Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of

Prescription Opioids in Patients with Spinal PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain Medicine 2020 (Dec 25); 21 (12): 3567–3573 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS James M. Whedon, DC, MS, Andrew W. J. Toler, MS, Louis A. Kazal, MD, Serena Bezdjian, PhD, Justin M. Goehl, DC, MS, and Jay Greenstein, DC

Southern California University of Health Sciences,

Whittier, California.

OBJECTIVE: Utilization of nonpharmacological pain management may prevent unnecessary use of opioids. Our objective was to evaluate the impact of chiropractic utilization upon use of prescription opioids among patients with spinal pain.

DESIGN AND SETTING: We employed a retrospective cohort design for analysis of health claims data from three contiguous states for the years 2012-2017.

SUBJECTS: We included adults aged 18-84 years enrolled in a health plan and with office visits to a primary care physician or chiropractor for spinal pain. We identified two cohorts of subjects: Recipients received both primary care and chiropractic care, and nonrecipients received primary care but not chiropractic care.

METHODS: We performed adjusted time-to-event analyses to compare recipients and nonrecipients with regard to the risk of filling an opioid prescription. We stratified the recipient populations as: acute (first chiropractic encounter within 30 days of diagnosis) and nonacute (all other patients).

RESULTS: The total number of subjects was 101,221. Overall, between 1.55 and 2.03 times more nonrecipients filled an opioid prescription, as compared with recipients (in Connecticut: hazard ratio [HR] = 1.55, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.11-2.17, P = 0.010; in New Hampshire: HR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.92-2.14, P < 0.0001). Similar differences were observed for the acute groups.

CONCLUSIONS: Patients with spinal pain who saw a chiropractor had half the risk of filling an opioid prescription. Among those who saw a chiropractor within 30 days of diagnosis, the reduction in risk was greater as compared with those with their first visit after the acute phase.

KEYWORDS: Spine Pain; Back pain; Neck Pain; Chiropractic; Analgesics; Opioid

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Opioid Prescription Crisis

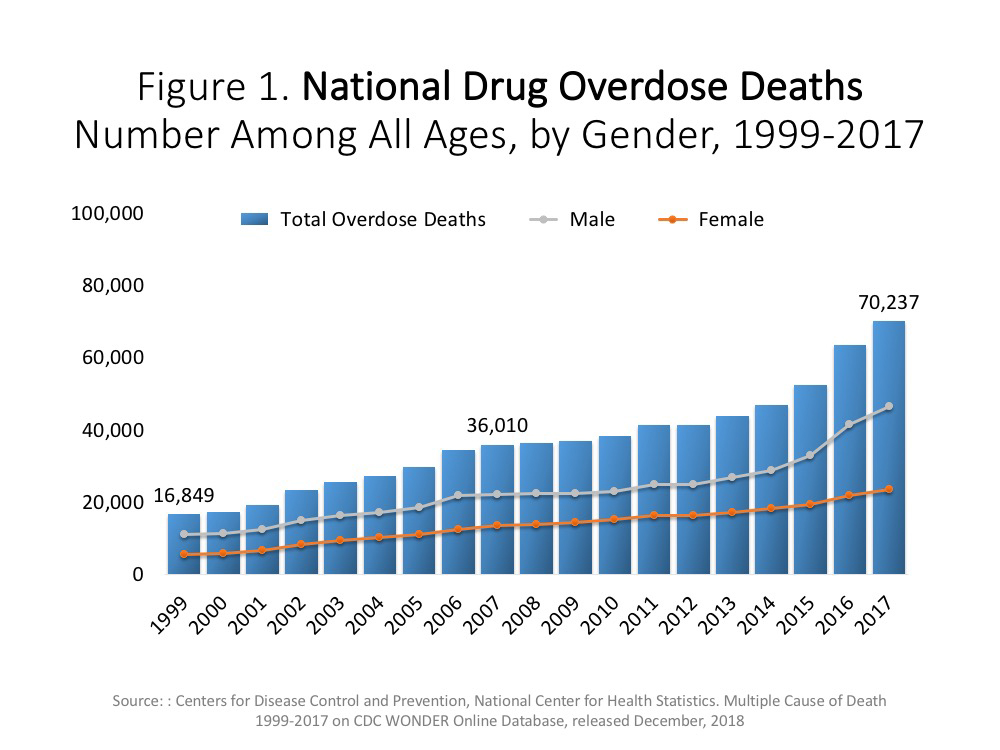

The risks associated with the use of prescription opioid analgesics are well known. Drug overdose deaths in 2017 increased by almost 10% over 2016, with opioids accounting for almost 48,000 cases. [1] Promising improvement has been made in curtailing excessive and inappropriate prescribing practices and in the acute treatment of opioid use disorder. [1] However, to prevent unnecessary use of opioids, there is a pressing need to identify safe and cost-effective alternatives for the treatment of pain. Increasing attention is being paid to the potential of nonpharmacological pain treatment as an upstream strategy for addressing the opioid epidemic.

Chiropractic: A Nonpharmacological Alternative to Opioids

The Institute of Medicine has recommended the use of nonpharmacological therapies as effective alternatives to pharmacotherapy for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. [2] Among US adults prescribed opioids, 59% reported having back pain. [3] Recently published clinical guidelines from the American College of Physicians recommend nonpharmacological treatment as the firstline approach to treating back pain, with consideration of opioids only as the last treatment option or if other options present substantial risk to the patient. [4] In general, it is not known if the use of nonpharmacological therapies for musculoskeletal pain influences opioid use [5], but in that regard there is some emerging evidence in favor of chiropractic care.

Doctors of Chiropractic (DCs) provide nonpharmacologic treatment for spinal pain, using a multimodal functional approach that typically includes spinal manipulation and exercise, in accordance with international clinical practice guidelines. [6] A recent study of the implementation of a conservative spine care pathway reported that among patients treated for spinal pain, as expenditures for manual care (chiropractic and physical therapy) increased, expenditures for opioid therapy decreased, as did costs for spinal surgery and spine care overall. [7]

A retrospective claims study of 165,569 adults diagnosed with low back pain found that utilization of services delivered by DCs was associated with reduced use of opioids. [8] The supply of DCs, as well as spending on spinal manipulative therapy, is inversely correlated with opioid prescriptions in disabled Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 [9]. In a cohort of 1,702 patients with a new episode of neck pain, those who received DC care had decreased odds of being prescribed opioids within one year of their first visit (odds ratio [OR] = 0.54, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.39–0.76). [10] In a 2018 report of a study conducted among 14,025 veterans of recent wars, the percentage of patients receiving opioid prescriptions was lower after receiving DC care for low back pain as compared with before. [11] Also, in 2018, a study of health insurance claims for the treatment of low back pain in New Hampshire found a 55% reduction in the likelihood of opioid prescription fill among recipients of chiropractic care as opposed to nonrecipients. [12]

In 2019, Kazis et al. [13] reported that patients who were initially treated by a chiropractor, acupuncturist, or physical therapist had decreased odds of both short- and long-term opioid use as compared with initial treatment by a primary care physician. Also in 2019, a systematic review of six studies examining the association between chiropractic use and opioid use found that opioid prescriptions were significantly lower among chiropractic users as compared with nonusers. [14]

Reduced use of opioids among recipients of chiropractic services may in turn lead to lower costs and improved safety. The objective of this investigation was to build upon our research in New Hampshire with a larger study population, a longer time frame, and more advanced methods, evaluating data from three New England states for the impact of chiropractic utilization upon use of prescription opioids among patients with spinal pain.

Methods

Overview

We hypothesized that among patients diagnosed with spinal pain, recipients of chiropractic services have a lower risk of filling a prescription for an opioid analgesic as compared with nonrecipients. To test this hypothesis, we employed a retrospective cohort design to analyze health insurance claims data. Our data sources were the All Payer Claims Databases (APCDs) of the three contiguous states of Connecticut (CT), Massachusetts (MA), and New Hampshire (NH), which aggregate health claims data from third-party payers. This project was conducted subject to the terms of data user agreements between the principal investigator and the states. In accordance with standard rules for analysis of health claims, cells with N<11 were suppressed to prevent against disclosure of protected health information. The research methods were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the investigator’s university. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Study Population and Cohorts

Data extracted from the three APCDs were not merged together, but analyzed separately, in accordance with the terms of the data use agreements. We accessed health claims data for the years 2012–2017. We only included claims with payment amounts greater than zero. The study population was comprised of adults aged 18–84 years, enrolled in a health plan, and with office visits to a primary care physician and/or DC. We included only patients with continuous pharmacy coverage and at least two visits associated with a primary diagnosis of a spinal pain disorder between seven and 90 days apart. Thus, the study population included subjects with multiple office visits for spinal pain. Patients diagnosed with cancer at any time during the study period were excluded.

Among those included in the study population as defined above, we identified two cohorts of subjects:1) Recipients of chiropractic services (recipients) received both primary care and chiropractic care at any point in the study period.

2) Nonrecipients received primary care but did not receive chiropractic care at any time during the study period.For each subject, the first date associated with diagnosis of a spinal pain disorder was designated as the index date. We excluded all subjects with an opioid prescription fill that occurred before the index date. We accounted for immortal time bias by using first chiropractic visit only as a cohort inclusion criterion. Patients with an opioid prescription after their index date but before their first chiropractic visit remained in the analysis. We stratified the recipient population into two groups: 1) acute—patients whose first chiropractic encounter occurred within 30 days of the index date, and 2) nonacute — all other patients.

Outcomes Measurement

Following establishment of the cohorts, we modeled for likelihood of opioid prescription fill for up to six years of follow-up time. We controlled for patient demographics and health status at baseline through Charlson comorbidity scoring. Comorbidity scores were calculated from diagnoses documented during the one-year period preceding the index date. We performed adjusted timeto- event analyses, generating hazard ratios and Kaplan- Meier graphs to compare recipients and nonrecipients with regard to the risk of filling an opioid prescription subsequent to being diagnosed with a spinal pain disorder. To assess the effect of receiving chiropractic care early in an episode of care, we subanalyzed for risk of prescription fill in the acute and nonacute groups.

Results

Subject Characteristics

Subject characteristics may be viewed in Table 1. Total subjects, including both recipients and nonrecipients from all three states, numbered 101,221. The population was skewed toward younger age categories among subjects in NH and nonrecipients in MA. The skewed distribution was expected because Medicare claims were not included in the data sets. Recipients dominated the population in NH, whereas the opposite was true among subjects in MA. The number of subjects extracted from the CT database was low, considering the size of the state population (see the Discussion section for an explanation of the small population size for CT). Charlson comorbidity scores were higher among recipients in MA and nonrecipients in NH.

Time-to-Event Analysis

Results for the time-to-event analysis are displayed in Table 2. Overall, in the three states at any particular time in the study period, between 1.55 and 2.03 times more nonrecipients filled an opioid prescription, as compared with recipients (in Connecticut: hazard ratio [HR] = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.11–2.17, P = 0.010; in New Hampshire: HR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.92–2.14, P<0.0001). In other words, chiropractic recipients are at about half the risk of seeking an opioid over the sixyear follow-up period.

Significant differences were also observed for the acute group in all three states and for the nonacute group in NH. For the nonacute group in MA, no difference was observed between recipients and nonrecipients (HR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.71–1.26, P=0.71). For the nonacute group in CT, low numbers required data suppression and precluded statistical analysis. In both MA and NH, the protective effect against risk of prescription fill was higher for the acute group as compared with the nonacute group (in MA: HR = 1.68 acute vs HR = 0.95 nonacute; in NH: HR = 1.92 acute vs HR = 1.29 nonacute) (Table 2).

The Kaplan-Meier charts in Figures 1–3 illustrate the results of the time-to-event analysis. All six charts show a consistent reduction in risk over time for filling a prescription for opioids. The charts for CT illustrate the stepwise pattern commonly seen in survival analyses with smaller numbers of subjects. Also reflecting the relatively low sample size in CT, the two curves are closer together and P values are higher. The charts for MA and NH, which are based in analyses of larger study populations, show smoother time-to-event curves, greater separation between cohorts, and more narrow confidence intervals. For all three states, differences in risk for the acute group as compared with the overall analysis were negligible.

Discussion

A previously published analysis of NH data on patients with low back pain represented a snapshot in time of the risk of taking prescription opioids after chiropractic or nonchiropractic treatment. [12] The time-to-event analysis described here yields a more accurate depiction of comparative risk over time: It portrays the temporal relationships between the spine disorder index event and the first opioid fill for two modes of treatment.

The Kaplan-Meier graphs (Figures 1–3) show a remarkably consistent pattern over six years of follow-up for three US states, illustrating a strong protective effect of chiropractic care against risk of opioid prescription fill. The effect was stronger for patients who saw a chiropractor within the first 30 days of diagnosis of a spinal pain disorder, as compared with those who first saw a chiropractor in later, nonacute phases. Additionally, the protective effect of chiropractic care was sustained beyond 1,200 days after the index date in Massachusetts and beyond 1,500 days in the other states, indicating that once chiropractic treatment has been engaged in the acute phase, patients experience a lasting benefit that is measurable in years.

The pattern of repetitive encounters typical of a course of chiropractic care may account for the sustained benefit. The most recent chronic low back pain guidelines suggest two to three patient encounters per week for two to four weeks as a trial of chiropractic care. [15] Multiple opportunities for patient–doctor interaction may allow the chiropractor to review clinical progress, advise on home exercise, ergonomics, and other selfmanagement strategies, and provide reassurance, all of which may help improve outcomes and reduce the need for medication.

These findings echo previous reports of superior outcomes associated with early chiropractic intervention. [7, 16, 17] Although the case mix, subject age, sex, and comorbidity scores varied among the three states, the adjusted negative correlation between chiropractic care and opioid therapy remained strong across all models. It may prove instructive in future research to examine differences in medication use among patients who selfrefer for chiropractic care compared with those who are referred by a medical physician.

Heyward et al. [18] recently reported inconsistent coverage for nonpharmacologic therapies for spine pain and little integration in coverage between drug and nondrug approaches. More consistent is the accumulating evidence for increased utilization of chiropractic services as an upstream strategy for reducing dependence upon prescription opioid medications. In the context of the opioid crisis, the imperative for patient protection mandates aggressive pursuit of all promising strategies, including the elimination of barriers to access chiropractic services, and benefits designs intended to encourage early utilization of chiropractic services.

This study was subject to certain limitations. Across the three APCDs, we encountered variation in case mix that is reflected in differences by state in the proportion of recipients and nonrecipients. The variation may be attributable to population differences in health care utilization and insurance coverage or to differences by state administration in data collection, reporting, and release. Because the CT data set did not include provider specialty codes, we cross-walked national provider identifiers (NPIs) to taxonomy codes and cross-referenced those codes to provider specialty codes. This linkage resulted in significant data loss that is reflected in much smaller cohort sizes for CT.

In designing this study, we identified four main possible sources of bias. First, among recipients, there was potential for misclassification of the time-to-event analysis through immortal time bias. We eliminated this possibility by identifying recipients independently of the timing of their opioid prescriptions. Thus the time interval between index date and opioid fill was similar for all subjects, and measurement of time to event was consistent across cohorts. Second, due to the observational study design, there was potential for confounding by indication, whereby patients with more severe pain may have been more likely to use opioid medication. Diagnoses in claims data are unreliable indicators of pain severity.

We took steps to account for confounding by indication by excluding cancer patients and by adjusting for Charlson comorbidity score. Additionally, this study was subject to chronological bias, which was apparent in the acute vs nonacute subgroup analysis. Subjects in the nonacute groups were fewer in number, and the effect sizes were smaller. These differences may be attributable to differences in patient behavior or insurance benefits. Finally, the study may be subject to selection bias if recipients differed from nonrecipients by unmeasured characteristics. Despite these potential sources of bias and confounding, however, the results were remarkably similar across all three states.

Conclusions

Among patients with spinal pain disorders, for recipients of chiropractic care, the risk of filling a prescription for an opioid analgesic over a six-year period was reduced by half, as compared with nonrecipients. Among those who saw a chiropractor within 30 days of being diagnosed with a spinal pain disorder, the reduction in risk was greater as compared with those who visited a chiropractor after the acute phase had passed.

Acknowledgments

Data for this research were supplied by the Center for Health Information and Analysis (Boston, MA, USA), the Connecticut Health Insurance Exchange, the New Hampshire Insurance Department, and the NH Department of Health and Human Services.

References:

US Department of Health and Human Services.

Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids

Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General,

US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.Institute of Medicine (IOM)

Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention,

Care, Education, and Research

Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP, Sullivan MD.

Epidemiology of regular prescribed opioid use: Results from a national, population-based survey.

J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36(3):280–8.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530The Role of Nonpharmacological Approaches to Pain Management:

Proceedings of a Workshop

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

The National Academies Press, Washington, DC (2019)Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, Ferreira PH, Fritz JM.

Prevention and Treatment of Low Back Pain: Evidence, Challenges, and Promising Directions

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2368–2383Weeks WB, Pike J, Donath J, Fiacco P, Justice BD.

Conservative Spine Care Pathway Implementation is Associated with Reduced

Health Care Expenditures in a Controlled, Before-After Observational Study

J General Internal Medicine 2019 (Aug); 34 (8): 1381–1382Rhee Y, Taitel MS, Walker DR, Lau DT.

Narcotic drug use among patients with lower back pain in employer health plans:

A retrospective analysis of risk factors and health care services.

Clin Ther 2007;29(Suppl):2603–12.Weeks WB, Goertz CM.

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Per Capita Supply of Doctors of Chiropractic and Opioid Use

in Younger Medicare Beneficiaries

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016 (May); 39 (4): 263–266Horn ME, George SZ, Fritz JM.

Influence of Initial Provider on Health Care Utilization in Patients Seeking Care for Neck Pain

Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017 (Oct 19); 1 (3): 226–233Lisi AJ, Corcoran KL, DeRycke EC, et al.

Opioid Use Among Veterans of Recent Wars Receiving

Veterans Affairs Chiropractic Care

Pain Med. 2018 (Sep 1); 19 (suppl_1): S54–S60Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Goehl JM, Kazal LA.

Association Between Utilization of Chiropractic Services for Treatment of Low-Back Pain

and Use of Prescription Opioids

J Altern Complement Med. 2018 (Jun); 24 (6): 552–556Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al.

Observational Retrospective Study of the Association of Initial Healthcare Provider for New-onset

Low Back Pain with Early and Long-term Opioid Use

BMJ Open. 2019 (Sep 20); 9 (9): e028633Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, Steffens C, Brackett A, Lisi AJ.

Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt Among Patients with Spinal Pain:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Pain Medicine 2020 (Feb 1); 21 (2): e139–e145Globe, G, Farabaugh, RJ, Hawk, C et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Paskowski I, Schneider M, Stevens J, Ventura JM, Justice BD.

A Hospital-Based Standardized Spine Care Pathway: Report of a Multidisciplinary, Evidence-Based Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2011 (Feb); 34 (2): 98–106Keeney BJ, Fulton-Kehoe D, Turner JA, et al.

Early predictors of lumbar spine surgery after occupational back injury:

Results from a prospective study of workers in Washington State.

Spine 2013;38(11):953–64.Heyward J , Jones CM , Compton WM , et al .

Coverage of Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Low Back Pain Among US Public and Private Insurer

JAMA Network Open 2018 (Oct 5); 1 (6): e183044

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 3-07-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |