Cost-effectiveness of Guideline-endorsed

Treatments for Low Back Pain:

A Systematic ReviewThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Spine Journal 2011 (Jul); 20 (7): 1024–1038 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Chung-Wei Christine Lin, Marion Haas, Chris G. Maher, Luciana A. C. Machado, and Maurits W. van Tulder

The George Institute for Global Health and Sydney Medical School,

The University of Sydney,

PO Box M201, Missenden Rd,

Sydney, NSW, 2050, Australia

FROM: Liliedahl ~ JMPT 2010 (Nov)

Commentary From: Chiropractic Cost-Effectiveness By Daniel Redwood, DC

National Guidelines: American Pain Society and

the American College of Physicians (2007) [1]

As has been true of low back pain guidelines worldwide, the 2007 guidelines prepared by a panel of the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians recognized spinal manipulation (over 90 percent of which is delivered by chiropractors) [2] as an effective procedure for both acute and chronic low back pain. This is consistent with the 1994 Guidelines on Acute Lower Back Pain in Adults [3] from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research (AHCPR). Both the APS-ACP guidelines and the earlier AHCPR guidelines were prepared by expert panels based on a full review of all existing research.

(The following) 2011 systematic review [4] of the cost-effectiveness of treatments endorsed in the APS-ACP guidelines found that spinal manipulation was cost-effective for subacute and chronic low back pain, as were other methods usually within the chiropractor’s scope of practice (interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, and acupuncture). For acute low back pain, this review found insufficient evidence for reaching a conclusion about the cost-effectiveness of spinal manipulation. It also found no evidence at all on the cost-effectiveness of medication for low back pain.

REFERENCES:

1. Chou R, Huffman LH; American Pain Society.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 492–504

2. Shekelle PG, Adams AH.

The Appropriateness of Spinal Manipulation for Low Back Pain:

Project Overview and Literature Review

Santa Monica: RAND; 1991. R-4025/1-CCR-FCER.

3. Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G.

Acute Lower Back Pain in Adults.

Clinical Practice Guideline, Quick Reference Guide Number 14.

Rockville: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994.

AHCPR Pub. No. 95-0643.See also our collected: Low Back Pain Guidlines Page.4. Lin C-WC, Haas M, Maher CG, Machado LAC, Tulder MW.

Cost-effectiveness of Guideline-endorsed Treatments for Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review.

European Spine Journal 2011 (Jul); 20 (7): 1024–1038

Healthcare costs for low back pain (LBP) are increasing rapidly. Hence, it is important to provide treatments that are effective and cost-effective. The purpose of this systematic review was to investigate the cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for LBP. We searched nine clinical and economic electronic databases and the reference list of relevant systematic reviews and included studies for eligible studies. Economic evaluations conducted alongside randomised controlled trials investigating treatments for LBP endorsed by the guideline of the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society were included. Two independent reviewers screened search results and extracted data. Data extracted included the type and perspective of the economic evaluation, the treatment comparators, and the relative cost-effectiveness of the treatment comparators. Twenty-six studies were included.

Most studies found that interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, spinal manipulation or cognitive-behavioural therapy were cost-effective in people with sub-acute or chronic LBP. Massage alone was unlikely to be cost-effective. There were inconsistent results on the cost-effectiveness of advice, insufficient evidence on spinal manipulation for people with acute LBP, and no evidence on the cost-effectiveness of medications, yoga or relaxation. This review found evidence supporting the cost-effectiveness of the guideline-endorsed treatments of interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, spinal manipulation and cognitive-behavioural therapy for sub-acute or chronic LBP. There is little or inconsistent evidence for other treatments endorsed in the guideline.

From the FULL TEXT Article

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a common health condition which affects most adults at some point during their lifetime [1]. For most patients in primary care, the source of symptoms cannot be specified and the patient receives the label non-specificLBP [2]. The exceptions are those with back pain associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis [3] and the rare patients whose LBP can be attributed to a disease or condition such as fracture, tumour or infection [4]. Recently, the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society published a joint clinical guideline which recommended the following treatments for non-specific LBP [3]:

Provide evidence-based information on prognosis, advise to remain active, provide information about effective self-care options (referred to as advice for the rest of the paper)

In addition, consider the use of medications with proven benefits

For patients who do not improve, consider the addition of spinal manipulation for acute LBP

For patients who do not improve, consider the addition of interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, massage, spinal manipulation, yoga, cognitive-behavioural therapy or relaxation for sub-acute or chronic LBP

These recommendations are largely in line with other international guidelines [5] and are derived from the vast amount of research regarding the effectiveness of treatments for LBP. For example, the latest issue of The Cochrane Library contains over 30 Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions for LBP [6]. In contrast, until the 2009 British guideline [7], LBP guidelines contained little information on the cost-effectiveness of treatments. This was probably due to the low number of studies available to the developers of the early guidelines. The low number of available studies, together with methodological limitations of the studies and the heterogeneity of the studies, limited any conclusive evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of interventions for LBP [8, 9].

LBP incurs substantial treatment and loss of productivity costs internationally [10]. In the United States, healthcare costs among people with back pain increased by 65% from 1997 to 2005, more rapidly than healthcare costs among people without back pain and the overall healthcare costs [11]. Given that the guidelines considered a range of interventions to be effective, the efficiency of treatment will be improved if their relative cost-effectiveness is also considered. As the number of published economic evaluations of interventions for LBP is increasing, it may now be possible to consider evidence of cost-effectiveness when making recommendations about treatment. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for non-specific LBP.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We conducted a systematic search for economic evaluations (i.e. cost-minimization, cost-effectiveness, cost-utilization or cost-benefit analysis) [12] conducted alongside randomised controlled trials in adults with non-specific LBP. Treatments endorsed in the clinical practice guideline of the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society were eligible for inclusion (i.e. advice, medication, spinal manipulation for acute LBP, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, massage, spinal manipulation, yoga, cognitive-behavioural therapy or relaxation for sub-acute or chronic LBP) [3], except when these treatments were implemented after spinal surgery. To be included, studies had to relate the costs of the interventions to the effects of the interventions, for example by reporting an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). There was no language restriction.

We searched six clinical (Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PsychINFO and PEDro) and three economic (EconLit, NHS EED and EURONHEED) databases from inception to 1 June 2010. The reference list of relevant systematic reviews and included studies was also searched. Search terms were derived from the search strategies of the Cochrane Back Review Group

(http://www.cochrane.iwh.on.ca/pdfs/CBRG_searchstrat_Sept08.pdf)

and the British National Health Services Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

(http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/nhseedfaq02.htm).

As an example, the complete search strategy for EMBASE is in Appendix.

Study selection and quality assessment

Each review process (screening, risk of bias assessment and data extraction) was conducted by two independent reviewers, with differences resolved first in discussion, and then (if necessary) by arbitration by a third, independent reviewer. In selecting eligible studies from the search results, first the titles, then abstracts (if available), and then full papers were screened. For the included studies, we used the criteria from the Cochrane Back Review Group [13, 14] to assess the risk of bias of the trial design, and the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC-list) [15] to assess the methodological quality of the economic evaluation. Studies that scored 6 or more out of a total of 11 on the risk of bias assessment were considered as having a low risk of bias. [16] All publications related to the included studies (e.g. published protocol or clinical outcomes paper) were used to inform the risk of bias assessment and data extraction (see Appendix).

Data extraction, synthesis and analysis

Data were extracted using a customized data extraction sheet, and included: the type and perspective of the economic evaluation, treatment comparators, year/s, country and currency of the study, and results of the relative cost-effectiveness of the treatment comparators, which was the primary outcome of interest. As we could not locate an agreed cost-effectiveness threshold for the United States, we used the threshold set by the United Kingdom (UK)’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) as an indicator for cost-effectiveness. [17] That is, if a treatment had an ICER lower than £20,000–£30,000 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) gained, the treatment was deemed as relatively cost-effective compared to an alternate treatment. Where a treatment incurred significantly lower costs and was statistically significantly more effective compared to an alternate treatment, the treatment was considered as “dominant”.

Results

Characteristics of included trials

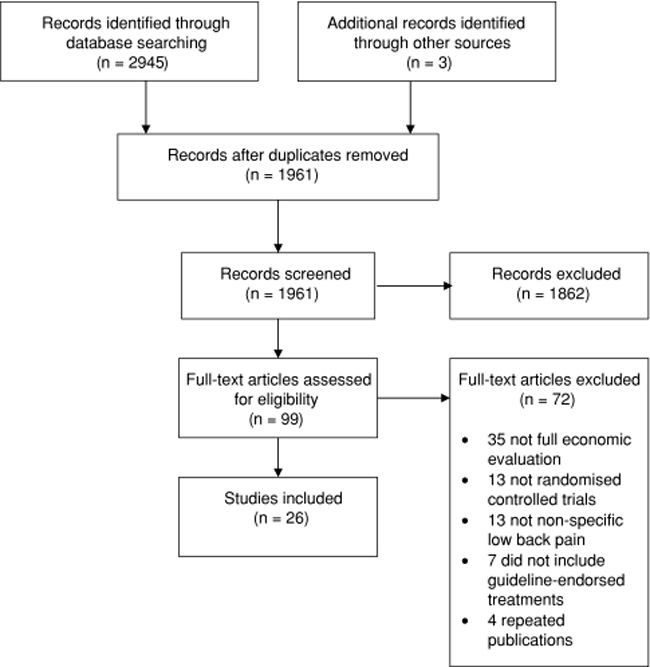

Figure 1 A total of 26 studies were included after screening the 1961 records found in the search (Figure 1). Results of two separate studies [18, 19] were reported in one paper [20]. These studies had almost identical design features so are referred to as “Strong et al.” in the current paper. For two of the included studies, results of the one- and two-year follow-up were published separately. [21-24] Most studies conducted a cost-effectiveness and/or cost-utility analysis. One study conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis as well as a cost-benefit analysis. [25] Four other studies conducted a cost-benefit analysis [26-29] and two studies conducted a cost-minimization analysis. [30, 31] One study did not clearly state the type of economic evaluation undertaken, but we consider this to be a cost-effectiveness analysis due to the outcomes reported. [21, 22]

Most studies recruited participants with at least 4–6 weeks (sub-acute) or greater than 12 weeks (chronic) of LBP. The only exceptions were two studies which recruited participants of a mixed duration of symptoms [30, 32] two which did not specify the duration of symptoms [20], and one which recruited participants sick listed for less than 2 weeks due to LBP [31]. Most studies were conducted in the UK [32-40] or other European countries [21–24, 26–29, 31, 41–45]; three studies were conducted in the United States [20, 30] and two in Canada. [25, 46] All studies were published in English.

Risk of bias of the trial design

Table 1 Just over half (n = 13) of the studies had a low risk of bias. Five of the studies did not report adequate randomization procedures [19, 20, 40, 41], nine did not have adequate allocation concealment [18–20, 23, 24, 29, 31, 39, 41, 44, 46] and none of the studies used assessor blinding (Table 1).

Quality of the economic evaluation

Eleven studies scored 17 or more out of 19 on the CHEC-list. Seven studies did not state the economic perspective adopted [21, 22, 29–32, 35, 41]. An incremental cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted in all but 2 of the 19 cost-effectiveness or cost-utility studies. [23, 24, 41] Three of the nine studies which had a follow-up period of greater than 1 year did not use discounting. [23–25, 30] Other methodological issues are outlined in the following sections describing the evidence for each treatment (Table 1).

Advice (provide evidence-based information on prognosis, advise to remain active,

provide information about effective self-care options)

Table 2 A total of nine studies were included (Table 2). Six studies compared advice to another treatment [20–22, 27, 38, 46], and three compared adding another treatment to advice with advice alone [23, 24, 26, 36]. Regardless of the comparison and the economic perspective adopted, results regarding the cost-effectiveness of advice were inconsistent across the studies (Table 2). Four studies suggested that advice may be more cost-effective than treatments received in primary care [21, 22, 27] or a book on back pain care [20], but other studies reported a cost-effectiveness ratio or cost-benefit outcome which favoured adding naturopathic care [46], graded activity [26],or manipulation and stabilizing exercises [23, 24] over advice alone, or physiotherapy over advice. [38] In a study comparing adding manipulation and exercises to advice alone [23, 24], it is unclear why the reported cost-effectiveness ratio was positive for pain but negative for disability, given that costs were identical and the direction of benefits was the same for both outcomes.

There were methodological issues regarding the identification and measurement of costs in five of the eight studies. One study [46] undertook their analysis from the societal perspective, but did not collect the costs of visits to doctors, or secondary or tertiary care. It was unclear why some of the costs reported had a negative value, and their follow-up period (6 months) may be too short to fully capture the economic consequences of sub-acute or chronic LBP. Two studies [20] undertook their analysis from the health insurer’s perspective but excluded the costs of inpatient care. Both studies which conducted a cost-benefit analysis [26, 27] had a 3-year follow-up, but collected only the costs incurred in the first year. One of these studies did not state the methods used to value the costs. [27]

In addition, consider the use of medications with proven benefits

No study compared the cost-effectiveness of any medication in managing LBP. This included the first-line recommendation of acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, more potent analgesics such as opioids or tramadol, and herbal therapies.

For patients who do not improve, consider the addition of spinal manipulation

for acute LBP

Only one study investigated the cost-effectiveness of spinal manipulation in people with acute LBP. [31] Results of this cost-minimization study showed that while spinal manipulation was not the cheapest treatment option, the differences in costs over 1 year compared to care provided by a general practitioner (GP care) or exercise appeared small (total cost in Swedish crowns, price year not stated, for spinal manipulation = 49,076, GP care = 50,834 and exercise = 45,423). However, there was no formal statistical comparison and this study had incomplete cost identification (only the costs of study treatment, investigations and operations were collected as the direct costs).

For patients who do not improve, consider the addition of interdisciplinary rehabilitation,

exercise, acupuncture, massage, spinal manipulation, yoga, cognitive-behavioural

therapy or relaxation for sub-acute or chronic LBP

Table 3 Fifteen studies investigated the cost-effectiveness of interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, spinal manipulation or cognitive-behavioural therapy. These interventions were compared to conventional physiotherapy [29, 32, 33, 43], GP care [25, 28, 30, 35], spinal surgery [29] or walking [39], or as an additional treatment to advice [23, 24, 26], GP care [34, 36, 40] or inpatient rehabilitation. [44] Regardless of the comparisons and the perspectives adopted, all but two studies [30, 32] found that these interventions were cost-effective compared to the treatment alternatives (Table 3). In particular, Schweikert et al. [44] found that adding cognitive-behavioural therapy to inpatient rehabilitation dominated over inpatient rehabilitation alone (ICER = –126,731 in 2001 Euro per QALY gained), and Torstensen et al. [29] found that medical exercise therapy dominated over walking (cost benefit = 906,732 in Norwegian Kroner, price year not stated). However, Schweikert et al. [44] had a follow-up of 6 months, which may be too short to adequately measure the economic consequences of chronic LBP. Torstensen et al. [29] did not specify the perspective of the economic evaluation. Given that people in the walking group incurred no costs, it is likely that this study conducted the economic evaluation from a narrow perspective, including the costs of the study treatment only.

Four studies compared interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, spinal manipulation and cognitive-behavioural therapy to each other. Critchley et al. [33] found that a pain management programme using cognitive-behavioural principles was likely to be more cost-effective compared to exercise from the healthcare sector’s perspective. Smeets et al. [42] found that, from a societal perspective, the combination of exercise with graded activity and problem solving was not cost-effective compared to exercise or graded activity and problem solving alone (e.g. ICER for exercise compared to combined group = 35,060 in 2003 Euro per QALY gained, ICER for graded activity and problem solving compared to combined group = dominant). In contrast, combining both manipulation and exercise with GP care was relatively cost-effective (ICER = 3,800 per QALY gained) compared to manipulation plus GP care (ICER = 4,800 per QALY gained), or exercise plus GP care (ICER = 8,300 per QALY gained) from the UK healthcare sector’s perspective (in 2000–2001 GBP). [40] One study showed that receiving an operant conditioning programme with group discussion or a cognitive behavioural component and relaxation incurred lower direct and indirect costs compared to waiting list then receiving the operant conditioning programme, but did not report an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis. [41]

Witt et al. found that adding acupuncture to physician care had a low ICER compared to physician care alone from the societal perspective (€ 10,526 per QALY gained in 2006 Euros, or GBP 7839.29 converted using purchasing power parities www.oecd.org/dataoecd/61/54/18598754.pdf) [45]. But this result is limited by methodological issues. For example, the costs collected (provided by health insurance funds) may be incomplete for the perspective adopted (societal), the methods of cost valuation were not reported, and data were collected immediately after the treatment period with no other follow-up. Ratcliffe et al. [37] showed that acupuncture had a low ICER compared to GP care from the healthcare sector perspective (4,241 in 2002 to 2003 GBP per QALY gained, 95% CI = 191–28,026), and was dominant over GP care from the societal perspective.

Hollinghurst et al. [34] investigated the cost-effectiveness of massage over a 1-year period. Compared to GP care, massage incurred higher costs from the healthcare sector’s perspective and was less effective (QALY gained = –34,473 in 2005 GBP). But adding exercise and behavioural counselling to massage improved the cost-effectiveness of massage (ICER compared to GP care plus exercise and behavioural counselling = 5,304 in 2005 GBP). No studies investigated the cost-effectiveness of yoga or relaxation.

Discussion

We found 26 economic evaluations conducted alongside randomised controlled trials that investigated the cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for non-specific LBP. There were inconsistent findings regarding the cost-effectiveness of advice, but studies generally showed that interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, spinal manipulation and cognitive-behavioural therapy were relatively cost-effective for people with sub-acute or chronic LBP. Results from single studies suggested that massage alone was unlikely to be cost-effective, and that the cost-effectiveness of spinal manipulation for acute LBP was unclear. No studies investigated the cost-effectiveness of medication, yoga or relaxation as treatments for LBP.

The eight studies which investigated advice did not yield consistent or conclusive evidence about its relative cost-effectiveness. Interestingly, these studies also reported inconsistencies in the effectiveness of advice compared to other treatments. In contrast, the American clinical guideline made a strong recommendation for advice to stay active based on moderate-quality evidence [3]. Other guidelines also recommend advice to stay active [5]. One reason for the difference between our findings and guideline recommendations may be that in the guidelines, the recommendations were based on evidence from systematic reviews which compared advice to stay active with bed rest, which is considered potentially harmful for this population [47]. The studies included in this review compared advice to a variety of treatment alternatives, but not bed rest.

We did not pool the results in the studies that compared advice, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, spinal manipulation and cognitive-behavioural therapy for sub-acute or chronic LBP, as may occur in a systematic review of treatment effectiveness. This is due to the heterogeneity in study treatments, as well as differences in economic perspectives and settings. The underlying assumption for pooling in a systematic review of treatment effectiveness is that results obtained in one country are generalisable to a similar population in a different setting or country. Whilst it seems reasonable to assume that individuals or groups are likely to react in the same way to a particular intervention, no matter where they live, comparing economic data across different settings or countries is not as straightforward due to differences in the structure and organization of healthcare systems. For example, in some countries patients may have direct access to medical specialists or other healthcare providers while in other countries patients need a referral from a primary care physician. Access to some care providers may be limited in some countries where this care is not provided by a public healthcare system or is not reimbursed by an insurance scheme. Cost data may also be sensitive to the funding and reimbursement arrangements in a particular healthcare system. However, despite this complexity, there are emerging guidelines on the transferability of economic evaluations [48–50].

We used the NICE threshold to provide an indication of the cost-effectiveness of treatment, because the NICE threshold is commonly available. However, it should be noted that there is no consensus about the maximum costs per QALY gained that would be acceptable, and recent evidence indicates that the cost-effectiveness threshold may vary depending upon the severity and the prevalence of the disease. We used the treatments endorsed by the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society as guideline-endorsed treatments, because at the time of study conception the American guideline was one of the most recent guidelines. A recent review shows that treatments endorsed by the American guideline are in line with other guidelines [5]. The only area of contention is in the use of spinal manipulation where, unlike the American guideline, some countries do not recommend spinal manipulation for LBP. Interestingly, our systematic review considers evidence purely from a cost-effectiveness perspective and shows some evidence of cost-effectiveness when using spinal manipulation in sub-acute to chronic pain.

There were some methodological issues which limit the interpretation of our findings. These include the incomplete identification and measurement of costs, which reduces the rigour of the results. Three studies had follow-up periods that are likely to be too short to fully appreciate the economic consequences for the chronic population under investigation [44–46]. Based on recent large cohort studies on the prognosis of acute [51] and chronic [52] LBP, we recommend a follow-up period of at least 3 months for acute LBP and at least 12 months for chronic LBP. In addition, to help readers assess the extent to which the results of studies are applicable to different healthcare systems, we recommend that economic evaluations report unit costs as well as reporting a breakdown of costs and resource utilization. Eleven of the 26 included studies provided a table of unit costs [21, 22, 33, 34, 37–40, 42, 43, 46, 53].

Considering the evidence regarding both relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness when making treatment recommendations means that the endorsed treatments are both beneficial to patients and efficient in terms of healthcare resources. The small number or lack of economic evaluations for some guideline-endorsed treatments means well-conducted economic evaluations are required to strengthen the evidence-base of treatments for LBP. However, evidence to date indicates that guideline-endorsed treatments such as interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise, acupuncture, spinal manipulation and cognitive-behavioural therapy for sub-acute or chronic LBP are cost-effective. Although advice to stay active is endorsed in the guideline, and evidence regarding its cost-effectiveness compared to other interventions is inconsistent. In addition, there is little or no high-level evidence about other guideline-endorsed treatments: medication, spinal manipulation for acute LBP, and massage, yoga or relaxation for chronic LBP.

Acknowledgments

CL and CM are funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia. LM is funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Brazil.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References:

Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C.

Low Back Pain: What Is The Long-term Course? A Review of Studies of General Patient Populations

European Spine Journal 2003 (Apr); 12 (2): 149–165Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S.

Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain.

BMJ. 2006;332(7555):1430–1434.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, Owens DK:

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline

from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J.

Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients

presenting to primary care with acute low back pain.

Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(10):3072–3080Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C.

An Updated Overview of Clinical Guidelines for the Management

of Non-specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care

European Spine Journal 2010 (Dec); 19 (12): 2075–2094The cochrane library, issue 3 2009.

http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/mrwhome/106568753/HOME?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

Accessed 22 September 2009Savigny P, Kuntze S, Watson P, et al.

Low Back Pain: Early Management of Persistent Non-specific Low Back Pain PDF

London, UK: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and

The Royal College of General Practitioners; 2009.van der Roer N, Goossens ME, Evers SM, van Tulder MW.

What is the most cost-effective treatment for patients with low back pain? A systematic review.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19(4):671–684.Dagenais S, Roffey DM, Wai EK, Haldeman S, Caro J.

Can cost utility evaluations inform decision making about interventions for low back pain?

Spine J. 2009;9(11):944–957.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S.

A Systematic Review of Low Back Pain Cost of Illness Studies

in the United States and Internationally

Spine J 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 8–20Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Comstock BA, Hollingworth W, et al.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656–664Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL.

Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes.

3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M,

Editorial Board Cochrane Back Review Group 2009 updated method guidelines

for systematic reviews in the cochrane back review group.

Spine. 2009;34(18):1929–1941van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L,

Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group Updated

method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group.

Spine. 2003;28(12):1290–1299Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A.

Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations:

Consensus on health economic criteria.

Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–245van Tulder M, Suttorp M, Morton S, Bouter L, Shekelle P.

Empirical evidence of an association between internal validity and effect size

in randomized controlled trials of low-back pain.

Spine. 2009;34(16):1685–1692Appleby J, Devlin N, Parkin D.

Nice’s cost effectiveness threshold.

BMJ. 2007;335(7616):358–359Moore JE, Von Korff M, Cherkin D, Saunders K, Lorig K.

A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral program for enhancing back pain

self care in a primary care setting.

Pain. 2000;88(2):145–153Von Korff M, Moore JE, Lorig K, Cherkin DC, Saunders K, González VM, Laurent D, Rutter C, Comite F.

A randomized trial of a lay person-led self-management group intervention for

back pain patients in primary care.

Spine. 1998;23(23):2608–2615Strong LL, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Moore JE.

Cost-effectiveness of two self-care interventions to reduce disability associated with back pain.

Spine. 2006;31(15):1639–1645Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Mutanen P, Roine R, Hurri H, Pohjolainen T.

Mini-intervention for subacute low back pain: two-year follow-up and modifiers of effectiveness.

Spine. 2004;29(10):1069–1076Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Pohjolainen T, Hurri H, Mutanen P, Rissanen P, Pahkajarvi H.

Mini-intervention for subacute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial.

Spine. 2003;28(6):533–540Niemisto L, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Rissanen P, Lindgren K-A, Sarna S, Hurri H.

A Randomized Trial of Combined Manipulation, Stabilizing Exercises,

and Physician Consultation Compared to Physician Consultation Alone

for Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003 (Oct 1); 28 (19): 2185–2191Niemisto L, Rissanen P, Sarna S, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Lindgren K-A, Hurri H.

Cost-effectiveness of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and

physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for

chronic low back pain: a prospective randomized trial with 2-year follow-up.

Spine. 2005;30(10):1109–1115Loisel P, Lemaire J, Poitras S, Durand MJ, Champagne F, Stock S, Diallo B, Tremblay C.

Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of a disability prevention model

for back pain management: a six year follow up study.

Occup Environ Med. 2002;59(12):807–815Hlobil H, Uegaki K, Staal JB, de Bruyne MC, Smid T, van Mechelen W.

Substantial sick-leave costs savings due to a graded activity intervention

for workers with non-specific sub-acute low back pain.

Eur Spine J. 2007;16(7):919–924Molde Hagen E, Grasdal A, Eriksen HR.

Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave

for low back pain: a 3-year follow-up study.

Spine. 2003;28(20):2309–2315Skouen JS, Grasdal AL, Haldorsen EMH, Ursin H.

Relative cost-effectiveness of extensive and light multidisciplinary treatment programs

versus treatment as usual for patients with chronic low back pain

on long-term sick leave: randomized controlled study.

Spine. 2002;27(9):901–909Torstensen TA, Ljunggren AE, Meen HD, Odland E, Mowinckel P, Geijerstam S.

Efficiency and costs of medical exercise therapy, conventional physiotherapy, and self-exercise

in patients with chronic low back pain. A pragmatic, randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial

with 1-year follow-up.

Spine. 1998;23(23):2616–2624Kominski GF, Heslin KC, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, Harber PI.

Economic evaluation of four treatments for low-back pain: results from a randomized controlled trial.

Med Care. 2005;43(5):428–435Seferlis T, Lindholm L, Nemeth G.

Cost-minimisation analysis of three conservative treatment programmes in

180 patients sick-listed for acute low-back pain.

Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18(1):53–57Whitehurst DGT, Lewis M, Yao GL, Bryan S, Raftery JP, Mullis R, Hay EM.

A brief pain management program compared with physical therapy for low back pain:

results from an economic analysis alongside a randomized clinical trial.

Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):466–473Critchley DJ, Ratcliffe J, Noonan S, Jones RH, Hurley MV.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three types of physiotherapy used to reduce

chronic low back pain disability: a pragmatic randomized trial with economic evaluation.

Spine. 2007;32(14):1474–1481Hollinghurst S, Sharp D, Ballard K, Barnett J, Beattie A, Evans M, Lewith G, Middleton K, et. al.

Randomised controlled trial of alexander technique lessons, exercise, and

massage (ateam) for chronic and recurrent back pain: economic evaluation.

BMJ. 2008;337:a2656Johnson RE, Jones GT, Wiles NJ, Chaddock C, Potter RG, Roberts C, Symmons DPM, Watson PJ.

Active exercise, education, and cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent

disabling low back pain: a randomized controlled trial.

Spine. 2007;32(15):1578–1585Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, Castelnuovo E, Withers EJ, Nichols V, Potter R, Underwood MR.

Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care:

a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis.

Lancet. 2010;375(9718):916–923Ratcliffe J, Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Brazier J.

A randomised controlled trial of acupuncture care for persistent low back pain: cost effectiveness analysis.

BMJ. 2006;333(7569):626Rivero-Arias O, Gray A, Frost H, Lamb SE, Stewart-Brown S.

Cost-utility analysis of physiotherapy treatment compared with physiotherapy advice in low back pain.

Spine. 2006;31(12):1381–1387Rivero-Arias O, Campbell H, Gray A, Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J.

Surgical stabilisation of the spine compared with a programme of intensive rehabilitation for

the management of patients with chronic low back pain: cost utility analysis based on a randomised controlled trial.

BMJ. 2005;330(7502):1239UK BEAM Trial United kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial:

Cost Effectiveness of Physical Treatments for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 1381–1385Goossens ME, Rutten-Van Molken MP, Kole-Snijders AM, Vlaeyen JW, Van Breukelen G, Leidl R.

Health economic assessment of behavioural rehabilitation in chronic low back pain:

a randomised clinical trial.

Health Econ. 1998;7(1):39–51Smeets RJ, Severens JL, Beelen S, Vlaeyen JW, Knottnerus J.

More is not always better: cost-effectiveness analysis of combined, single behavioral and

single physical rehabilitation programs for chronic low back pain.

Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):71–81van der Roer N, van Tulder M, van Mechelen W, de Vet H.

Economic evaluation of an intensive group training protocol compared with usual

care physiotherapy in patients with chronic low back pain.

Spine. 2008;33(4):445–451Schweikert B, Jacobi E, Seitz R, Cziske R, Ehlert A, Knab J, Leidl R.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adding a cognitive behavioral treatment to

the rehabilitation of chronic low back pain.

J Rheumatol. 2006;33(12):2519–2526Witt CM, Jena S, Selim D, Brinkhaus B, Reinhold T, Wruck K, Liecker B, Linde K.

Pragmatic randomized trial evaluating the clinical and economic effectiveness

of acupuncture for chronic low back pain.

Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(5):487–496Herman PM, Szczurko O, Cooley K, Mills EJ.

Cost-effectiveness of naturopathic care for chronic low back pain.

Altern Ther Health Med. 2008;14(2):32–39Hilde G, Hagen KB, Jamtvedt G, Winnem M (2002)

Advice to stay active as a single treatment for low back pain and sciatica.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD003632Boulenger S, Nixon J, Drummond M, Ulmann P, Rice S, de Pouvourville G.

Can economic evaluations be made more transferable?

Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6(4):334–346Edejer TT.

Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 11.

Incorporating considerations of cost-effectiveness, affordability and resource implications.

Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4:23Goeree R, Burke N, O’Reilly D, Manca A, Blackhouse G, Tarride JE.

Transferability of economic evaluations: approaches and factors to consider when

using results from one geographic area for another.

Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):671–682Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A, McAuley JH.

Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study.

BMJ. 2008;337:a171Costa LdC, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Hancock MJ, Herbert RD, Refshauge KM, Henschke N.

Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study.

BMJ. 2009;339:b3829Jellema P, van der Roer N, van der Windt DAWM, van Tulder MW, van der Horst HE.

Low back pain in general practice: cost-effectiveness of a minimal psychosocial intervention versus usual care.

Eur Spine J. 2007;16(11):1812–1821

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Return to COST EFFECTIVENESS JOINT STATEMENT

Since 2-25-2011

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |