Chiropractors' Characteristics Associated with Their Number

of Workers' Compensation PatientsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Can Chiropr Assoc 2015 (Sep); 59 (3): 202–215 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Marc-André Blanchette, DC, MSc, J. David Cassidy, PhD, DrMedSc, Michèle Rivard, ScD, and Clermont E. Dionne, PhD

Public Health PhD Program,

School of Public Health,

University of Montreal,

Montreal, QC, Canada.

FROM: Texas Workers' Compensation ReportObjective: The purpose of this study was to identify characteristics of Canadian doctors of chiropractic (DCs) associated with their number of workers' compensation patients.

Summary of background data: It has been previously hypothesized that DCs that treat a relatively high volume of workers' compensation cases may have different characteristics than the general chiropractic community.

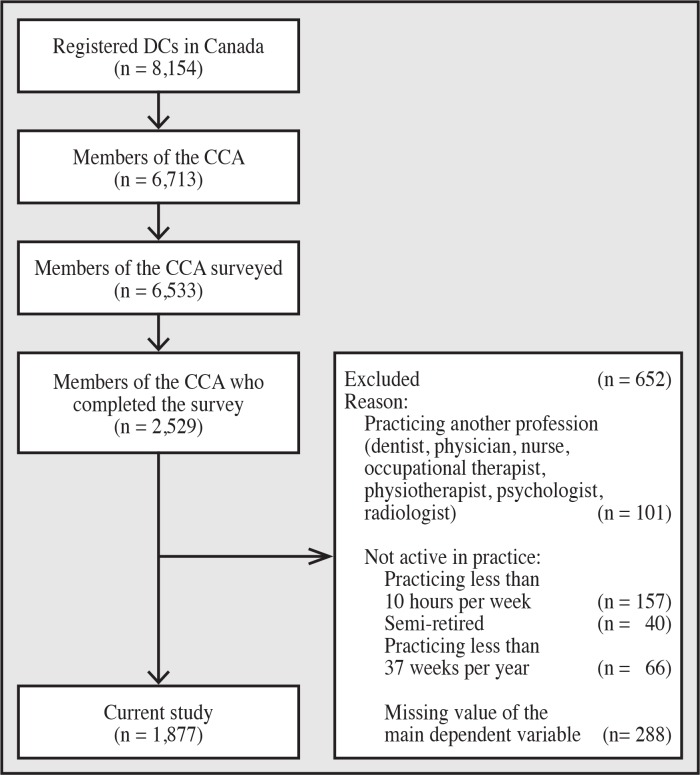

Methods: Secondary data analyses were performed on data collected in the 2011 survey of the Canadian Chiropractic Resources Databank (CCRD). The CCRD survey included 81 questions concerning the practice and concerns of DCs. Of the 6,533 mailed questionnaires, 2,529 (38.7%) were returned. Of these, 652 respondents did not meet our inclusion criteria, and our final study sample included 1,877 respondents. Bivariate analyses were conducted between predetermined independent variables and the annual number of workers' compensation patients. A negative binomial multivariate regression was performed to identify significant factors associated with the number of workers' compensation patients.

Results: On average, DCs received 10.3 (standard deviation (SD) = 17.6) workers' compensation cases and nearly one-third did not receive any such cases. The type of clinic (other than sole provider), practice area population (smaller than 500,000), practice province (other than Quebec), number of practice hours per week, number of treatments per week, main sector of activity (occupational/ industrial), care provided to patients (electrotherapy, soft-tissue therapy), percentage of patients with neuromusculoskeletal conditions, and percentage of patients referred by their employer or a physician were associated with a higher annual number of workers' compensation cases.

Conclusion: Canadian DCs who reported a higher volume of workers' compensation patients had practices oriented towards the treatment of injured workers, collaborated with other health care providers, and facilitated workers' access to care.

There are more articles like this @ our:

WORKERS' COMPENSATION PageKeywords: Workers’ Compensation Board; care seeking; chiropractic; occupational; survey; work related.

From the FULL TEXT Article

Introduction

“Work disability occurs when a worker is unable to stay at work or return to work because of an injury or disease”. [1] Work disability is associated with many consequences for the worker, employer, healthcare system and compensation system. [2] There is increasing evidence that health care providers may influence work disability, both positively and negatively. [3] The most prevalent components of clinical return-to-work interventions for musculoskeletal disorders are physical exercises, education and behavioral treatments. [4] These components are considered the core components of return-to-work interventions. [5–9] Unfortunately, early aggressive care may delay recovery [10–14] from whiplash injuries and not listening carefully to the patient (particularly women) may delay return-to-work for occupational low back pain. [15] Unnecessary diagnostic imaging tests are also frequently ordered. [16–20]

It has been demonstrated that general practitioners are less likely to implement evidence-based management of back pain than occupational physicians and occupational therapists. [21, 22] The latter health care providers experience fewer barriers to guideline implementation because their tasks focus on disability prognosis, yellow flag management, and return to activity parameters. [22] However, little is known about the impact of doctors of chiropractic (DCs) on work disability and their adherence to guidelines. Chiropractic and medical care appear to have similar cost-effectiveness during the treatment of occupational low back pain [23, 24] and chiropractic adherence to radiological guidelines appears to be increasing. [25–28] The broad approaches described by DCs experienced in the treatment of occupational injuries are consistent with those proposed by evidence-based guidelines. [29] Barriers related to different provincial workers’ compensation systems have previously been identified by Canadian DCs. [29] It has been hypothesized that DCs that treat a relatively high volume of workers’ compensation cases may have different characteristics than the general chiropractic community. [29] In Quebec, the act regulating occupational injuries grants physicians the role of sole gatekeeper. [30] This is the only province where chiropractic care, to be reimbursed by the provincial workers’ compensation board, must be prescribed by a medical doctor. It is thus reasonable to hypothesize that DCs from the province of Quebec treat fewer workers’ compensation cases on average than DCs from other provinces.

Little is known about the characteristics of health care providers who tend to treat more workers’ compensation cases. Identifying those characteristics is important for understanding the care seeking behaviours of injured workers. This research project aimed to perform a secondary data analysis from a nationwide survey to describe the characteristics of Canadian DCs who tend to treat more workers’ compensation cases.

Specific objective

To identify DCs’ characteristics that are associated with the number of workers’ compensation patients they treat.

Methods

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional analysis using the 2011 survey of the Canadian Chiropractic Resources Databank (CCRD). [31] Members of the Canadian Chiropractic Association (CCA) were surveyed using a self-administered questionnaire (mail or online version). The University of Montreal Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (13-106-CERES-D).

Study Population

Figure 1 The study population included all Canadian DCs who were CCA members and had active practices in 2011. DCs practicing another profession (i.e., dentist, physician, nurse, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, psychologist or radiologist), or not in active practice (i.e., practicing less than 10 hours per week or 37 weeks yearly, retired and semi-retired) were excluded. During the 2011 iteration of the CCRD, 6,533 survey questionnaires were mailed to members of the CCA. The respondents were able to return the paper version of the questionnaire by mail or to complete the survey online. 1,889 questionnaires were returned by mail and 640 were completed online, resulting in a total of 2,529 completed questionnaires. The effective response rate was 38.7 percent. A total of 652 respondents were excluded because they were practicing another profession, not in active practice, or had missing answers for the main dependent variable. The current study included 1,877 respondents (Figure 1).

Source of data

The CCRD survey includes 81 questions detailing the practice and concerns of DCs and is used to inform the Canadian Chiropractic Association about services to provide to their membership. [31] For this project, we used information concerning professional activities, education, research and teaching activities, main sectors of activity, care provided to patients, chiropractic techniques used, type of conditions treated, and referral practices.

Description of study variablesAnnual number of workers’ compensation patients treated by a DC (dependent variable) The annual number of workers’ compensation patients treated by a DC was obtained by multiplying the respondent’s answers to the following questions:

The average number of new patients / week

The average number of weeks practicing chiropractic per year

The percentage of monthly income from the workers’ compensation board.

DC characteristics (independent variables) The survey administered by the CCRD includes multiple items that describe the practice of DCs. The questionnaire contained items classified into five category headings: background information (demographics), professional activity, education, training and affiliations, practice characteristics, finances and income31. Pertinent themes were selected a priori and our hypotheses of the association between selected variables and the number of workers’ compensation cases are listed in Appendix 1.

Analyses

We generated frequencies (categorical variables) or means and standard deviations (continuous variables) for variables that we determined as relevant a priori. To investigate non-responses to the survey, we compared the analyzed sample to the complete CCA membership for all available characteristics (i.e., sex, college of graduation, years of practice and province of exercise) using Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s chi-square test. Bivariate analyses were conducted between all the predetermined independent variables and the annual number of patients referred by MDs using Student’s t-tests and ANOVA for categorical variables and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for continuous variables. When appropriate, the Games-Howell for unequal variances post-hoc test was applied.32 All comparisons were 2-tailed and considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Because our data were highly skewed and over dispersed (i.e., the variance was greater than the mean), a multivariate negative binomial regression was performed to identify factors associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. We did not include the number of new patients per week and the number of weeks of practice per year in our model because they were used to construct the dependent variable. All other independent variables with a P < 0.25 in bivariate analyses were entered into the multivariate negative binomial regression model. The least significant variables were removed from the model individually until all remaining variables had a P < 0.10 to form the preliminary model. We then attempted to reintroduce all the excluded variables individually. The final model was created by reintroducing variables into the model if they had a P < 0.10 or if their introduction altered the other variables’ coefficients by more than 10%.

We reported the incidence rate ratios (IRR) and their 95% confidence intervals for each independent variable included in the final model. The IRR values were obtained from the regression coefficients on an exponential scale. IRR values greater than 1 represent an increase in the annual number of workers’ compensation cases and values lower than 1 represent a decrease. For continuous variables, the IRR represents the average change in the predicted annual number of workers’ compensation patients for a one-unit increase of the independent variable. For categorical variables, the IRR represents the factor of change in the predicted annual number of workers’ compensation patients attributable a given category of the independent variable under examination compared to the reference category. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Mac (version 21.0, IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Figure 2

Table 3

Table 1

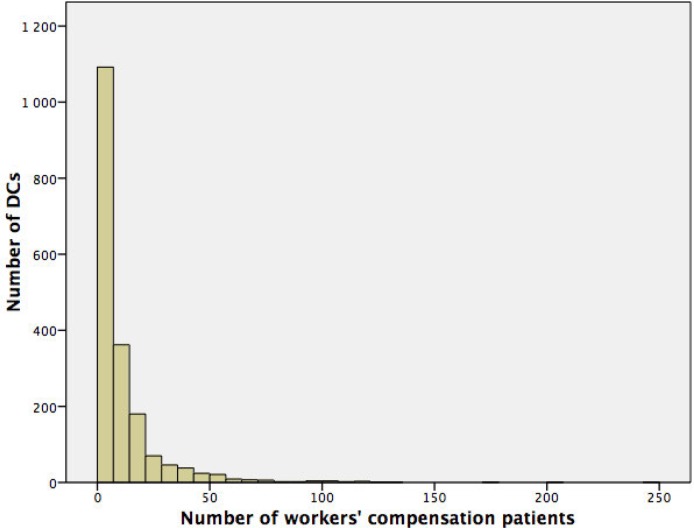

Table 2 On average, DCs received 10.3 (standard deviation (SD) = 17.6) workers’ compensation cases per year. This finding represents 6.2% of all new patients treated by DCs on average in a year. The distribution of the workers’ compensation cases was heavily skewed to the right (Figure 2), with 29.9% of DCs receiving no such cases and 5% receiving more than 40 per year. The results of the bivariate analyses examining the associations between DC characteristics and the number of workers’ compensation cases are presented in Table 3. In this table, the numbers in the second column represent the average number of workers’ compensation patient seen each year and SD for categorical variables and the Pearson’s correlation coefficients for continuous variables.

Representativeness of the current study

The characteristics of the analyzed sample are presented in Table 1. When compared with the complete 2011 membership of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, the analyzed sample had similar distributions in terms of college of graduation, but the analyzed sample included slightly more males (2.9%), included slightly more experienced DCs (1.8 years) and had a significantly different provincial distribution (Table 2).

Association with the number of workers’ compensation casesBivariate results

General information

Male DCs and DCs who perceived that there was an appropriate number of DCs in their area received significantly more workers’ compensation cases. DCs from Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Atlantic provinces received significantly more workers’ compensation cases than DCs from the other provinces. DCs from British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario received significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases than DCs from Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Atlantic provinces, but significantly more cases than DCs from Quebec. DCs practicing in areas of more than 500,000 inhabitants received significantly less workers’ compensation cases than those practicing in areas with populations between 10,000 and 49,999 inhabitants or between 100,000 and 499,999 inhabitants. Age and years of practice were not significantly associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. Post hoc specific comparisons did not reveal significant differences between the types of practice.

Professional activities

The number of hours of practice per week, the number of new patients per week and the number of treatments performed per week were all significantly, positively correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. The number of weeks of practice per year was not significantly correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Education, research and teaching

DCs who had graduated from the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC) received significantly more workers’ compensation cases than those who had graduated from the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR) and Palmer West (PCC-W). The amount of postgraduate education, continuing education, teaching, management training, practice management services, and research activities were not significantly associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Main sectors of activity

DCs reporting occupational/industrial practice, rehabilitation practice, or sports injury management as a main sector of activity received significantly more workers’ compensation cases. DCs reporting maintenance/wellness activities or pediatric care as a main sector of activity received significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases. Reporting that consulting/specialized assessment activities, geriatric care, nutritional activities, or pregnancy care was a main sector of activity was not significantly associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Care provided to patients

DCs that performed their own radiographs received significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases than those who referred their patients to radiology clinics. The percentage of patients who were radiographed was significantly negatively correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. Providing acupuncture, cryotherapy, diathermy, electrotherapy, exercises, heat packs, low volt, soft-tissue therapy, traction, flexion/distraction, ultrasound or patient education was associated with a significantly greater number of workers’ compensation cases. The adjustment practice and providing laser therapy were not significantly associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Chiropractic techniques used

DCs reporting the use of the Diversified technique received significantly more workers’ compensation cases. DCs reporting the use of the Hole-In-One technique received significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases. The uses of the Thompson, Sacro-occipital, Gonstead, Activator or Cranio-Sacral techniques were not associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Types of conditions treated

The reported percentage of patients with neuromusculo-skeletal conditions was significantly positively correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. The reported percentage of patients with somatovisceral conditions was significantly negatively correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. The reported percentage of patients with vascular conditions was not significantly associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Referral practice

The reported percentages of patients referred by their employer or by a physician were significantly positively correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases. The reported percentage of patients referred to other health care providers was not significantly correlated with the number of workers’ compensation cases.

Multivariate results

Table 4 Our final multivariate model (Table 4) included the following: type of clinic; population of practice area; province of practice; number of hours of practice per week; number of treatments per week; post graduate studies; management training; main sector of activity (occupational/ industrial); providing radiographic examination at the clinic; care provided to patients (electrotherapy, soft-tissue therapy); chiropractic technique used (Sacro Occipital technique, Thompson, Cranio-sacral technique); percentage of patients with neuromusculoskeletal conditions; and the percentage of patients referred by their employer or a physician.

All the independent variables of the final model influenced the dependent variable in the same direction as in the bivariate analyses; however, slight changes in their statistical significance were observed. Quebec DCs received significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases than DCs of the other provinces, but the difference from Ontarians was not significant when controlling for all other variables. Sole practitioners received significantly less workers’ compensation cases than DCs practicing with a group of DCs or in a multidisciplinary clinic (without an MD) when controlling for all other variables. Postgraduate studies, management training, and some chiropractic techniques (Sacro Occipital, Thompson and Cranio-sacral techniques) were not significant in the bivariate analyses but became significant in the multivariate model. Providing radiographic examination at the clinic was significantly associated with the number of workers’ compensation cases in the bivariate analyses, but not in the multivariate model.

Discussion

Several of our intuitive a priori hypotheses were not confirmed: age, years of practice, number of DCs in relation to demand, post graduate studies, continued education, adjustment practice, involvement in research and teaching activities were not associated with the reported number of workers’ compensation cases treated per year. CMCC graduates reported more workers’ compensation cases than graduates from UQTR in the bivariate analysis, but the college of graduation was not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. The difference observed in the bivariate analysis was most likely attributable to provincial differences because nearly all UQTR graduates are practicing in Quebec.

The results of our analysis indicate that three broad categories of factors may influence the number of workers’ compensation cases that a DC reports, including the DC’s interactions with other health care providers, a practice oriented toward the treatment of injured workers, and potential access to care.

Interactions with other health care providers

In both our bivariate and multivariate analyses, receiving more physician referrals was associated with a greater number of reported workers’ compensation cases. This is consistent with the results of a previous American study that concluded that physicians were involved in the treatment of the majority of workers receiving care for occupational low back pain. [33] Sending the patient to another clinic for radiologic investigation was associated with a greater number of reported workers’ compensation cases. This association may also indicate better physician-DC collaboration. Working in a multidisciplinary clinic without a physician was also associated with a greater number of reported workers’ compensation cases when controlling for the amount of physician referrals. This result suggests that collaboration with other health care providers is also important during the care of injured workers. This result is supported by the literature, which views inter-professional collaboration as a cornerstone of successful return-to-work. [34–37]

Surprisingly, referring more patients to other health care providers was not associated with the number of reported workers’ compensation cases. This result is may be because in the context of occupational injuries, DCs may receive referral patients that are primarily within their scope of practice. DCs reporting maintenance and wellness care as a main sector of activity reported significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases in all our analyses. This is potentially because they may be perceived as providers of excessive care by other health care providers [38, 39] or by patients who want to rapidly return to work. DCs attending management training reported significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases only when controlling for other variables in the final model. Their marketing strategy may be perceived to be aggressive, which can have a negative impact on physician referrals. [39] DCs interested in developing an occupational practice should develop good inter-professional relationships with physicians and other health care providers.

Practices oriented on the treatment of injured workers It is not surprising that DCs with occupational/industrial and rehabilitation as main sectors of activity report more workers’ compensation cases. Although sports injuries can be similar to occupational injuries, a pediatric-oriented practice is obviously different from an occupational practice. An explanation for the significantly lower number of reported workers’ compensation cases associated with the completion of post graduate studies may be that these DCs specialize in a different field than occupational injury DCs. It is also not surprising that DCs that treat a higher percentage of patients with neuromusculoskeletal conditions report more injured workers because occupational injuries generally lie within their scope of practice. Occupational diseases are not within the scope of chiropractic practice and require medical care.

DCs that treat more injured workers also appear to provide care that respects radiographic guidelines, with less radiographic use associated with an increased number of reported workers’ compensation cases. [27, 28, 40–42] Common components of clinical return-to-work interventions for musculoskeletal disorders4, such as physical exercise and patient education, were also associated with higher numbers of reported workers’ compensation cases. In fact, every additional treatment modality (with the exception of laser therapy) had a significant positive impact on the number of reported workers’ compensation cases in the bivariate analyses. Electrotherapy and soft-tissue therapy met the inclusion criteria for the multivariate model. DCs that offer multimodal care may be perceived as having added value over those that provide only spinal manipulations. Although these results are interesting, clinician DCs should consider the best interests of their patients and remember that spinal traction, laser therapy, electrotherapy and ultrasound are not recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the early management of persistent, non-specific low back pain. [43]

In our bivariate analyses, the Diversified technique had a significant positive impact on the number of reported workers’ compensation cases while the Hole In One technique had a significant negative impact. In our multivariate analysis, the Thompson technique had a significant positive impact on the number of workers’ compensation cases reported while Sacral Occipital Technique had a significant negative impact when controlling for all other variables. The Hole in One technique is a spinal manipulative technique specializing in the upper cervical area. Because cervical injury is only one type of occupational injury, this may explain why DCs using this technique report fewer workers’ compensation cases. Additionally, DCs using the Thompson and Sacral Occipital techniques may provide different care to workers’ compensation patients or patients may differently seek care from DCs that use these techniques. Further investigations will be necessary to understand the impact of chiropractic techniques on care seeking behaviors.

DCs that report more workers’ compensation cases also report more employer referrals. This observation is interesting because an American study revealed that employers selected the majority of providers for workers who receive care. [33] Employers were more likely to choose physicians, while workers were more likely than employers to select DCs. [33]

Our results suggest that DCs that consider occupational/industrial care as a primary sector of activity, stimulate employer referrals and offer care adapted to the needs of injured workers (multimodal care, avoiding excessive radiographic imaging); therefore, these DCs tend to report more workers’ compensation cases.

Potential access to care

In both our bivariate and multivariate analyses, the practice area population, practice province and number of practicing hours per week were significantly associated with the reported number of workers’ compensation cases. The number of practicing hours per week as well as practicing in a group of DCs (compared with solo practice) increases the number of hours when injured workers are able to seek care. Our results indicate that DCs in larger cities (more than 500,000 inhabitants) report less workers’ compensation cases. Usually, Canadians in rural areas experience more difficulty when seeking immediate care. [44] A possible explanation for these results may be that injured workers in smaller towns have access to a limited number of providers and seek more care from their local DCs, while the opposite situation is present in metropolitan centers.

When DCs perceive that there is an appropriate number of DCs in their area, they report significantly more workers’ compensation cases than when they perceive that there are too many DCs, which also supports the previous hypothesis. As expected, Quebecers report significantly fewer workers’ compensation cases than DCs from the other provinces in all our analyses. Physicians, the sole gatekeepers to the Quebec worker’s compensation system30, are acting as a barrier to chiropractic care. In general, the residents of eastern Canadian provinces are more likely to report difficulty accessing routine and immediate care than residents of western provinces44. This may explain why DCs in the Atlantic provinces receive the highest number of workers’ compensation cases. Our results suggest that DCs offering more office hours and practicing in areas with limited access to other health care resources report more workers’ compensation cases.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is the large sample size, which provides sufficient statistical power for modeling all the investigated DC characteristics. The use of an appropriate regression model (negative binomial) also enabled us to deal with the highly skewed distribution of the annual number of workers’ compensation cases.

Our results obtained from the secondary analysis of the CCRD cross-sectional survey should be interpreted with caution. As with every cross-sectional study, the temporality of the exposure-outcome relationship cannot be firmly established. A prospective study would provide better evidence regarding the temporality of the observed associations between the different independent variables and the amount of workers’ compensation board cases. The low response rate, 38.7%, has important implications. It is possible that non-responders may have systematically differed from responders and that our results may have limited the generalizability to DCs outside of the analyzed group. Additionally, the proportion of respondents differed between the provinces. The DCs in our analysis had an average 1.8 years more practice experience and were 2.9% more often males than the complete CCA membership. Although these differences are relatively small, they are significant and may have biased the magnitude of the observed associations.

It is also possible that DCs that chose to be CCA members have different profiles than non-members. However, in order to reverse the direction of the observed associations, the non-respondents would need to show an inverse relationship between the dependent and the independents variables. The CCRD survey was not designed for the purpose of this study and the metric properties of the questionnaire are unknown. Our composite dependent variable might not reflect the exact number of workers’ compensation case seen by DCs. Furthermore, our model only included data available in the CCRD and it is possible that other variables, such as the incidence of occupational injuries in the area of practice, may be of interest.

Nonetheless, we believe our results provide valuable information regarding DC characteristics associated with the amount of workers’ compensation cases. Additional qualitative research would be useful to better identify the relevant factors that influence the type of care sought by injured workers and to understand the mechanism underlying the choice of healthcare provider.

Conclusion

The reported number of workers’ compensation cases substantially varies among Canadian DCs, with nearly one-third of DCs’ receiving no cases and a few DCs receiving many cases. Canadian DCs with practices oriented toward the treatment of injured workers that collaborate with other health care providers and facilitate workers’ access to care reported more workers’ compensation patients.

Appendix 1.

List of a priori hypotheses regarding the association between relevant CCRD variables and the number of workers’ compensation patients seen per year

Funding support:

Dr. Blanchette is supported by a PhD fellowship from CIHR. This work was supported by the Work Disability Prevention Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategic Training Program Grant (FRN: 53909).

References:

Loisel P, Anema JR.

Handbook of Work Disability. Prevention and management.

Springer; 2013.Loisel P, Buchbinder R, Hazard R, et al.

Prevention of work disability due to musculoskeletal disorders: the challenge of implementing evidence.

J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):507–524.Carel Hulshof M, Pransky G.

Handbook of Work Disability. Springer; 2013.

The Role and Influence of Care Providers on Work Disability; pp. 203–215.Staal JB, Hlobil H, van Tulder MW, Koke AJ, Smid T, van Mechelen W.

Return-to-work interventions for low back pain: a descriptive review of contents and concepts of working mechanisms.

Sports Med. 2002;32(4):251–267.Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al.

Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD002014Oesch P, Kool J, Hagen KB, Bachmann S.

Effectiveness of exercise on work disability in patients with non-acute non-specific low back pain:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(3):193–205.Hagen EM, Eriksen HR, Ursin H.

Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain?

Spine. 2000;25(15):1973–1976.Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O.

Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial.

Spine. 1995;20(4):473–477.Costa-Black KM.

Handbook of Work Disability. Springer; 2013.

Core Components of Return-to-Work Interventions; pp. 427–440.Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C.

Initial patterns of clinical care and recovery from whiplash injuries: a population-based cohort study.

Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2257–2263.Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C.

Early aggressive care and delayed recovery from whiplash: isolated finding or reproducible result?

Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):861–868.Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P, Frank J.

Does multidisciplinary rehabilitation benefit whiplash recovery?:

results of a population-based incidence cohort study.

Spine. 2007;32(1):126–131.Pape E, Hagen KB, Brox JI, Natvig B, Schirmer H.

Early multidisciplinary evaluation and advice was ineffective for whiplash-associated disorders.

Eur J Pain. 2009;13(10):1068–1075.Scholten-Peeters GG, Neeleman-van der Steen CW, van der Windt DA, Hendriks EJ, Verhagen AP, Oostendorp RA.

Education by general practitioners or education and exercises by physiotherapists for patients

with whiplash-associated disorders? A randomized clinical trial.

Spine. 2006;31(7):723–731.Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Fremont P, et al.

Determinants of “return to work in good health” among workers with back pain who consult

in primary care settings: a 2-year prospective study.

Eur Spine J. 2007;16(5):641–655Loisel P, Durand M-J, Berthelette D, et al.

Disability prevention:new paradigm for the management of occupational back pain.

Pract Dis Management. 2001;9(7):351–360.Bussieres AE, Peterson C, Taylor JA.

Diagnostic Imaging Practice Guielines for Musculoskeletal Complaints in Adults —

An Evidence-Based Approach: Introduction

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Nov); 30 (9): 617–683Bussieres AE, Peterson C, Taylor JA.

Diagnostic Imaging Practice Guidelines for Musculoskeletal Complaints in Adults —

An Evidence-Based Approach: Part 2: Upper Extremity Disorders

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jan); 31 (1): 2–32Bussieres AE, Taylor JA, Peterson C.

Diagnostic Imaging Practice Guidelines for Musculoskeletal Complaints in Adults —

An Evidence-Based Approach: Part 1: Lower Extremity Disorders

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Nov); 30 (9): 684–717Bussieres AE, Taylor JA, Peterson C.

Diagnostic Imaging Practice Guidelines for Musculoskeletal Complaints in Adults —

An Evidence-Based Approach: Part 3: Spinal Disorders

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jan); 31 (1): 33–88Webster BS, Courtney TK, Huang YH, Matz S, Christiani DC.

Survey of acute low back pain management by specialty group and practice experience.

J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(7):723–732.Poitras S, Durand MJ, Cote AM, Tousignant M.

Guidelines on low back pain disability: interprofessional comparison of use between

general practitioners, occupational therapists, and physiotherapists.

Spine. 2012;37(14):1252–1259.Baldwin ML, Cote P, Frank JW, et al.

Cost-effectiveness Studies of Medical and Chiropractic Care for

Occupational Low Back Pain. A Critical Review of the Literature

Spine J. 2001 (Mar); 1 (2): 138–147Brown A, Angus D, Chen S, et al.

Costs and outcomes of chiropractic treatment for low back pain (Structured abstract)

Health Technology Assessment Database. 2005;(2):88.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clhta/articles/HTA-32005000361/frame.htmlBussieres AE, Patey AM, Francis JJ, et al.

Identifying factors likely to influence compliance with diagnostic imaging guideline recommendations

for spine disorders among chiropractors in North America: a focus group study using the theoretical domains framework.

Implement Sci. 2012;7:82Bussieres AE, Laurencelle L, Peterson C.

Diagnostic imaging guidelines implementation study for spinal disorders:

a randomized trial with postal follow-ups.

J Chiropr Educ. 2010;24(1):2–18.Ammendolia C, Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C.

Do Chiropractors Adhere to Guidelines for Back Radiographs?

A Study of Chiropractic Teaching Clinics in Canada.

Spine 2007 (Oct 15); 32 (22): 2509-2514Ammendolia C, Taylor JA, Pennick V, Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C.

Adherence to radiography guidelines for low back pain: a survey of chiropractic schools worldwide.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):412–418.Cote P, Clarke J, Deguire S, Frank JW, Yassi A.

Chiropractors and return-to-work: the experiences of three Canadian focus groups.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(5):309–316.Gouvernement du Québec .

In: Loi sur les accidents du travail et les maladies professionnelles (LATMP) Québec, editor.

Québec :QC: Éditeur officiel du Québec; 1985.

Vol L.R.Q., c. A-3.001.Kopansky-Giles D, Papadopoulos C.

Canadian chiropractic resources databank (CCRD): a profile of Canadian chiropractors.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1997;41(3):155–191.Games PA, Howell JF.

Pairwise multiple comparison procedures with unequal n’s and/or variances: a Monte Carlo study.

J Education Behav Stat. 1976;1(2):113–125Cote P, Baldwin ML, Johnson WG.

Early patterns of care for occupational back pain.

Spine. 2005;30(5):581–587.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, van Tulder M, et al.

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for subacute low back pain among working age adults.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):Cd002193.Loisel P, Durand MJ, Baril R, Gervais J, Falardeau M.

Interorganizational collaboration in occupational rehabilitation: perceptions

of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation team.

Journal Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):581–590.Loisel P, Falardeau M, Baril R, et al.

The values underlying team decision-making in work rehabilitation for musculoskeletal disorders.

Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(10):561–569.Brunarski D, Shaw L, Doupe L.

Moving toward virtual interdisciplinary teams and a multi-stakeholder approach in

community-based return-to-work care.

Work. 2008;30(3):329–336.Busse JW, Jim J, Jacobs C, et al.

Attitudes towards chiropractic: an analysis of written comments from a survey of north american orthopaedic surgeons.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2011;19(1):25.Busse JW, Jacobs C, Ngo T, et al.

Attitudes toward chiropractic: a survey of North American orthopedic surgeons.

Spine. 2009;34(25):2818–2825.Ammendolia C, Bombardier C, Hogg-Johnson S, Glazier R.

Views on radiography use for patients with acute low back pain among chiropractors in an Ontario community.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(8):511–520.Ammendolia C, Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C.

Utilization and costs of lumbar and full spine radiography by Ontario chiropractors from 1994 to 2001.

Spine J. 2009;9(7):556–563.Ammendolia C, Hogg-Johnson S, Pennick V, Glazier R, Bombardier C.

Implementing evidence-based guidelines for radiography in acute low back pain:

a pilot study in a chiropractic community.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(3):170–179.Savigny P, Watson P, Underwood M.

Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain: summary of NICE guidance.

BMJ. 2009;338:b1805.Sanmartin C, Ross N.

Experiencing difficulties accessing first-contact health services in Canada:

Canadians without regular doctors and recent immigrants have difficulties accessing

first-contact healthcare services. Reports of difficulties in accessing care vary by age, sex and region.

Healthcare Policy. 2006;1(2):103–119

Return to WORKERS' COMPENSATION

Since 12-18-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |