness” and beyond.

J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:659–668Oberbaum M. Singer S. Vithoulkas G.

The colour of the homeopathic improvement: The multidimensional nature of the response to homeopathic therapy.

Homeopathy. 2005;94:196–199Verhoef MJ. Casebeer AL. Hilsden RJ.

Assessing Efficacy of Complementary Medicine: Adding Qualitative Research Methods to the "Gold Standard"

Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2002 (Jun); 8 (3): 275–281Sherman KJ. Cherkin DC. Hogeboom CJ.

The diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic low-back pain by traditional Chinese medical acupuncturists.

J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:641–650Verhoef MJ. Mulkins A. Boon H.

Integrative health care: How can we determine whether patients benefit?

J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:S57–S65Sherman KJ. Cherkin DC. Erro J, et al.

Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled trial.

Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849–856Roland M. Morris R.

A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I:

development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain.

Spine. 1983;8:141–144Cherkin DC. Deyo RA. Street JH. Barlow W.

Predicting poor outcomes for back pain seen in primary care using patients' own criteria.

Spine. 1996;21:2900–2907Dunn KM. Croft PR.

Classification of Low Back Pain in Primary Care: Using "Bothersomeness"

to Identify the Most Severe Cases

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 (Aug 15); 30 (16): 1887–1892Patrick DL. Deyo RA. Atlas SJ, et al.

Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica.

Spine. 1995;20:1899–1909Hsieh HF. Shannon SE.

Three approaches to qualitative content analysis.

Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288Richardson J.

What patients expect from complementary therapy: A qualitative study.

Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1049–1053Eliott JA. Kealey CP. Olver IN.

Using complementary and alternative medicine: The perceptions of palliative patients with cancer.

J Palliat Med. 2008;11:58–67McCaffrey AM. Pugh GF. O'Connor BB.

Understanding patient preference for integrative medical care: Results from patient focus groups.

J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1500–1505

Return to ALT-MED/CAM ABSTRACTS

Since 9-28-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |