Association of Initial Provider Type

on Opioid Fills for Individuals With Neck PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Archives of Phys Med and Rehab 2020 (Aug); 101 (8): 1407–1413 ~ FULL TEXT

Christopher J. Louis, PhD, Carolina-Nicole S. Herrera, MA, Brigid M. Garrity, MS, MPH, Christine M. McDonough, PT, PhD, Howard Cabral, PhD, Robert B. Saper, MD, Lewis E. Kazis, ScD

Department of Health Law, Policy, and Management,

Boston University School of Public Health,

Boston, Massachusetts.

Objective: To determine whether the initial care provider for neck pain was associated with opioid use for individuals with neck pain.

Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Marketscan research databases.

Participants : Patients (N=427,966) with new-onset neck pain from 2010-2014.

Main outcome measures: Opioid use was defined using retail pharmacy fills. We performed logistic regression analysis to assess the association between initial provider and opioid use. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using bootstrapping logistic models. We performed propensity score matching as a robustness check on our findings.

Results: Compared to patients with neck pain who saw a primary health care provider, patients with neck pain who initially saw a conservative therapist were 72%–91% less likely to fill an opioid prescription in the first 30 days, and between 41%–87% less likely to continue filling prescriptions for 1 year. People with neck pain who initially saw emergency medicine physicians had the highest odds of opioid use during the first 30 days (OR, 3.58; 95% CI, 3.47–3.69; P<.001).

Conclusions: A patient's initial clinical contact for neck pain may be an important opportunity to influence subsequent opioid use. Understanding more about the roles that conservative therapists play in the treatment of neck pain may be key in unlocking new ways to lessen the burden of opioid use in the United States.

Keywords: Analgesics, opioid; Conservative therapy; Neck pain; Rehabilitation.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

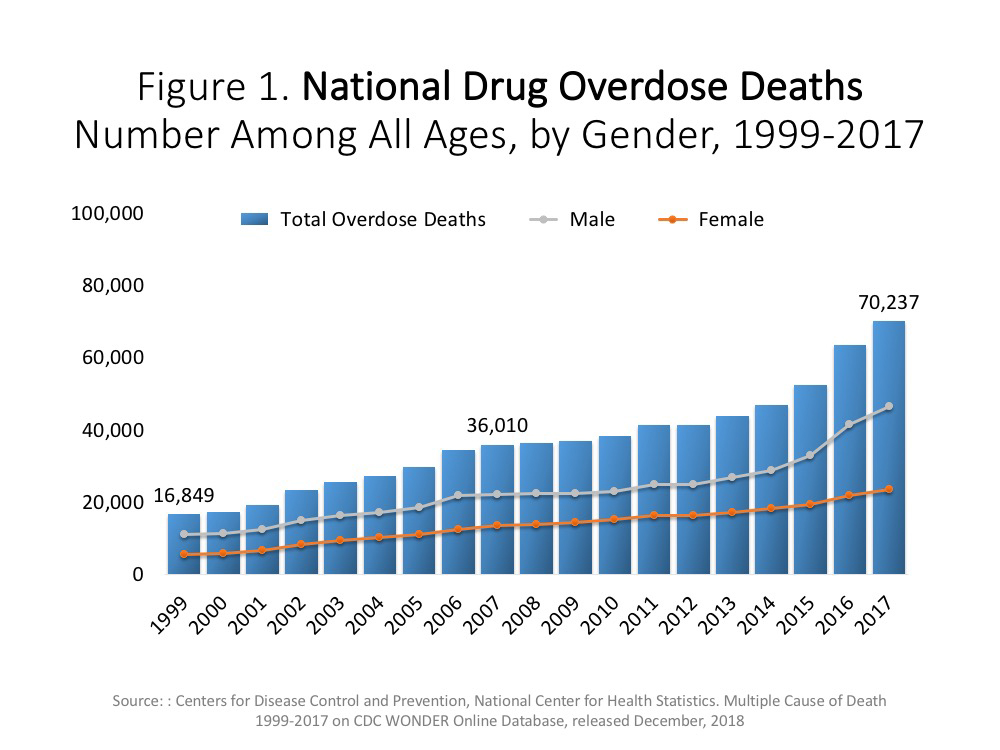

Neck pain affects approximately 1 in 3 adults each year1 and is among the leading causes of disability in the United States with annual expenditures of nearly $90 billion. [1–4] Studies have identified a concerning relationship between neck pain and opioid use and suggest that people with neck pain (PWNP) are more likely to use opioids than those with other musculoskeletal pain. [5, 6] Up to 29% of patients with chronic pain who are prescribed opioids misuse the opioids. [7] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [8] recently recommended nonpharmacologic approaches as first-line treatment for neck pain, yet opioids remain one of the most administered treatments for chronic pain. [9, 10]

The literature on musculoskeletal conditions indicates that initial provider type may be associated with lower risk of opioid use. [11, 12] One study found that PWNP who sought care from chiropractors and physical therapists had lower opioid exposure in the year following the start of care thanPWNPwho initially sought care from primary care physicians (PCPs), [13] whereas another suggested that early engagement with a physical therapist was associated with lower long-term opioid use. [14] These studies are limited by relatively small, nongeneralizable samples. A richer, more comprehensive study examining these relationships is warranted.

In the present study, we use longitudinal data from one of the largest national samples of people with commercial insurance and ask if initial provider type is associated with short- or long-term opioid use by PWNP.

Methods

Data source and cohort development

Using claims data from the Marketscana research databases (2009– 2016), we identified a sample of opioid-na?ve patients with a primary, outpatient neck pain diagnosis between 2010 and 2014 (fig 1). The Marketscan research databases contain fully adjudicated medical and prescription drug claims from large, selfinsured employers. These employers subcontract administration of their preferred provider organization (PPO), point of service plan, health maintenance organization (HMO), high-deductible health plan, consumer-driven health plan, and “comprehensive” plans (usually historically older PPO-style plans) to insurers. The names of these employers are not revealed, and the employer list changes from year to year. Prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014, some employers had behavioral health or prescription carve-out plans, which meant that the enrollee’s behavioral health claims and prescription claims were not reported. As we used index claims from before the implementation of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10, all the medical codes used in this study were ICD-9. Prescription drugs were identified using a national drug code.

Index claims

Using ICD-9 codes (supplemental appendix S1, supplemental table S1, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/), we identified and flagged all 2010–2014 outpatient claims that had at least 1 neck pain diagnosis. We sorted these claims by patient identifiers and then date of claim. We identified the earliest claim for each PWNP as that patient’s “index claim.” We then reviewed the medical, prescription drug, and insurance enrollment records of PWNP to determine whether the patient met inclusion criteria.

Eligibility

To be eligible for the study, PWNP were identified as adults (18–64y) who were continuously enrolled in commercial insurance 1 year before and 2 years after the index neck pain diagnosis. We excluded PWNP who had a traumatic injury or neck cancer [15]; who were enrolled for less than 12 months of insurance in any study year; who did not have prescription drug coverage; who had an opioid fill or a ben=odiazepine fill in the year prior to initial neck pain diagnosis; or had a medical claim with a neck pain diagnosis during the 365 days before the index neck pain diagnosis. We also required the PWNP to have full demographic data (table 1). Codes for inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in supplemental appendix S1 and supplemental table S1.

Independent variable

Our independent variable of interest was initial provider type. By initial provider, we mean the billing provider as identified by Marketscan who was associated with a PWNP’s first neck pain diagnosis (see supplemental appendix S1 and supplemental table S2, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/). We created 9 provider categories: conservative therapists (acupuncturist, chiropractor, or physical therapist), PCPs, and specialists (emergency medicine, orthopedic surgeon, neurologist, rehabilitation physician, or any other clinician). We excluded radiologists as initial providers, since imaging may require a referral from another provider. For 18% of initial neck pain diagnosis codes associated with a radiologist, we correlated that visit with a “nearest neighbor” claim that occurred within 14 days before the index claim or within 2 days after the index claim. If there were multiple providers on the index visit day or nearest neighbor day, we used a hierarchy to identify the billing provider (for order, see table 1). Any imaging claims for which a nearest neighbor could not be identified were classified as “other.”

Covariates

The covariates used in this study were PWNP demographics and health status. Demographics were drawn from the index year data provided in the Marketscan enrollment files. We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Elixhauser Comorbidity Index software,b version 3.7, to identify PWNP with medical, alcohol, drug use, and psychologic conditions in the year before the index visit. [16] PWNP were identified with an Elixhauser-specified condition if the software identified at least 1 inpatient visit with the condition or at least 2 outpatient visits with the condition. [17–19] We summed the 14 medical conditions into a continuous variable (0 meaning no medical conditions and 14 indicating the PWNP had all medical conditions) and retained the binary flags for the behavioral health disorders.

Dependent variables

Our outcome was opioid use, which was defined using retail pharmacy fills and operationalized as a binary indicator of opioid prescription claims during the first 30 days after an index visit (short term) and for 4 continuous quarters after the index visit (long term). [20–22] Using data from the Marketscan prescription claims, we identified PWNP who had opioid prescription fills during the 2 years after an initial provider visit. For most opioid claims, we applied the prescription date as the fill date. For refill claims with payment dates greater than 30 days after the prescription date, we used the payment date as the fill date. We identified short-term opioid use as a prescription filled within the first 30 days after an initial provider visit. [23] For completeness, we also examined outcomes at 0–3 days and 0–90 days and found the same patterns as at 30 days. We defined long-term opioid use as at least 1 opioid prescription fill per quarter for at least 1 year. [24]

Analyses

We used descriptive statistics, logistic regression analysis, and propensity score matching to assess the association between initial provider and opioid use. We hypothesized that personal characteristics, the initial provider type, and health status would influence short- and long-term opioid use.

The PWNP who received their first neck pain diagnosis from a PCP were the reference population for our regression analysis. We controlled for PWNP age, sex, insurance type (eg, PPO, HMO, etc), enrollee status (enrollee, enrollee partner, dependent), rural residency (ie, does not live in a metropolitan area), and health status. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using bootstrapped logistic models. [25] We used the same model in each regression. PCP was the reference group for all logistic regressions. We graphed each of the adjusted ORs to compare changes in odds of opioid use by initial provider and time period. Model discrimination (c statistic) and calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test) were estimated (supplemental appendix S2, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/). The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics were significant, but the differences between the observed and expected values within decile groups were relatively small, suggesting significance was likely due to the large sample size. [11, 12]

We performed sensitivity analyses using propensity score matching to further examine potential differences in PWNP characteristics and initial provider types (see table 1). We identified matched sets of non-PCP PWNP to PCP PWNP and performed robust logistic regression analysis on the matched samples. [26] The details of this propensity score analysis appear in supplemental appendix S3 (available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/).

This study was approved by the Boston University Medical Campus institutional review board and deemed as nonhuman studies research given that all data was de-identified. All analyses were performed with Statac software, version 14.2.

Results

A total 427,966 individuals met all inclusion criteria and had a new-onset, neck pain diagnosis during the study period (see fig 1). Table 1 indicates that over 40% of the study sample saw a chiropractor for their initial neck pain visit (n=178,705), with the next most frequent initial provider being a PCP (n=121,817). PWNP who saw PCPs were significantly younger than the PWNP who saw clinician specialists (see supplemental appendix S2, supplemental table S3). Table 1 reports the share of patients by clinician type and insurance. Most PWNP seeking initial treatment had PPO insurance (ranging from 58.8%–70.4%) with the next most frequent plans being HMOs (ranging from 6.7%–18.4%) and high-deductible health plans (ranging from 7.1%–9.7%). Most individuals were the primary enrollee in their insurance plan, whereas 23.3%–25.0% were listed as partners and 3.2%–14.5% were dependents. PWNP who saw a neurologist first had the highest score for physical comorbidities (0.68), whereas PWNP who saw a chiropractor first had the lowest medical comorbidity score (0.08). PWNP who saw conservative therapists had significantly fewer medical comorbidities compared to PWNP who saw other providers (see supplemental appendix S2, supplemental table S3).

Approximately 8% of PWNP had an opioid prescription filled within 3 days of their diagnosis, representing 49% of all PWNP who had an opioid fill (table 2). About 11.6% had an opioid prescription within the first 30 days. PWNP who first saw an acupuncturist (1.7%), chiropractor (2.9%), or physical therapist (5.3%) had an opioid fill in the first 30 days after an initial visit compared to PWNP who initially saw an orthopedic surgeon (11.3%), PCP (12.9%), or emergency medicine physician (36.5%). About 1% of PWNP had at least 1 opioid prescription fill per quarter for a year after the initial visit. Less than 1% of PWNP who initially saw a conservative therapist had at least 1 opioid prescription filled each quarter for a year after the initial visit. By contrast, 2.7% of PWNP whose initial provider was an orthopedic surgeon or neurologist had ongoing opioid prescriptions for at least 1 year after the initial visit.

After controlling for demographics and comorbidities, we found that PWNP who initially saw a conservative therapist for neck pain had significantly lower odds of short- and long-term opioid use, as compared to PWNP who initially saw a PCP (fig 2; supplemental appendix S2, supplemental tables S3 and S4). PWNP who initially saw an acupuncturist had the lowest odds of an opioid fill within 30 days (OR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.07–0.11; P<.001) and 1 year (OR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.06–0.25; P<.001]). PWNP who initially saw a chiropractor had the next lowest odds at 30 days (OR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.14–0.15; P<.001]) and 1 year (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.14–0.18; P<.001]). PWNP who initially saw physical therapists had the third lowest odds at 0–30 days (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.25–0.30; P<.001) and at 1 year (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.48–0.72; P<.001).

PWNP who initially saw emergency medicine physicians had the highest odds of opioid fill at all time points up to the first 30 days (OR, 3.58; 95% CI, 3.47–3.69; P<.001) and did not differ significantly at 1 year from PWNP who saw a PCP first. PWNP who saw rehabilitation physicians (OR, 0.71 at 0–30 days; 95% CI, 0.66–0.76; P<.001) and neurologists (OR, 0.63 at 0–30 days; 95% CI, 0.59–0.67; P<.001) initially had significantly lower odds of short-term opioid use than PWNP who saw PCPs first. However, at 1 year after the index visit, PWNP who initially saw orthopedic surgeons (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.59–1.99; P<.001), rehabilitation physicians (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.15–1.74; P<.001]) and neurologists (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.42–1.93; P<.001]) had significantly higher odds of opioid use than PWNP who saw PCPs first.

We confirmed these findings with a propensity matching analysis (supplemental appendix S2, supplemental table S4, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/). Nearly all propensity matched ORs of short- and long-term opioid use by initial provider were consistent with our logistic models. Two results were inconsistent between the logistic and matching analysis: the findings on the odds of an opioid fill in the first 30 days by PWNP who initially saw orthopedic surgeons and opioid use in the 0–90 day period by other physician specialists. Other responses for these groups were consistent with the logistic regressions. These findings may reflect confounding associated with the patient’s physical comorbidities, initial severity of injury for PWNP who were diagnosed by orthopedic surgeons, or confounding arising from conditions for PWNPs initially diagnosed by clinicians who were not typically consulted for neck pain. As a result, we cannot conclusively say whether there was a significant association between opioid use and orthopedic surgeons, or other physician specialists for those respective time periods.

Discussion

We examined whether the initial provider for new-onset neck pain was associated with opioid use in the year following diagnosis. We found that more than 49% of PWNP who used opioids during the study period used opioids within 3 days of their diagnosis. Further, we also found that PWNP who received their initial diagnosis from conservative therapists had lower odds of short- and longterm opioid use compared to PNWP who were initially diagnosed by PCPs. Conversely, PWNP who received their initial neck pain diagnosis from emergency medicine physicians were about 300% more likely to have an opioid prescription filled in the month following the visit compared to PWNP initially diagnosed by PCPs. PWNP with an initial diagnosis from an orthopedic surgeon or neurologist were 115% and 199% more likely, respectively, to have ongoing opioid prescription fills up to a year after the initial visit than PNWP initially diagnosed by PCPs. Our findings suggest that the diagnosing provider is significantly associated with subsequent opioid use. We found a strong relationship between seeing a conservative therapist for an initial neck pain diagnosis and significantly lower odds of using opioids within a year of that diagnosis. While these findings are associative, our results advance the evidence on the relationship between initial provider and opioid use for neck pain. Previous studies of initial provider type have had a limited focus on a single health plan or state or the use of small samples with particular diagnoses such as cervical fusions. [13, 14] We address these limitations by studying a national sample across several years and examining a diverse group of clinicians. Our findings are consistent across the different types of conservative therapists. Understanding the role that conservative therapists play in neck pain treatment may unlock new ways to lessen the burden of opioid use in the United States.

Another important finding from this study is the association between emergency physician visits and higher short-term opioid use. Earlier reports suggest that emergency physicians were more likely to prescribe opioids for neck and back pain than other providers. [27–29] While a prior study found that implementation of emergency department prescribing guidelines led to an immediate 22% reduction in opioid prescriptions for PWNP, [29] we confirmed that PWNP who received their initial diagnosis from an emergency department physician were significantly more likely to have an opioid fill within 90 days of their visit compared to other PWNPs. Emergency department leaders concerned with shortterm opioid prescribing may wish to consider developing policies to help clinicians determine when patients might benefit from alternatives to opioids. Health care leaders should support interventions to help PWNPs who sought emergency care to access appropriate follow-up care.

Of additional concern was the association between seeing neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons for an initial diagnosis and long-term opioid use by PWNP. Of the patients who had opioid prescriptions in every quarter of the year following their initial neck pain diagnosis, over 13.5% were seen by these 2 specialties, despite the patients of these 2 specialties only comprising 5.5% of the sample. After controlling for comorbidities and matching, the association of long-term opioid use with diagnosis by these providers remained strong. The management of PWNP who are initially diagnosed by orthopedic surgeons and neurologists should be further investigated to better understand the role of opioids in their treatment and recovery.

Finally, although there is interest in determining causal relationships linking provider types and opioid use, this is an observational study design that draws conclusions in terms of associations and not causation. Nonetheless, the relationships identified in this study provide an evidence base that can be used in future studies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The use of claims data limited our ability to eliminate the influence of confounders such as severity and duration of pain. Measurements of severity are generally unavailable in claims data and rarely available in electronic medical records data. However, we were able to control for comorbidities, including use of the Elixhauser Index, as a proxy for complexity that has been used in other studies. Second, we did not have information about what type of providers patients had access to and their decision-making around provider choice. PWNP selecting a conservative therapist for an initial diagnosis may have a predilection for not taking opioids. Additionally, conservative therapists may counsel PWNP to not take pain medications. To control for confounders, our analysis included propensity matched methods and confirmed our findings for conservative therapists. [30] Third, this study focused on commercially-insured adults with neck pain, so these findings may not be generalizable beyond this population. About 55% of the adult American population was commercially-insured between 2010 and 2014 and our results have important implications for this group. [31] Fourth, we did not evaluate whether subsequent therapies or ongoing care were associated with opioid use. The data did not allow us to investigate whether patients received “new” opioid prescriptions after completing neck pain treatment. Given the numerous types of specialists a PWNP can choose to see, further research is needed to determine whether different combinations of providers may have a significant effect on opioid use.

Conclusions

Our study found that the type of initial provider for neck pain was associated with subsequent opioid use. The initial clinical contact for a patient seeking care for neck pain may be an important opportunity to influence subsequent opioid use. Clinician leaders concerned with short-term opioid prescribing may wish to consider developing policies to help emergency department clinicians and specialists determine when patients might benefit from alternatives to opioids. Understanding more about the roles that conservative therapists could play in the treatment of patients with neck pain may help decrease the risk of opioid dependency.

References:

Cohen SP.

Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of neck pain.

Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:284-99.Murray CJL, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, Birbeck G, Burstein R, Chou D, et al.

The State of US Health, 1990-2010:

Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors

JAMA 2013 (Aug 14); 310 (6): 591–608Dieleman JL, Baral R, Birger M, et al.

US Spending on Personal Health Care and Public Health, 1996-2013

JAMA 2016 (Dec 27); 316 (24): 2627-2646Davis MA, Onega T, Weeks WB, Lurie JD.

Where the United States Spends its Spine Dollars:

Expenditures on Different Ambulatory Services

for the Management of Back and Neck Conditions

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (Sep 1); 37 (19): 1693–1701Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Long CR, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM.

Association among opioid use, treatment preferences, and perceptions

of physician treatment recommendations in patients with neck and back pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2018;41:175-80.Fischbein R, Mccormick K, Selius BA, et al.

The assessment and treatment of back and neck pain: an initial investigation

in a primary care practice-based research network.

Prim Health Care Res Dev 2014;16:461-9.Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN.

Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis.

Pain 2015;156:569-76.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain:

United States, 2016

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Recommendations and Reports Vol. 65 No. 1 March 18, 2016Qaseem, A, Wilt, TJ, McLean, RM, and Forciea, MA.

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Opioid overdose drug overdose deaths. Available at:

https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html

Accessed February 15, 2019.Fritz JM, Kim J, Dorius J.

Importance of the Type of Provider Seen to Begin Health Care

for a New Episode Low Back Pain: Associations

with Future Utilization and Costs

J Eval Clin Pract. 2016 (Apr); 22 (2): 247–252Frogner BK, Harwood K, Andrilla CH, Schwartz M, Pines JM.

Physical therapy as the first point of care to treat low back pain: an instrumental variables approach

to estimate impact on opioid prescription, health care utilization, and costs.

Health Serv Res 2018;53:4629-46.Horn ME, George SZ, Fritz JM.

Influence of Initial Provider on Health Care Utilization

in Patients Seeking Care for Neck Pain

Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017 (Oct 19); 1 (3): 226–233Sun E, Moshfegh J, Rishel CA, Cook CE, Goode AP, George SZ.

Association of early physical therapy with long-term opioid use among opioid-naive patients

with musculoskeletal pain.

JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e185909.Feudtner C, Hexem KR, Shabbout M, Feinstein JA, Sochalski J, Silber JH.

Prediction of pediatric death in the year after hospitalization: a population-level

retrospective cohort study.

J Palliat Med 2009; 12:160-9.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM.

Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data.

Med Care 1998;36:8-27.Ensrud KE, Lui LY, Langsetmo L, et al.

Effects of mobility and multimorbidity on inpatient and postacute

health care utilization.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;73:1343-9.Chu YT, Ng YY, Wu SC.

Comparison of different comorbidity measures for use with administrative data

in predicting short- and longterm mortality.

BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:140.Baldwin LM, Klabunde CN, Green P, Barlow W, Wright G.

In search of the perfect comorbidity measure for use with administrative claims data.

Med Care 2006;44:745-53.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J.

A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics.

J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:323-37.McKenizie DA.

The validity of Medicaid pharmacy claims for estimating drug use among elderly

nursing home residents: the Oregon experience.

J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:1248-57.Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al.

Observational Retrospective Study of the Association of Initial

Healthcare Provider for New-onset Low Back Pain with

Early and Long-term Opioid Use

BMJ Open. 2019 (Sep 20); 9 (9): e028633Korff MV, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R.

Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered.

Ann Intern Med 2011;155:325-8.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al.

The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain:

a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health pathways to prevention workshop.

Ann Intern Med 2015;162:276-86.SAS Support.

Jackknife and bootstrap analyses. Available at:

http://support.sas.com/kb/24/982.html

Accessed November 6, 2018.Louis CJ, Clark JR, Hillemeier MM, Camacho F, Yao N, Anderson RT.

The effects of hospital characteristics on delays in breast cancer diagnosis

in Appalachian communities: a populationbased study.

J Rural Health 2017;34:s91-103.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB.

Opioid prescribing by emergency physicians and risk of long-term use.

N Engl J Med 2017;376:1895-6.Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, et al.

Opioid prescribing in a cross section of US emergency departments.

Ann Emerg Med 2015;66: 253-9.Portal DA, Healy ME, Satz WA, Mcnamara RM.

Impact of an opioid prescribing guideline in the acute care setting.

J Emerg Med 2016;50: 21-7.Austin PC.

An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects

of confounding in observational studies.

Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399-424.Kaiser Family Foundation.

Health insurance coverage of the total population. Available at:

www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/totalpopulation/?currentTimeframeZ4&sortModelZ{"colId":"Location", "sort":"asc"}

Accessed December 19, 2019.

Return to OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 6-21-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |